NFIP Must Be Improved: 5 Ways to Promote Climate Resilience

Published on by Rachel Cleetus, Lead Economist and Climate Policy Manager at Union of Concerned Scientists in Academic

If you own a home along the coast or elsewhere in a floodplain, you may have heard of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). What you may not know is that this program doesn’t just provide insurance; it is also critical for how we assess risks and help protect people and property in flood-prone areas.

The NFIP is up for Congressional re-authorization in September 2017, and it’s time to consider changes that would make the program work better, especially in light of growing development in floodplains and climate change.

Projections of sea level rise and increased heavy downpours should be a sobering check to where and how we build, rebuild, and protect our homes and valuable long-lived infrastructure.

Photos of the building boom along the Miami coastline and other coastal flood-prone areas are a reminder that we’re doing things that just don’t make sense given what we know about sea level rise.

One powerful way to effect change: Fix and harness the market incentives created by the national flood insurance program.

What is the National Flood Insurance Program?

The NFIP is the primary source of flood insurance for homes and small businesses—standard home insurance policies do not cover this risk.

The program has three main components: flood insurance, flood risk mapping, and floodplain management. Created by Congress in 1968, it is administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). At the time the program was set up, it was recognized that the private market would find it difficult to provide affordable, widely-available flood insurance coverage. Also, policymakers understood that integrating floodplain management with an insurance program would be the most effective way to reduce risk.

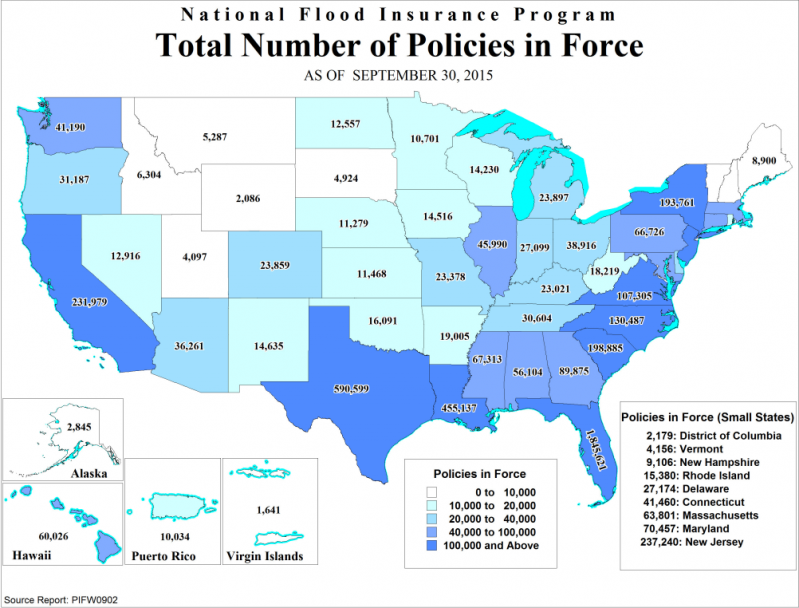

Source: FEMA

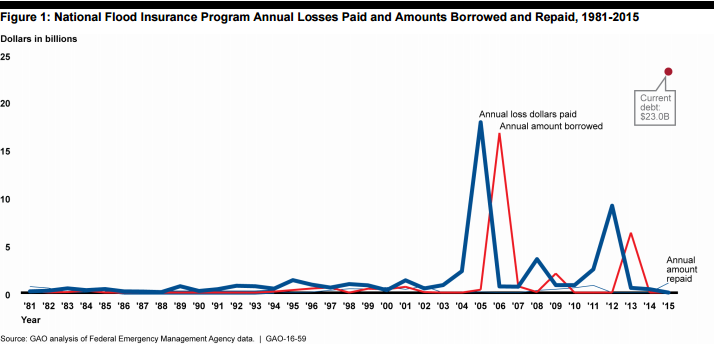

Today the program has over five million policyholders, with Florida, Texas, Louisiana, California, and New Jersey leading in terms of number of policies. The program is over $23 billion in debt, primarily due to the impacts of Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, and has been on the GAO’s High-Risk list for the last ten years.

