India’s rural-urban conundrum: Get smart to revitalise rural regions

Published on by Dr. Cecilia Tortajada, Professor in Practice, School of Interdisciplinary Studies, University of Glasgow, UK

Asit K Biswas, Udisha Saklani and Cecilia Tortajada

Asit K Biswas, Udisha Saklani and Cecilia Tortajada

POLICY FORUM | October 9, 2017

Indians are flocking to the country’s megacities in huge numbers. More needs to be done to provide them with opportunities and livelihoods in the country’s rural areas, Asit K Biswas, Udisha Saklani and Cecilia Tortajada write.

Recently India’s beleaguered cities have been the subject of intense scrutiny and criticism. This year’s monsoon rains have caused many deaths and widespread economic and social disruptions. In Bihar, more than 500 people have lost their lives. In neighbouring Uttar Pradesh, more than 100 people died and some 3,000 villages were submerged. In Gujarat, another 213 people died and around 130,000 people had to be relocated to safer grounds. Bustling metropolises like Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Bengaluru came to a halt. All these cities are overcrowded and suffer from flawed urban planning that intensifies loss of life due to any natural disaster.

Mumbai, one of the most seriously affected megacities and the financial capital of India, is home to more than 21 million people. That residential population is expected to rise to 42 million by 2030. This provides little scope for restoring its green cover, wetlands and floodplains that are crucial for flood control, as China is doing for its sponge cities.

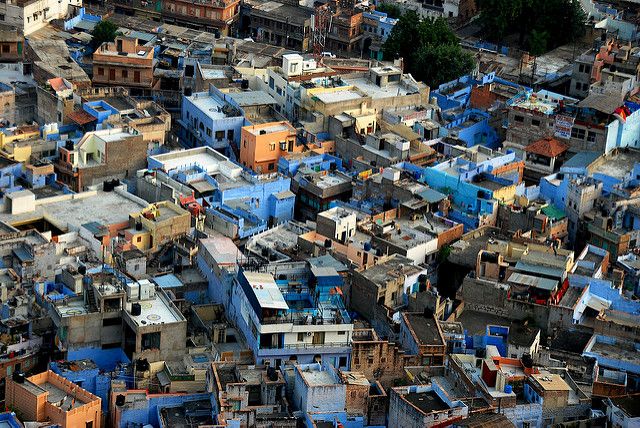

India’s expanding cities such as Delhi or Mumbai are ill-prepared to handle the growing population and to provide a reasonably decent quality of life. Liveability across most cities has steadily declined as municipal governments struggle to manage rapid urbanisation and the rising expectations of residents. Without the formulation and implementation of good long-term urban planning, ad-hoc and haphazard infrastructure developments have ensured these cities are simply unable to cope with natural disasters of even moderate scales.

More and more Indians are migrating to urban centres in search of better incomes, education and livelihoods. With 410 million urban dwellers, India now has the second largest urban population in the world, after China.

According to the UN, an additional 404 million people will be added to India’s urban population by 2050. Migrants get absorbed in sectors such as construction and services that require unskilled or semi-skilled labour. However, many of these jobs are disappearing and will continue to disappear due to mechanisation, extensive use of robots and advances in artificial intelligence.

To cope with its growing population, India needs to generate one million jobs each month for at least the next 30 years. By 2050, India’s working population will have more than 1 billion people between the age of 15 and 64. Cities are already challenged by inadequate and dilapidated infrastructure that cannot meet current needs let alone demanding future requirements. If adequate employment opportunities cannot be created for such a large population, there is likely to be increasing social unrest. Furthermore, rising inequalities in income and opportunities will play havoc with social fabrics of cities.

The typical governance response to this growing urban challenge has been to direct funding towards city-centric development plans aimed at redesigning and upgrading existing facilities. For instance, under the Smart Cities initiative, the Central and State governments will allocate a whopping Rs. 960 billion (AU $18.9 billion) over five years for pilot programmes in 100 cities. The competitively chosen cities will also benefit from other infrastructure programmes such as the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) scheme, further channelling additional funds to them.

Redevelopment of Indian cities has been the top priority for successive governments for decades. However, such measures are not enough to reduce uncontrolled rural-to-urban migration that further pressures an overburdened civic infrastructure, increases pollution and environmental degradation, and steadily decreases the quality of life for urban dwellers.

While significant emphasis is given to redevelopment of large cities, there are few successful initiatives designed to make villages self-sustaining.

In the past, national rural redevelopment schemes such as Providing Urban Amenities to Rural Areas (PURA) had very limited success. Improvements in infrastructure and development in villages remain conspicuous by their absence. The rigour, analysis and publicity given to urban redevelopment plans such as the Smart City scheme are not available to rural redevelopment initiatives.

As a result, the rural exodus is on the rise and cities continue to bear the brunt of sprawling urban slums due to unhindered migration.

In the face of rising urban challenges exacerbated by the risk of environmental hazards, India needs a new path of development that will ensure sustainable livelihoods for rural people while reducing rural-urban migration and thus creating a positive impact on cities.

After the latest floods, the Gujarat government announced a plan to rehabilitate 15 low-lying villages from Patan and Banaskantha districts that are prone to frequent flooding. The plan is modelled on a similar initiative undertaken after the 2001 Gujarat earthquake that destroyed many villages. Such initiatives present a good opportunity to develop model villages that can align priorities to redeveloping rural areas into smart and sustainable villages and reduce rural-urban migration.

An important priority should be on building strong civic and social infrastructure currently lacking in large parts of rural India. The relocated villages should be well-connected through transportation and communication networks to other parts of the country. They should be planned so that all of them have access to electricity, clean water and adequate sanitation and wastewater treatment facilities. If such villages can be consolidated into small clusters, they could also have good access to medical and education facilities, as well as recreational and entertainment alternatives for young people.

In addition to having good civic amenities, the resettled population should have employment opportunities which could be provided by public and private sectors. These could incentivise youth to stay in rural areas and have options for sustainable livelihoods, including starting small business ventures after receiving proper training. An holistic ecosystem aimed at generating sustainable livelihoods could dissuade small farmers, traders and traditional artisans from migrating to big cities in pursuit of low-paying subsistence jobs.

Building self-reliant and sustainable villages that offer a decent standard of living will go a long way in positively impacting both the rural and urban diaspora. If properly planned and executed, such small villages can be a roadmap for rural development in India.

Recent debates have revolved around decentralising development by building new urban villages to slow down the rapid urbanisation of big cities. Natural hazards like the recent floods serve as a reminder that Indian cities are heavily overpopulated, poorly managed and often lack basic infrastructure.

Attention should now focus on accelerating growth and development processes of rural India. Until and unless India ensures living in rural areas could provide people with a decent standard of living and quality of life, it is difficult to see how India can manage an estimated 1.76 billion people by 2050.

Asit K Biswas is the Distinguished Visiting Professor, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. National University of Singapore, Singapore. Udisha Saklani is an independent policy researcher working in association with the Institute of Water Policy, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore. Cecilia Tortajada is a senior research fellow at the Institute of Water Policy, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore .

Source: http://bit.ly/2kBGgWT

Media

Taxonomy

- India