The EU's water crisis by the numbers

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Social

The EU's water crisis by the numbers

Brussels says it wants to save Europe’s waters. Here's what it's up against.

By GIOVANNA COI

Illustration by Long Yan for POLITICO

This article is part of the Europe’s looming water crisis special report.

The European Commission’s long-awaited Water Resilience Strategy, set to come out in June, aims to “make Europe water-resilient” by improving the quality and management of the bloc’s waters and protecting it against the consequences of climate change.

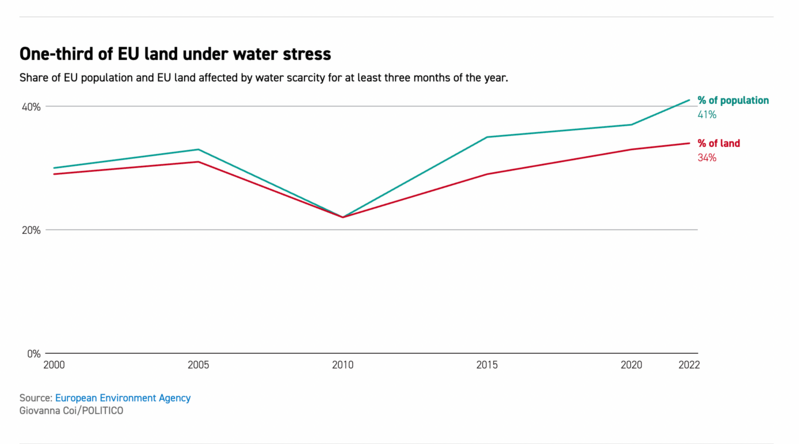

But solving Europe’s water crisis is no easy feat. More than 40 percent of the EU’s population is already experiencing water scarcity — and data shows that without swift action, more and more people will lose unfettered access to this essential resource.

According to the European Environment Agency’s freshwater chief Trine Christiansen, the EU is facing “serious challenges to water security, both today and in the future” and “we simply may not have enough water of good enough quality for the many purposes we would like to use it for.”

A 2024 report from the EEA concluded that Europe’s water resources are under growing pressure from pollution and overuse. It also highlighted that climate change will make water access and management more challenging, causing loss of life and billions in economic damage.

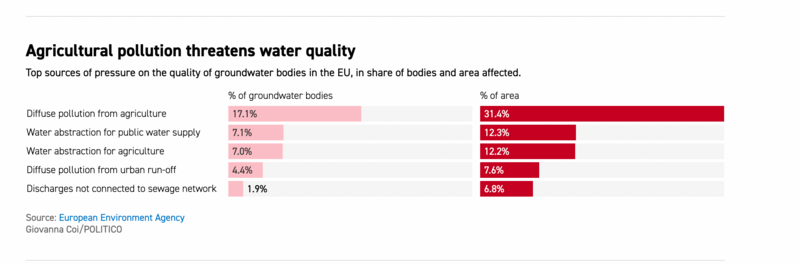

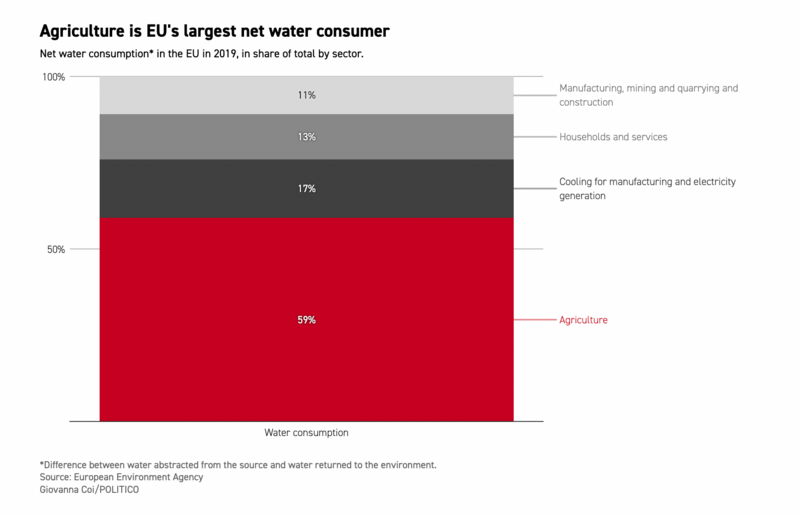

The EEA concluded that “major changes” to Europe’s lifestyles and economic system are the only solution to the continent’s deepening water crisis. The agency identified agriculture as a major culprit, being both the biggest net user of water and the top polluter. The sector accounted for almost 60 percent of the EU’s net freshwater consumption according to the EEA, with demand expected to increase due to climate change.