While the NFIP is a very valuable program for millions of people, it has some well-understood shortcomings that can perpetuate risky development in floodplains.

Subsidized premiums, outdated flood maps, and not enough resources or options to help people lower their flood risks, all contribute to costly and potentially dangerous outcomes.

With development continuing to grow along our coasts and other floodplains, and sea level rise and heavy downpours increasing due to climate change, it’s time to fix the NFIP so it can continue to serve us well over the long term.

Recent attempts at reforming the program—the 2012 Biggert-Waters Act (BWA) and the 2014 Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act (HFIAA)—have failed to adequately address the underlying problems. The upcoming reauthorization process gives us a fresh opportunity to review the NFIP and make common-sense changes that will better safeguard people and property, limit taxpayer liability, and ensure that a robust NFIP continues to help people insure their homes for decades to come.

Five ways to improve the National Flood Insurance Program

Here are five things Congress should include in legislation as it reauthorizes the NFIP:

1. Update flood risk maps to reflect the latest science , including projections of sea level rise and increased precipitation that can worsen flood risks.

Currently, these maps only show the projected flood risk based on current conditions and modeling of past storms and flooding. With climate change, the past is not a good predictor of the future. In addition to serving as the basis for setting NFIP insurance rates, FEMA’s flood risk maps (also known as Flood Insurance Rate Maps or FIRMs) are also the primary source of information for federal, state, and local government planners and private developers, utilities, and other infrastructure builders to help them determine the risk of flooding for their projects.

FEMA should update its flood risk maps based on the recommendations of the Technical Mapping Advisory Council (TMAC). Drawing up new maps is costly so we also need Congress to authorize adequate funding for the National Flood Mapping Program to complete science-based flood mapping for every community.

2. Phase in risk-based pricing and broaden the insurance base. NFIP’s history of subsidized premiums has created fiscal difficulties for the program, and it’s meant that homeowners don’t always have a true understanding of the risks for which they need to prepare.

It’s important to note that the NFIP’s mission of providing widely-available, affordable flood insurance makes it different from private insurance, with a rate structure that is not designed to be actuarially sound in the aggregate. However, major storms and now climate change will continue to put fiscal pressure on the program unless the rate structure is adjusted. Congress should phase in NFIP rate increases to reflect updated risk assessments in the floodplain, while taking other measures to address equity concerns (see #3).

In some cases FEMA simply lacks the information needed to improve rate-setting and needs time and money to address that. Homeowners in high-risk areas should be required to maintain flood insurance coverage since studies show that many drop coverage after a few years. The program should also create incentives for homeowners outside the highest risk areas (the Special Flood Hazard Area or SFHA where insurance is mandatory) to buy insurance, since FEMA estimates that over 20 percent of NFIP claims come from areas outside the designated SFHA.

3. Address equity considerations for low and moderate income households. Increased flood insurance premiums can be challenging for low- and moderate-income households.

The NFIP should include affordability provisions based on the recommendations of the NAS, including rebates, tax credits, and means-tested vouchers coupled with hazard mitigation loans or grants. The program should also encourage more communities to take advantage of the Community Rating System, which provides flood insurance discounts for communities that invest in flood mitigation measures.

4. Provide more resources for homeowners and communities to cope with flood risks. People in flood-prone areas need more resources to help them reduce their flood risks, including through elevation of homes, community-wide efforts such as maintaining floodplain open space, and other flood-proofing investments.

The Flood Mitigation Assistance Program’s funding of $199 million in FY16 is not nearly enough. In the highest risk areas where sea level rise may lead to repeated flooding or inundation within decades, people need more options and resources (such as voluntary buyout programs), so that they can make better choices about their future.

