Colorado Groundwater Quality and Emerging Contaminants

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Academic

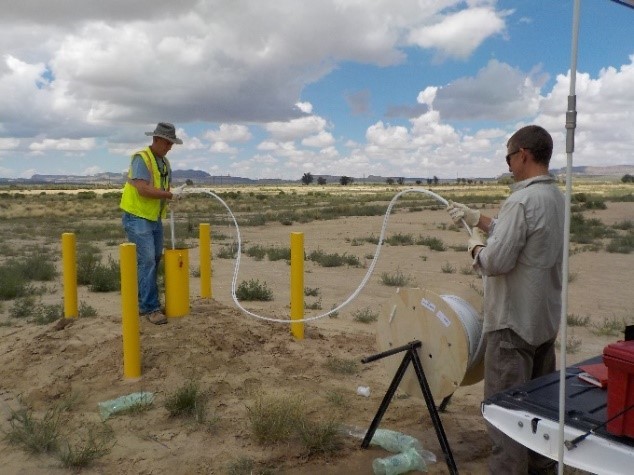

INTERA staff collecting water samples from a groundwater well for contaminant testing and remediation.

Groundwater is an important resource that Coloradans have relied on for more than a century. There are over a quarter million wells in the State and four out of five of them are small domestic household wells. Statewide, the Colorado Geological Survey estimates that 20 percent of Coloradans depend on groundwater. Agriculture is the largest user of groundwater, accounting for 86 percent. As the state has grown, surface water and groundwater resources have been strained both in the quantity and quality.

Figure 1. A map of deep aquifers in the Denver Groundwater Basin. Source: Colorado Division of Water Resources.

By its nature, groundwater presents unique challenges and opportunities. Groundwater is found in aquifers, which are underground reservoirs composed of geologic material permeable enough to yield water from wells and springs. The water in aquifers has accumulated over time and can be replenished slowly, which limits the amount that can be sustainably pumped. An important advantage of groundwater is that it can be less affected by drought than surface water from rivers and streams. Aquifers can provide a “reservoir” to store surplus supplies in wet years for later use in dry years. This is conjunctive use management. There is growing interest in aquifer storage and recovery (ASR), a type of conjunctive use, where surplus supplies are injected by wells into the underlying aquifer for later withdrawal when the water is needed. The practice of ASR and other strategic conjunctive uses of surface water and groundwater are important components of the Colorado Water Plan and central to the water supply strategies of many water utilities. Because of the critical role of groundwater aquifers in Colorado’s future, protection and management of groundwater quality is very important. Once groundwater contamination occurs, it is very difficult and expensive to clean up. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Some contaminants are naturally present in groundwater. However, many groundwater contaminants result from human activities that produce chemicals or wastes. The most common groundwater contaminants in Colorado are nitrate, fluoride, selenium, iron, manganese, radium, and uranium. Figure 2 shows common sources of man-made contaminants. Examples include septic systems, direct disposal of hazardous waste into ground, landfills, spills or leakage from chemical material storage tanks or ponds, leakage from military and weapon manufacturing sites, leakage from sewage pipelines, agricultural pesticides and fertilizers, waste from active or abandoned mining facilities and waste migration from ground surface to the groundwater through poorly constructed wells.

Figure 2. Source: M.E. Gharamti. 2014. Data Assimilation for Management of Industrial Groundwater Contamination at a Regional Scale. Semantic Scholar.

Naturally occurring contaminants originate from the soils and geology of the aquifer and vary significantly by location and depth. Such contaminants include decaying organic matter, iron, manganese, arsenic, chlorides, fluorides, sulfates and radionuclides. The degree to which these substances contaminate groundwater depends on the local geology and geochemistry. Figure 2 shows extent of deep groundwater aquifers in Colorado.

Understanding and characterizing aquifers and groundwater contamination enables utilities to manage risks to their water supply wells. Strategic monitoring, testing, and groundwater modeling can enable utilities to better understand and characterize the contamination. This information can then be used to design and implement remediation, mitigation, and source protection efforts. Such efforts can protect the public water supply while minimizing the financial impact of groundwater contamination on communities.

The Rocky Mountain Arsenal and Rocky Flats Superfund sites are two contaminated groundwater sites that have received a lot of publicity in Colorado. The cleanup of the Rocky Mountain Arsenal, a previous chemical manufacturing facility contaminated by over 600 chemicals, was completed in 2010. The cleanup of the Rocky Flats site, a previous nuclear weapon manufacturing facility, was completed in the early 2000s.

Recently, a group of thousands of chemicals known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been receiving increased attention. A very small portion of these are currently detectable with today’s technology. These chemicals are used in firefighting foam, many industrial processes and consumer products such as Teflon and Scotchguard. The compounds may be found in surface water and groundwater near airports, certain manufacturing facilities, landfills, and in treated effluent and residuals from wastewater treatment plants. Concentrations of these chemicals have been detected above the health advisory levels in multiple places in Colorado including Buckley Air Force Base in Denver, Sugar Loaf Fire Station in west Boulder, the Suncor refinery in north metro Denver, near Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado Springs, Security/Widefield near Colorado Springs and City of Fountain in El Paso County. According to Colorado state officials, more than 100,000 residents have relied on public drinking water systems with elevated PFAS levels in source wells. Colorado approved an action plan in 2019 which includes a series of actions to address PFAS contamination. Such actions include monitoring, surveys of fire departments, controls on the use of firefighting foam at airports, increased State capacity for testing PFAS in water and support for small utilities.

Recently, Colorado decided to enact state laws to regulate PFAS in wastewater discharges. Under Colorado’s current regulations, five of the PFAS constituents are regulated, specifying limits at the point of discharge to lakes and streams. Entities that discharge water such as manufacturing facilities, wastewater treatment plants and other entities are now required to monitor PFAS. These entities are also required to test levels of 25 predefined PFAS constituents in the discharge water and report results to the State. If results show elevated levels above the respective threshold, the entity is required to lower the contaminant below the regulated thresholds.

Treating and removing PFAS can place a financial burden on utilities. As PFAS and other new emerging contaminants of concern arise, efforts will be needed to better understand the treatment and financial implications. Innovative techniques can be employed to minimize contaminants in pumped groundwater. Such efforts will require a thorough understanding and characterization of the extent of contamination and of underlying aquifers. Groundwater data collection coupled with groundwater modeling can be very useful in meeting this objective and in selecting the most feasible treatment option(s).

Learn more about water contaminants in our Citizen’s Guide to Water Quality Protection and read about groundwater in our recently published Citizen’s Guide to Colorado Groundwater.

Taxonomy

- Education Institute

- Education & Research

- Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM)