A new solution for cleaning up PFAS

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Academic

A solution for cleaning up PFAS, one of the world's most intractable pollutants

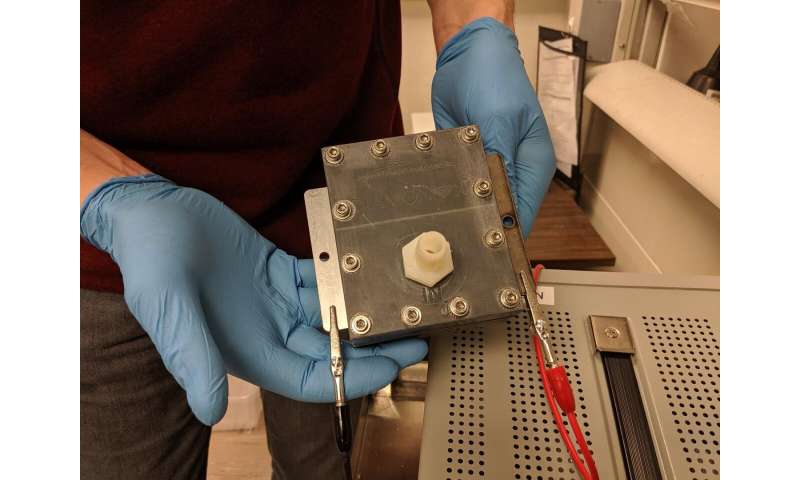

An electrochemical flow cell with a stainless steel cathode and a boron-doped diamond anode is used to treat a concentrated waste stream of GenX. Credit: Colorado State University

A cluster of industrial chemicals known by the shorthand term "PFAS" has infiltrated the far reaches of our planet with significance that scientists are only beginning to understand.

PFAS—Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances—are human-made fluorine compounds that have given us nonstick coatings, polishes, waxes, cleaning products and firefighting foams used at airports and military bases. They are in consumer goods like carpets, wall paint, popcorn bags and water-repellant shoes, and they are essential in the aerospace, automotive, telecommunications, data storage, electronic and healthcare industries.

The carbon-fluorine chemical bond, among nature's strongest, is the reason behind the wild success of these chemicals, as well as the immense environmental challenges they have caused since the 1940s. PFAS residues have been found in some of the most pristine water sources, and in the tissue of polar bears. Science and industry are called upon to clean up these persistent chemicals, a few of which, in certain quantities, have been linked to adverse health effects for humans and animals.

Among those solving this enormously difficult problem are engineers in the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering at Colorado State University. CSU is one of a limited number of institutions with the expertise and sophisticated instrumentation to study PFAS by teasing out their presence in unimaginably trace amounts.

Now, CSU engineers led by Jens Blotevogel, research assistant professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, have published a new set of experiments tackling a particular PFAS compound called hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid, better known by its trade name, GenX. The chemical, and other polymerization processes that use similar chemistries, have been in use for about a decade. They were developed as a replacement for legacy PFAS chemicals known as "C8" compounds that were—and still are—particularly persistent in water and soil, and very difficult to clean up (hence their nickname, "forever chemicals").

GenX has become a household name in the Cape Fear basin area of North Carolina, where it was discovered in the local drinking water a few years ago. The responsible company, Chemours, has committed to reducing fluorinated organic chemicals in local air emissions by 99.99%, and air and water emissions from its global operations by at least 99% by 2030. For the last several years, Chemours has also funded Blotevogel's team at CSU as they test innovative methods that would help the environment as well as assist the company's legacy cleanup obligations.

Media

Taxonomy

- PFAS