For example, in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, FEMA worked with local and state governments in New Jersey and New York to initiate property acquisition programs. Capacity-building and technical assistance are also needed to help homeowners and communities assess and implement options to mitigate flood risks, including in high-rise public housing and other types of multi-family buildings. The $3 billion in federal funding for the New York City Housing Authority to repair and protect public housing developments damaged by Sandy provides one such example.

5. Ensure that private sector flood insurance complements the NFIP without undermining it. There is increased interest in a private market for flood insurance (See, for example, H.R. 2901 the Flood Insurance Market Parity and Modernization Act).

A robust private market may be beneficial and should appropriately be encouraged, but care must be taken that this does not undermine our nation’s efforts to provide affordable, widely-available flood insurance and build resilience in an equitable way. Congress must ensure a system where a strong NFIP continues to be a viable option, alongside private sector flood insurance.

The NFIP should not be left holding the highest risk policies while private insurers take on the more profitable end of the market. Unlike private insurers, the NFIP is required by law to accept all applicants as long as they are in a participating community—this means that the program already has a higher exposure to losses. Private flood insurance providers must also share in the costs of flood mapping and floodplain management efforts, which are critical to keeping risks and costs down for everyone.

Other experts have also recently shared recommendations for how to improve our nation’s flood insurance policies, including the Association of State Floodplain Managers, researchers at the Wharton Risk Center, Resources for the Future research on a proposed design for community flood insurance, and the Government Accountability Office.

FEMA has also indicated that it is continuing to work on many past recommendations it has received from the GAO and others. One important need: improving transparency and accountability for the private companies that write NFIP policies.

Change may be hard… but it is necessary

Reforming the NFIP is not going to be easy. While it’s primarily about insurance, it’s also about people’s homes and their ability to continue to afford to live in places that they love and may have lived in for generations.Unfortunately, climate change is making some of those places increasingly risky places to be.

Of course, it’s not enough to simply raise insurance rates. We’ve got to limit flood risks in a more thoughtful, comprehensive way, including through better mapping and more investments in flood mitigation. Insurance is just one tool in our toolbox. We also need more planning and resources so all communities can protect themselves or move out of harm’s way. Low-income coastal communities, like those in Atlantic City or Plaquemines Parish, should not be left in the lurch.

The last time Congress grappled with NFIP reform, there was a great deal of concern and anger from some communities regarding new flood maps and increased premiums. In some cases there was a lack of information or misinformation. Legislation at the time did not properly address equity considerations. Some maps were based on outdated or inaccurate data, a problem caused in no small part because of the fact that Congress has woefully underfunded flood mapping for decades. (In 2016, funding for mapping was restored to $312 million, after cuts in a number of recent years).

Clearly, any future changes to the NFIP must be made in a transparent, science-based way, recognizing equity concerns, and with an opportunity for stakeholder engagement. Phasing in changes can help make the adjustments easier. Adequate funds must also be made available to properly implement the necessary changes. Issues like appropriate rate-setting are complex and fraught but we can take significant steps in the right direction. Congress punted on taking serious action last time; hopefully, policymakers will show some leadership and that won’t happen again next year.

A recent report from Zillow found that, with 6 feet of sea level rise by the end of the century,

“Nationwide, almost 1.9 million homes (or roughly 2 percent of all U.S. homes) – worth a combined $882 billion – are at risk of being underwater by 2100…More than 1 in 8 properties in Florida are in an area expected to be underwater if sea levels rise by six feet”

That’s the reality we have to face up to: Climate change is increasing flood risks in places that millions of Americans call home; let’s make sure our policies are set up to protect people instead of burying our heads in the sand.

Originally posted at UCSASA

Media

Taxonomy

- Flood Management

- Climate Change

- Climate Change Resilience

- Flood management

- Flood prediction

- Flood Risk Management

- Flood Insurance

- Climate