Climate Change: A Threat and an Opportunity for WASH

Published on by Minja Ivanov, REC Bulgaria in Academic

Climate change and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) are inseparable. The persistent separation of climate policy making and WASH service delivery, combined with incoherent climate finance strategies, risks restricting progress for both.

In a cluttered and confusing climate change policy landscape, there are two crucial things to remember:

Climate change is water change, and it affects poor people most, especially those without access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).

Although it's a threat to global WASH access, climate change also represents a huge opportunity, if we play our cards right. Increasing political attention, growing climate finance, and a long-overdue focus on the threats to sustainable WASH services offer us new mechanisms to help achieve the target of universal access by 2030.

Fortunately, the UN annual climate talks taking place in Marrakech over the next two weeks now turn to the implementation of the historic Paris Agreement signed in December 2015. The Agreement came into force on 4 November 2016, so the time to face the multitude of critical decisions required to turn this Agreement into meaningful action is now.

Bridging the gap between WASH and climate change

Bridging the gap between WASH and climate change

Far too many decision-makers currently overlook the fact that WASH and climate change are inseparable.

On the one hand, floods spread disease when there are no toilets, longer droughts mean people (usually women) have to walk even further to collect water, and rising seas make groundwater too salty to drink.

On the other hand, having access to a clean and reliable water supply and somewhere safe to go to the toilet is fundamental to building climate resilience.

What these interlinkages mean in practice is that all future development needs to be sustainable and resilient to climate change. And all climate change activity – including both mitigation and adaptation – must take into account the impact on water resources and, by extension, the water security of individuals and communities.

For this to happen we urgently need to dispel any doubt that WASH and climate change are so intimately linked that they must be tackled together, because the current twin track approach is limiting the effectiveness of both communities.

At a global level, this divide plays out by the Sustainable Development Goals and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change being quite separate entities – separate people going to separate meetings developing separate policies.

At the national level, interaction between the ministry that develops climate policy and spends climate funds and the ministries that oversee WASH is often poor or non-existent. This can be compounded by development partners – such as UN agencies, development banks, and NGOs – that also have their own separate climate and water divisions.

At all levels, from global to local, we need to identify the key junctures where the WASH and climate communities come together to share information and make joint decisions. WASH sector strategies, climate adaptation plans, and carbon emissions reduction strategies will all have more effective and equitable outcomes if both the climate and WASH communities are genuinely engaged throughout the process.

Capitalising on climate finance for climate-resilient WASH

Although the tricky issue of ‘who pays for what’ will always have the potential to frustrate delicate negotiations, if approached intelligently, climate financing can be an incentive to drive the joint development and climate actions that are needed to achieve universal access and build climate resilience.

First, high-quality, climate-resilient WASH programmes must be central to the climate adaptation plans of all countries that have large numbers of people living without access to WASH (and are therefore highly vulnerable to climatic changes). In many cases this will require better integration of the development and climate agendas. We in the WASH sector can do more to ensure the links between WASH and increased resilience are better understood.

Second, we should be wary of an over-reliance on the private sector to meet the $100bn per year goal that was agreed in Copenhagen in 2009. Yes, innovative sources (such as climate bonds) are absolutely essential to meeting joint climate and development goals. However, concessional public finance will continue to be needed in areas where private finance is unlikely to flow. There is little profit incentive in meeting the adaptation needs of poor and remote communities – and public money must prioritise these areas.

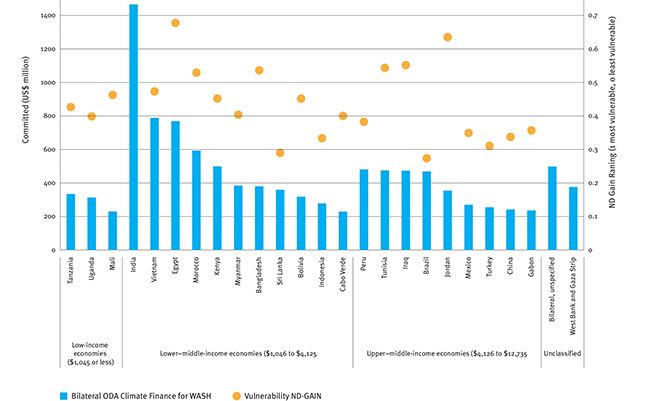

Third, climate finance must be more equitably allocated. Currently less than a third of all climate finance reaches the least developed countries that need it most.1 In the WASH sector, WaterAid research shows that it is middle-income countries that have benefitted most from climate spending (India, Vietnam and Egypt). New mechanisms must be put in place to ensure allocations are made on assessment of climate vulnerability and need, not on a ‘first come first served’ basis that unfairly benefits countries able to develop fundable project pipelines. This will often require investments to support climate finance readiness and ensuring the systems are in place to sustain development and adaptation benefits.

No time to waste

Above all, we need to act fast. Climate change is no longer a future threat – it is happening here and now. The Paris Agreement was a huge step, and developing countries have been ambitious in their climate plans – we must now play our part by developing a fair and efficient system to help them finance this ambition.

Written by Louise Whiting, a WaterAid’s Senior Policy Analyst – Water Security & Climate Change.

Source: WaterAid

Media

Taxonomy

- Sanitation

- Climate Change

- Water & Sanitation

- Sanitation & Hygiene

- Sanitation & Hygiene

- Sanitation Awareness

- Climate Change

- Water Sanitation & Hygiene (WASH)

- Climate

1 Comment

-

Great appreciation about the need to joint WASH and Climate Change-related policy efforts. WaterAid has a big advocacy mission to do in this regard.