Depletion of groundwater is accelerating in California's Central Valley, study finds

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Academic

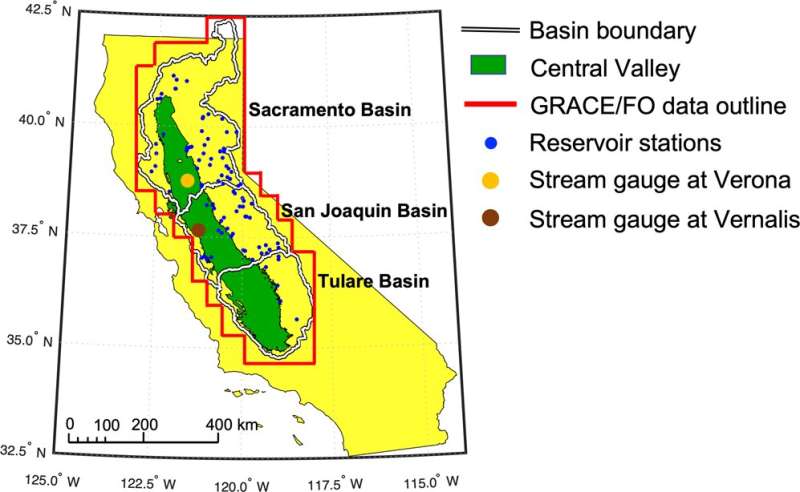

California's Central Valley. The Central Valley (green) encompasses the Sacramento, San Joaquin, and Tulare Basins (black and white boundary). The red border outlines the area of GRACE/FO mascon data used for the study. Blue dots show locations of active reservoir storage gauges distributed within the study region, and the orange and brown dots show locations of the two main stream discharge gauges in Central Valley. The GRACE/FO data, reservoir storage and streamflow measurements are used to estimate groundwater storage changes as discussed in the Methods section. Credit: Nature Communications (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-35582-x

Scientists have discovered that the pace of groundwater depletion in California's Central Valley has accelerated dramatically during the drought as heavy agricultural pumping has drawn down aquifer levels to new lows and now threatens to devastate the underground water reserves.

The research shows that chronic declines in groundwater levels, which have plagued the Central Valley for decades, have worsened significantly in recent years, with particularly rapid declines occurring since 2019.

"We have a full-on crisis," said Jay Famiglietti, a hydrology professor and executive director of the University of Saskatchewan's Global Institute for Water Security. "California's groundwater, and groundwater across the southwestern U.S., is disappearing much faster than most people realize."

Famiglietti and other scientists found in their study, which was published this month in the journal Nature Communications , that since 2019, the rate of groundwater depletion has been 31% greater than during the last two droughts.

They also found that groundwater losses in the Central Valley since 2003 have totaled approximately 36 million acre-feet, or about 1.3 times the full water-storing capacity of Lake Mead near Las Vegas, the country's largest reservoir.

"The trajectory we're on right now is one for 100% disappearance," Famiglietti said. "This is the water for the future generations. And it's disappearing."

California's historic Sustainable Groundwater Management Act was passed in 2014 with the intent of curbing overpumping and stabilizing aquifer levels. But the law, known as SGMA, gives many local agencies until 2040 to achieve sustainability goals.

Famiglietti said the findings indicate that timeline may be far too long, pointing to a need to speed up implementation of regulation under the law. The current pace of groundwater losses is now nearly five times faster than the long-term average since the 1960s.

"We are seeing what appears to be a rush to pump as much groundwater as possible before new restrictions take hold," Famiglietti said. "My fear is that by the time SGMA is fully implemented, it will be too late. There will be nothing left to manage."

The rush on groundwater comes amid the driest three-year period ever recorded in California, as well as a larger megadrought worsened by global warming that has blanketed the American Southwest for 23 years.

SEE RESEARCH PAPER ATTACHED

Media

Taxonomy

- Groundwater

- Groundwater Recharge

- Groundwater Assessment

- Groundwater Modeling

- Groundwater Pollution

- Groundwater Mapping

- Surface-Groundwater Interaction

- Groundwater Quality & Quantity

- Groundwater Resource

- Public Water System and Groundwater Issues

- Central Ground Water Board

- Groundwater Surveys and Development

- Groundwater monitoring and assessments

- Groundwater Remediation

- Groundwater Data Scientist