Conventional Water Treatment, a Disaster for Small Communities

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Technology

For decades, First Nations communities in Canada have consistently dealt with mismatched water treatment systems, and the consequences have been disastrous.

Hans Peterson is the former head of the Saskatchewan Research Council’s Water Quality Team and technical advisor of the Safe Drinking Water Foundation. Some of the nightmares these water treatment operators have had to deal with are:

- Water in the treatment plant with nutrient levels so high that biofilms grow on the membrane filtration equipment and clog it.

- Sand filters that have to be constantly backwashed in order to keep the plant operating and providing water.

- A community without a water treatment plant at all, but with well water with sporadically high levels of arsenic. The operator’s job was to mix and match the water between four wells in order to bring the concentrations of arsenic below government regulations.

These communities have been assigned water treatment plants without enough source water tests to determine whether or not the chosen water treatment technology is appropriate.

Why are these treatment plants chosen in the first place? Two reasons: they are typically cheaper and they utilize conventional water treatment methods that have been around for decades or more.

Civil engineers likely remember being taught the “typical” water treatment process during their undergraduate degree, where the beginning stages are coagulation, flocculation and sedimentation, followed by filtration and disinfection.

Another Conventional Water Treatment Process: Manganese Greensand

Another Conventional Water Treatment Process: Manganese Greensand

Manganese greensand is also considered a typical treatment method.

Manganese greensand is frequently used in utility plants to treat iron, manganese and trace amounts of hydrogen sulfide. These compounds tend to be excessively high in groundwater sources and while they are not necessarily harmful to health, it is still vital that they are removed during treatment. High levels of manganese and iron will damage plumbing fixtures, give water an unpleasant taste and color and provide nutrients to certain strains of bacteria.

In a manganese greensand filtration system, coagulation and flocculation are usually not part of the picture. Instead, the manganese greensand filtration unit is typically preceded by aeration and chlorination (or another type of oxidant addition) and then there may be pH adjustment of the water.

The sand itself is composed of glauconite, a mineral deposited onto the eastern shores of the U.S. and treated with manganese oxides. It is because of this that it has the nickname “New Jersey greensand.”

The sand itself is composed of glauconite, a mineral deposited onto the eastern shores of the U.S. and treated with manganese oxides. It is because of this that it has the nickname “New Jersey greensand.”

The ion exchange properties of the sand were discovered in the early 20th century, when it was used as a slow-release fertilizer for soils. As a water treatment process, manganese greensand has a proven effectiveness and is relatively inexpensive to deploy, making it one of the most popular processes ever implemented.

Moving Forward: Cases Where the Old Methods Have Failed

If you were going to have your house painted and you had to choose between hiring a senior with 25 years of painting experience under his belt and a teenager who hasn’t been in the business very long, you would probably pick the former option.

This kind of thinking has plagued the water treatment industry for years. Conventional treatment methods have had a long record of success—and as a result, there are more people who are trained to operate them, more options for company suppliers, more overall knowledge.

Saddle Lake Cree Nation, Alta.: Coagulation and Ultra-Filtration

Saddle Lake Cree Nation, Alta.: Coagulation and Ultra-Filtration

“If you have a really poor-quality water source, coagulation and filtration are not going to cut it,” said Peterson. For example, look at Saddle Lake Cree Nation, Alta., (Saddle Lake) a First Nations community in which the utility served around 7,000 people. The source water was a lake that was so contaminated, the operators had to treat the water with CAD$15,000 worth of chemicals every month.

These chemicals were part of the overall treatment process, which used advanced coagulation followed by ultrafiltration. When the treatment plant was first built in 1982, the cost of chemicals was just $1,000 per year. This jumped to $200,000 in 2006 after some major plant alterations and it still wasn’t enough to treat the water adequately.

The capital costs of the water treatment plant itself turned out to be a waste since there was no way to optimize the treatment process.

George Gordon First Nation, Sask.: Manganese Greensand

George Gordon First Nation, Sask.: Manganese Greensand

George Gordon First Nation (George Gordon), unlike Saddle Lake, extracted its water from underground wells. However, the water was equally poor and difficult to treat.

