Permafrost Loss Changes Yukon River Chemistry

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Academic

Permafrost loss due to a rapidly warming Alaska is leading to significant changes in the freshwater chemistry and hydrology of Alaska's Yukon River Basin with potential global climate implications.

A scientist standing in front of an ice-rich permafrost exposure on the coast of Herschel Island, Yukon Territory (photo: Michael Fritz).

This is the first time a Yukon River study has been able to use long-term continuous water chemistry data to document hydrological changes over such an enormous geographic area and long time span.

The results of the study have global climate change implications because of the cascading effects of such dramatic chemical changes on freshwater, oceanic and high-latitude ecosystems, the carbon cycle and the rural communities that depend on fish and wildlife in Alaska's iconic Yukon River Basin. The study was led by researcher Ryan Toohey of the Department of the Interior's Alaska Climate Science Center and published in Geophysical Research Letters.

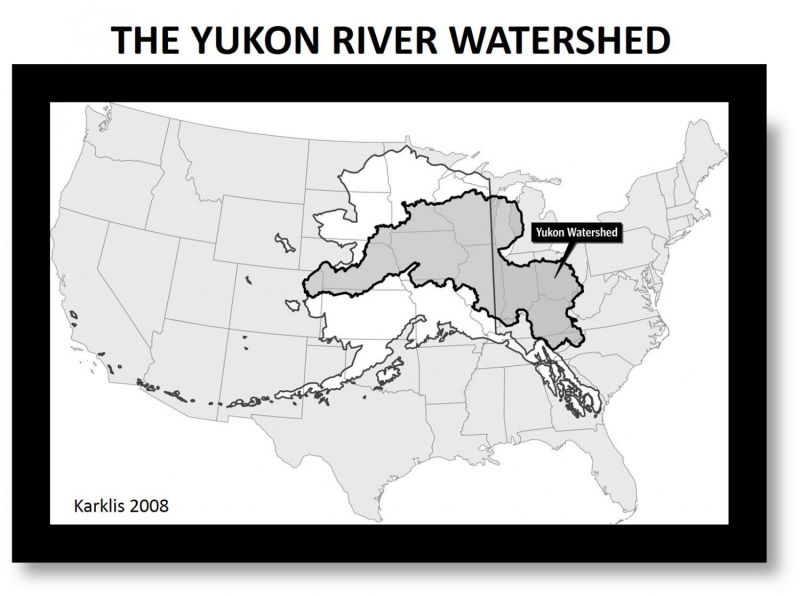

The Yukon River Watershed is immense, as evidenced here when it is superimposed over a map of the continental U.S. Credit: Laris Karklis

Permafrost rests below much of the surface of the Yukon River Basin, a silent store of thousands of years of frozen water, minerals, nutrients and contaminants. Above the permafrost is the 'active layer' of soil that freezes and thaws each year. Aquatic ecosystems -- and their plants and animals -- depend on the ebb and flow of water through this active layer and its specific chemical composition of minerals and nutrients.

When permafrost thaws, the soil's active layer expands and new pathways open for water to flow through different parts of the soil, bedrock and groundwater. These new pathways ultimately change the chemical composition of both surface water and groundwater.

"As the climate gets warmer," said Toohey, "the thawing permafrost not only enables the release of more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, but our study shows that it also allows much more mineral-laden and nutrient-rich water to be transported to rivers, groundwater and eventually the Arctic Ocean. Changes to the chemistry of the Arctic Ocean could lead to changes in currents and weather patterns worldwide."

Another recent study by University of Alberta scientist Suzanne Tank documented similar changes on another major Arctic river, the Mackenzie River in Canada. With two of these rivers showing striking, long-term changes in their water chemistry, Toohey noted that "these trends strongly suggest that permafrost loss is leading to massive changes in hydrology within the arctic and boreal forest that may have consequences for the carbon cycle, fish and wildlife habitat and other ecosystem services."

Source: Eurek Alert

Media

Taxonomy

- River Studies

- Climate Change

- River Engineering

- Hydrology

- Groundwater Resource

- Climate Risk

- Ecosystem