Rethinking Water Management Issues

Published on by Asit Biswas, Distinguished Professor at University of Glasgow in Government

NITI Aayog’s strategy for water resources is a continuation of failed policies of the past.

By Chetan Pandit and Asit K. Biswas, THE HINDU | October 9, 2019

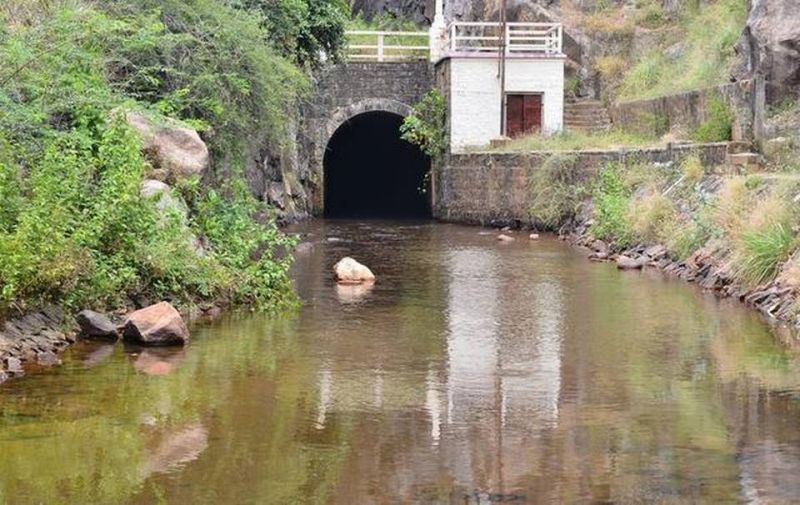

Image source: The Hindu

NITI Aayog’s strategy for water resources is a continuation of failed policies of the past.

Chetan Pandit and Asit K. Biswas

THE HINDU | October 9, 2019

In December 2018, NITI Aayog released its ‘Strategy for New India @75’ which defined clear objectives for 2022-23, with an overview of 41 distinct areas. In this document, however, the strategy for ‘ water resources’ is as insipid and unrealistic as the successive National Water Policies (NWP). Effective strategic planning must satisfy three essential requirements. One, acknowledge and analyse past failures; two, suggest realistic and implementable goals; and three, stipulate who will do what, and within what time frame. The ‘strategy’ for water fails on all three counts.

NO NEW VISION

The document reiterates two failed ideas: adopting an integrated river basin management approach, and setting up of river basin organisations (RBOs) for major basins. The integrated management concept has been around for 70 years, but not even one moderate size basin has been managed thus anywhere in the world. And 32 years after the NWP of 1987 recommended RBOs, not a single one has been established for any major basin.

The water resources regulatory authority is another failed idea. Maharashtra established a water resources regulatory authority in 2005. But far from an improvement in managing resources, water management in Maharashtra has gone from bad to worse. Without analysing why the WRA already established has failed, the recommendation to establish water resources regulatory authorities is inexcusable.

The strategy document notes that there is a huge gap between irrigation potential created and utilised, and recommends that the Water Ministry draw up an action plan to complete command area development (CAD) works to reduce the gap. Again, a recommendation is made without analysing why CAD works remain incomplete, that too despite having a CAD authority as an integral component of the ministry.

Goals include providing adequate and safe piped water supply to all citizens and livestock; providing irrigation to all farms; providing water to industries; ensuring continuous and clean flow in the “Ganga and other rivers along with their tributaries”, i.e. in all Indian rivers; assuring long-term sustainability of groundwater; safeguarding proper operation and maintenance of water infrastructure; utilising surface water resources to the full potential of 690 billion cubic metres; improving on-farm water-use efficiency; and ensuring zero discharge of untreated effluents from industrial units. These goals are not just over ambitious, but absurdly unrealistic, particularly for a five-year window. Not even one of these goals has been achieved in any State in the past 72 years. Some goals, such as ‘Har Khet Ko Pani (irrigation to every field)’, are simply not achievable.

WHO IS ACCOUNTABLE?

A strategy document must specify who will be responsible and accountable for achieving the specific goals, and in what time-frame. Otherwise, no one will accept the responsibility to carry out various tasks, and nothing will get done. Take one goal: “Encourage industries to utilise recycled/treated water”. Merely encouraging someone to do something, is not a “goal”. That apart, NITI Aayog does not say who will do this encouraging, and how? Should the State Water Ministries do this by restricting or even withholding recalcitrant industry’s access to fresh water? Should the Environment Ministries cancel clearances for industries which do not practise recycling? Or should the Finance Ministries do this through monetary incentives and disincentives? No one knows.

Of the issues listed under ‘constraints’, only one, the Easement Act, 1882, which grants groundwater ownership rights to landowners, and has resulted in uncontrolled extractions of groundwater, is actually a constraint. The remaining are are not constraints. These are: irrigation potential created but not being used; poor efficiency of irrigation systems; indiscriminate use of water in agriculture; poor implementation and maintenance of projects; cropping patterns not aligned to agroclimatic zones; subsidised pricing of water; citizens not getting piped water supply; and contamination of groundwater. These are problems, caused by 72 years of mis-governance in the water sector, and remain challenges for the future.

Ideas listed under ‘way forward’ and ‘suggested reforms’ do not say how any of these will come about. For example, there is no recommendation to amend the Easement Act, or to stop subsidised/free electricity to farmers. On the contrary, the strategy recommends promoting solar pumps. These are environmentally correct and ease the financial burden on electricity supply agencies. However, the free electricity provided by solar units will further encourage unrestricted pumping of groundwater, and will further aggravate the problem of a steady decline of groundwater levels.

REFORMS OVERLOOKED

The document fails to identify real constraints. For example, it notes that the Ken-Betwa River inter-linking project, the India-Nepal Pancheshwar project, and the Siang project in Northeast India need to be completed. A major roadblock in completion of these projects is public interest litigations filed in the National Green Tribunal, the Supreme Court, or in various High Courts. Unless the government has a plan to arrest the blatant misuse of PIL for environmental posturing, not only these but also other infrastructure projects will remain bogged down in court rooms.

The document takes no cognisance of some real and effective reforms that were once put into motion but later got stalled, such as a National Water Framework law; significant amendments to the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act; and the Dam Safety Bill.

India’s water problems can be solved with existing knowledge, technology and available funds. But India’s water establishment needs to admit that the strategy pursued so far has not worked. Only then can a realistic vision emerge. It is unfortunate that NITI Aayog has failed to admit this and has prescribed only a continuation of past failed policies. Far from solving our water problems, this helps India to continue walking on the unsustainable path it has pursued for decades.

Chetan Pandit is a former member of the Central Water Commission. Asit K. Biswas is Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Glasgow, U.K., and Chairman, Water Management International Pte Ltd, Singapore.

This article was published by THE HINDU, October 9, 2019.

Media

Taxonomy

- Public Health

- Treatment

- Policy

- Technology

- Research

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Water Supply

- Infrastructure

- Governance & Planning

- India