Abandoned Urban Spaces to Fight Climate Change

Published on by Dusko Balenovic, Previous Network Manager at The Water Network in Technology

Local Code takes thousands of underused urban spaces and optimizes them to fight flooding, heat, and extreme weather.

City infrastructure—like sewer pipes, for instance—are built to accommodate a certain number of people, and withstand a certain amount of bad weather. But with climate change heralding higher temperatures and larger storms and more unexpected weather events, American cities' 19th century infrastructure will only be resilient up to a point.

City infrastructure—like sewer pipes, for instance—are built to accommodate a certain number of people, and withstand a certain amount of bad weather. But with climate change heralding higher temperatures and larger storms and more unexpected weather events, American cities' 19th century infrastructure will only be resilient up to a point.

But what if you could create a network of sites across a city, that together could mitigate particular ecological threats, from sudden storm waters to heat waves?

What if you could use a computer program to create thousands of site-specific designs for abandoned land in that city, maximizing its positive ecological impact?

What if you could use a computer program to create thousands of site-specific designs for abandoned land in that city, maximizing its positive ecological impact?

That's what Nicholas de Monchaux has done. The UC Berkeley professor of urban design and architecture has spent the last six years working on a project called Local Code.

He has mapped thousands of underused sites in four different cities—starting with San Francisco, followed by Los Angeles, New York, and Venice, Italy—and has written code to connect each specific location with a design proposal to transform it into a point of urban resilience.

The proposals would fill these abandoned sites with greenery, bioswales, porous paving, and low albedo surfaces—all established techniques for increasing urban resilience and improving the ecology of a city.

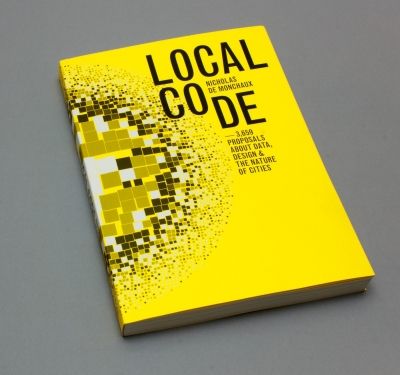

In October, his findings—in the form of 3,659 individual, site-specific design proposals and several complementary essays—were published in the book Local Code by the Princeton Architectural Press.

But getting to this point took six years of work, combing through cities for underutilized spaces below billboards, in alleys, and in vacant lots. Here's how he did it.

CODING RESILIENCE

After mapping thousands of abandoned sites, de Monchaux's next step was to design the best infrastructural and ecological use for each. And the most effective way to do that was to connect his GIS mapping software and parametric design software.

But there weren't any design tools out there that could stand up to the task—so with the help of the Berkeley Center for New Media (of which he is the director) and a residency program at the software company Autodesk, de Monchaux wrote his own.

He calls it a "software pipeline" between the two existing programs. "It’s the same as any design problem, but your design intelligence is being spread in a completely new way across many different sites," he says.

The open-source software, now available for anyone to use on Github, takes a set of parameters—like the amount of stormwater, the material and condition of the surrounding buildings, the location of nearest sewer pipe and how much it can handle—and spits out a site-specific design for the space.

Using the program, de Monchaux can test the effects of different kinds of designs on the dataset. "Instead of saying we’re going to put green things anywhere, we’re using the power of digital design tools to actually place individual elements on each site where they can do the most ecological good," he says.

For instance, it doesn't make sense to install materials that absorb solar radiation where the sun rarely shines. De Monchaux's tool instead figures out where the sun shines on every single site and where the most solar radiation hits over the course of a year. Those then become the ideal location for loams and plants.

Another example: The software can build a flow model of storm water, tracking where the water comes from and where it goes, as well as where the existing storm sewer is located. Then, it recommends that a stormwater retention device like a bioswale be placed between the source and destination, slowing down the water as it moves towards the sewer system.

It took six years for de Monchaux to develop the code that would support the program's many, many different parameters and situations. And even so, the design relationships don't work for 5% of the sites. But the bigger challenge? Any of these designs are only starting points for conversations within the local communities. The software, of course, doesn't take in account social or political factors, mostly because those are difficult to model.

"You couldn’t maximum design for social impact, but you can for the flow of water," he says. Instead, Local Code attempts to show how much can be accomplished with this new kind of framework, using the power of data and computers.

Read full article at: Fast Co Design

Media

Taxonomy

- Technology

- Smart City

- Environment

- Infrastructure

- Sustainability

- Urban Design

- Software Solutions

- Software

1 Comment

-

innovative