Diffuse pollution from agriculture affects nearly a third of Europe’s groundwaters and surface waters. Nitrates contained in fertilizer and manure are one of the top culprits; they cause rapid growth of certain organisms like algae, which can dominate ecosystems, depleting the water’s oxygen levels and leading to “dead zones” where nothing can grow. In drinking water, nitrates can cause health problems including cancer.

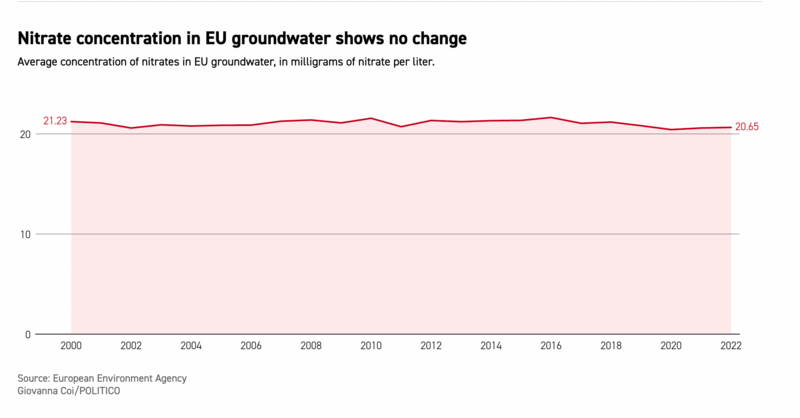

Despite the existence of EU legislation meant to limit the concentration of nitrates in groundwater, progress has been nearly non-existent since 2000. Experts say implementation has been an issue.

The Commission has been reviewing the law since 2023 and is mulling a simplification of existing rules, though a decision on that isn’t expected until toward the end of the year.

Other legislative changes have been more effective. Levels of phosphates — another nutrient that, like nitrates, becomes a pollutant if present in excessive amounts — in rivers more than halved between 1992 and 2011, though progress has been halting since. Stricter rules on urban wastewater treatment and the ban on phosphates in detergents have contributed to the decrease.

Efforts to reduce pollution from intensive pesticide use have also produced results, though the `EEA warned that 10 percent of groundwater areas had failed to achieve good chemical status due to high concentrations of pesticides in 2021.

The agency estimates that the EU is on track to achieve its goal of slashing the use and risk presented by chemical pesticides by half in 2030. The bloc is however much less likely to halve the loss of nutrients (including nitrates) into safe groundwater by the end of the decade.

The price of inaction

Climate change is set to deepen Europe’s water crisis by exacerbating water scarcity in the face of increasing demand.

Droughts are predicted to become more frequent and intense, especially — but not exclusively — in Southern Europe.

Longer dry periods will compromise the water quality and threaten supply to millions of people in Europe. According to the Joint Research Centre (JRC), by 2050 up to 65 million people in the EU and the U.K. could experience water scarcity for parts of the year if greenhouse gas emissions keep increasing.

The Mediterranean region would be most affected, but parts of Central and Northern Europe would also experience significant water pressure due to a variety of factors ranging from mismanagement and poor infrastructure to uncontrolled demand from industry, agriculture and public water supply systems.

The costs to Europe’s economy would be immense. Farming and agriculture will take the brunt of water scarcity, facing reduced yields and increased costs to irrigate the soil and feed animals.

Energy production will also be affected. Nuclear and thermal power plants will have less water for cooling, and hydro plants will produce less electricity. Buildings and infrastructure will suffer damage because of soil shrinkage caused by prolonged droughts.

Meanwhile, exceptionally heavy rainfall will result in more destructive floods; counterintuitively, heavy precipitation does not infiltrate the soil, so it will not help replenish Europe’s strained water supply.

The JRC estimates that the economic damage from drought alone could amount to €12-15 billion by 2050 and up to €45 billion by 2100. Meanwhile, destruction from coastal and river floods will cost up to €287 billion annually by the end of the century.

Curb your enthusiasm

Despite the severity of the impending crisis, the European Commission might not end up delivering the water strategy that is so desperately needed.

A draft of the strategy, obtained by POLITICO, floats the possibility of introducing water abstraction targets, but even if it went ahead with these, the targets would likely be voluntary.

On agriculture, the document proposes rewarding farmers who “engage in structural changes” to improve water management. This would be written into the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Water resilience would become a formal part of work on the CAP, according to the draft document.

It also floats a “simplification” of EU water rules to help their implementation, in line with the Commission’s broader simplification drive. But it has very little to say about nutrient or pesticide pollution.

On forever chemicals, the draft proposes setting up a support mechanism for remediating PFAS and other persistent chemicals, establishing a “Public-Private Partnership for their detection and remediation.”

Taxonomy

- Water Pollution

- Water Supply

- Flint Water Crisis

- Water from Air

- Water from Urine

- water remediation