Cholera Map- From satellite to smartphone, app warns public of unsafe water

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Technology

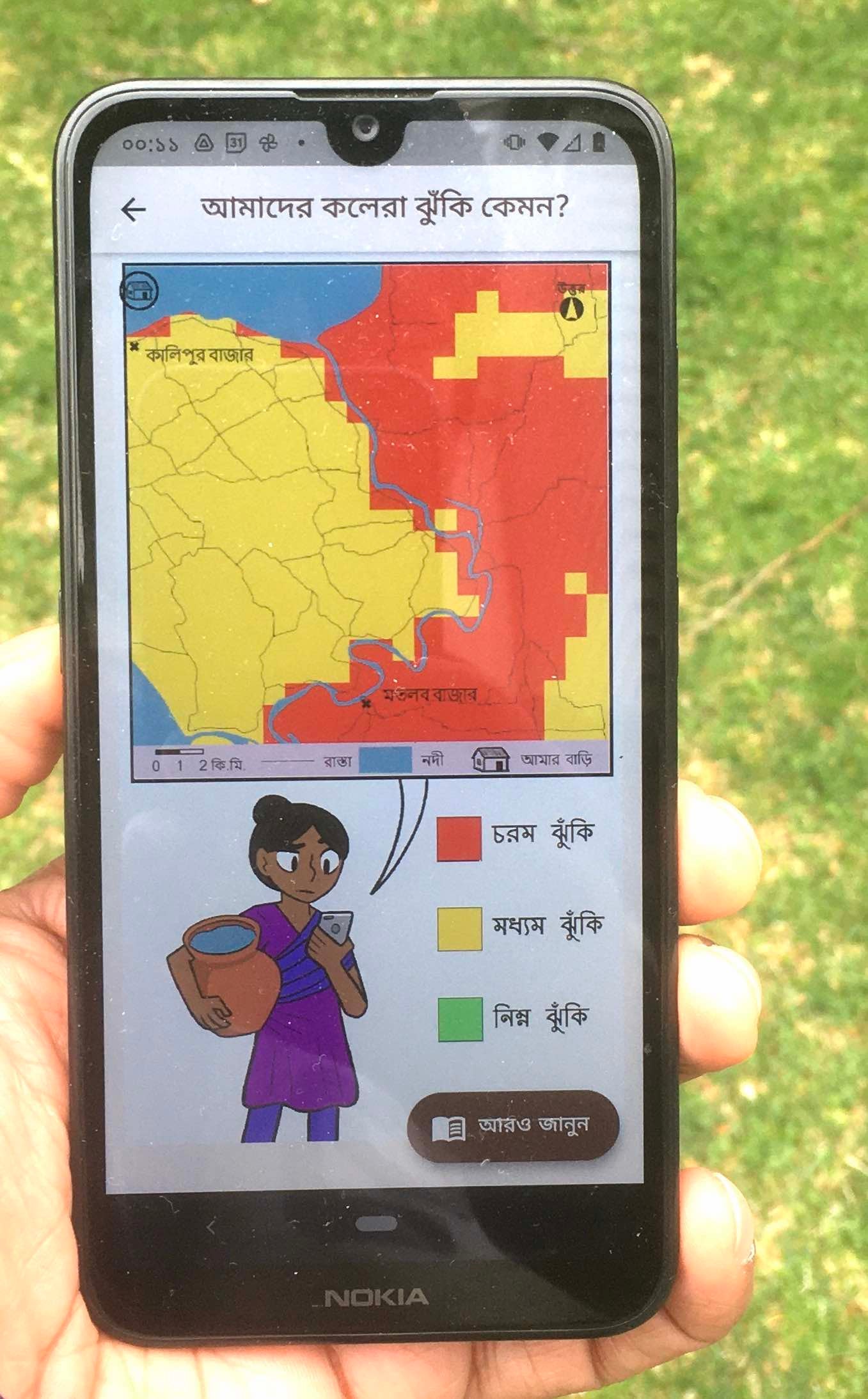

The color-coded CholeraMap app appears in Bangla. It can easily be translated into other languages for other regions. (Photo courtesy of Ali Shafqat Akanda)

App creates early-warning risk maps based on environmental conditions

KINGSTON, R.I. – July 8, 2021 – Each year, there are 1.3 to 4 million cases of cholera worldwide, causing upwards of 140,000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization.

In developed countries, such as the United States, people don’t generally have to worry about their water causing cholera, an acute diarrheal infection induced by drinking water that is contaminated with bacteria. But in developing nations in Asia and Africa, safe water is not guaranteed, and cholera remains a major threat to public health.

Due to changing climatic conditions and recurrent natural disasters in the Bengal Delta area of Bangladesh, the population is especially susceptible to persistent cholera and seasonal fluctuations of the disease throughout the year.

With that most vulnerable population in mind, University of Rhode Island Professor Ali Shafqat Akanda and a team of researchers have developed an application for smartphones called CholeraMap to serve as an early warning device for cholera.

CholeraMap creates early-warning risk maps based on environmental conditions derived from NASA satellite observations. The risks are communicated to the smartphones of villagers in Bangladesh, who had input in the design of the app.

Taking an interdisciplinary approach

Akanda, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, has been collaborating on the project with researchers from other majors at URI and those from other universities.

The team at URI has spearheaded the development of the app. Working with Akanda has been Akanda’s doctoral student Farah Nusrat; Abdeltawab Hendawi, a computer science professor; and Abdullah Islam, a computer science doctoral student.

The lead investigator on the project is Sonia Aziz, associate professor of economics at Moravian College in Pennsylvania. Other researchers on the project include Emily Pakhtigian, assistant professor of public policy at Pennsylvania State University; and Kevin Boyle, a professor of agricultural and applied economics at Virginia Tech University.

From published papers to practice

Akanda has been studying the link between cholera and the changes in the climate and the water environment since he was a doctoral student at Tufts University, working with Professor Shafiqul Islam, director of the Water Diplomacy program.

The idea of using data from satellite images to track cholera was introduced to Akanda by his mentor, Professor Rita Colwell, of the University of Maryland.

Since graduating from Tufts in 2011, cholera has been a subject Akanda has been passionate about. With dozens of articles published in some of the highest-rated journals in the field, Akanda is considered an expert on the subject. By developing the app, Akanda is hopeful that his knowledge of cholera can be used to reach those who are at the greatest risk.

“When you write a paper, you hope many people will read it, but often it just sits in a journal,” said Akanda. “My motivation for working on the app is to actually transfer the research into application and practice in order to make a difference in the lives of people living in vulnerable countries.”

How the app works

Designed for people living in villages that are most in danger of getting cholera, the app provides three important pieces of information:

- The app displays a color-coded map where the cholera “hotspots” are located based on environmental data monitored by satellites, such as water scarcity, the temperature of the air and ground, and rainfall extremes

- The hotspots are categorized as low, medium or high, indicating how careful residents should be

- Recommendations are also provided on how to stay safe based on the risk levels, such as boiling water before use, not swimming or fishing in bodies of water, and not rinsing fruits and vegetables with water that may be high in bacteria

The aquatic ecosystem in Bangladesh has been susceptible to persistent cholera. (Photo courtesy of Ali Shafqat Akanda)

Implementing the project

Developers of the app plan a year-long trial by users in Bangladesh. To implement the study, there needs to be enough people with access to the technology.

As it turns out, there are communities in the targeted area that don’t have infrastructure in place for traditional communication, such as good roads connecting landlines, but rapid development of mobile connectivity has allowed people even in those regions to gain access to cell phones.

“There’s been a huge increase in smartphone penetration in recent years because the prices of both handsets and data services have come way down,” said Akanda.

Identifying people to test the app and educating the public on the purpose of the study has taken a grassroots effort in Bangladesh.

One of the world’s leading global health research institutes, the International Centre for Diarrhoel Disease Research, Bangladesh, known as icddr,b, based in Dhaka, has collaborated on the project by helping to line up 1,500 people to participate in the trial. The app was developed in Bangla, the native language of the region.

During the course of the study, a comparison will be made between those using the app and those not using it. Some of the metrics that will be tracked and analyzed are cholera-related hospital visits, water-usage behavior of the people in high-risk areas, the cost of treatment and lost productivity due to bouts of diarrheal disease and hospital visits.

A ‘labor of love’

For Akanda, this project has personal significance. Having grown up in Bangladesh, he and his family were all too familiar with the dangers of contaminated water.

“My father grew up in a region that was very prone to cholera,” said Akanda. “He told me stories of times when his family had to flee the village when cholera outbreaks would occur later in the year, in October and November. When they returned to the village, once the water was safe again, they found that many of the people who stayed had succumbed to the disease.”

Akanda himself fell victim to cholera while visiting Bangladesh in 2016.

“I ate some fruits from street vendors, which was not washed properly and showed that the danger is still very present,” said Akanda. “The population there, especially the poor, is very vulnerable because they don’t have access to clean water or the knowledge of the danger and how to avoid it.”

Expanding the scope

In time, the app could be implemented in other parts of the world where cholera has become a serious health risk. However, according to Akanda, the learning curve about the infection could be a greater challenge than implementing the technology.

“Cholera is a growing problem in parts of Africa, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Cameroon, but the transfer of knowledge to areas not familiar with cholera is not easy,” said Akanda.

Because Bangladesh has a much longer history with cholera, the public has learned how to combat the infection with oral rehydration solutions.

“In the first 24 to 48 hours of contracting cholera, people are most likely to die from dehydration from the high frequency of diarrhea,” said Akanda. “The shops and pharmacies sell rehydration solutions, so people in Bangladesh know where to find it in a hurry or how to make it.”

The project is funded by the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization Resources for the Future under the aegis of the Valuables consortium, a collaboration with NASA to measure how satellite information benefits people and the environment.

Taxonomy

- Environmental Health

- Public Health