“Some of the well-water in Saskatchewan is extremely poor in quality. At 100 or 200 m below ground, the water is brackish and high in ions because the area used to be an inland sea,” Peterson explained. “As a result, we have contaminants such as methane and hydrogen sulfide gases, ammonium, iron and manganese. Arsenic levels in the source water were as also high, reaching 80 µg/L.”

For years, the utility at George Gordon used manganese greensand to treat these contaminants, thinking it would be a simple process. Clearly, it did not pan out that way. “There was just no end of trouble,” said Peterson. “They used to have five manganese greensand filters treating the water and each of them had to be backwashed twice a day.”

Peterson explains the necessary process for regenerating manganese greensand filtration.

“The manganese greensand filtrations units are activated by adding potassium permanganate and then they are left overnight. Then, you dump the water to waste and you rinse the filter and start again. After regeneration, this process is supposed to run for six months; at George Gordon, it was only effective for four hours,” said Peterson.

Before the water treatment upgrade at George Gordon, the water utility operator had easily one of the worst jobs in the country. Faced with the responsibility of providing clean water to the community, he would have to repeatedly backwash the failing filters. According to Peterson, he would work late most nights.

The utility at George Gordon used to have a manganese greensand filter that was followed by chlorination and then distributed. It was found, however, that the treated water still had high levels of manganese, ammonium and arsenic, so a reverse-osmosis (RO) membrane treatment step was implemented in 2001. This just caused more problems.

Residual nutrients such as metals and ammonium created an environment for bacteria to settle and thrive on the concentrated side of the RO membranes. In other words, they became “biologically fouled.”

Biological Filtration: So Far, Successful

Biological Filtration: So Far, Successful

A study from the Water Resource Foundation surveyed water industry professionals about their experience with and perceptions of biological water treatment. The survey found that utility workers and regulatory professionals are typically hesitant to accept its practice—and the most prominent reasons for this are the insufficient full-scale experience and lack of unified understanding.

After years of boil-water advisories, four community members filed a class-action lawsuit against the federal government for inadequately addressing their poor-quality tap water. It’s unfortunate that drastic legal action had to be taken, but it paid off, as government officials responded by providing funds for a research project to examine Yellow Quill’s water.

One of the first decisions made was to change from the surface water supply to a groundwater source. While this raw water was not receiving waste, it was still given the official label of untreatable since it still had a high level of contaminants. Over a period of 22 months, a number of conventional treatment technologies, such as manganese greensand, and advanced treatment technologies, such as biological filtration and ozone, were tested.

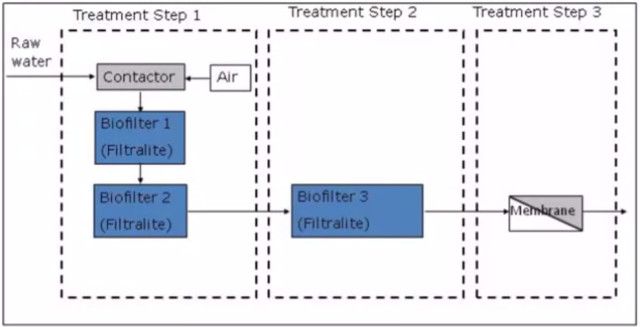

This is where IBROM was developed—and from the way Peterson describes it, the process actually seems fairly simple.

“The well pump pushes the water through a series of biofilters, then a booster pump picks up the water and runs it through the RO membranes, the water is then pH-adjusted, chlorinated and sent to treated water reservoirs,” Peterson explained. “That’s it.”

Peterson states that one of the biggest advantages IBROM has to offer is its ability to treat contaminants without excessive backwashing and chemical applications.

“For example, we actually deal with ten times as much iron biologically as anybody can do through chemical or physical oxidation, so we only need to backwash at a fraction of the rate done before,” said Peterson.

The full-scale IBROM implementation finally lifted the nine-year boil-water advisory at Yellow Quill. Residents were initially skeptical about the safety of their water, but tests from the water treatment plant have assured its cleanliness.

The IBROM process is currently operational in 15 First Nations communities, including Saddle Lake, George Gordon and Yellow Quill. Two additional First Nations communities will introduce IBROM plants before the end of 2016.

Biological treatment has proven advantages, but as with all water treatment systems, its effectiveness does still largely depend on the source water quality, staff training, overall environment and plant set-up. One of the biggest drawbacks is that that biological filtration doesn’t have the historical proven success that conventional treatment has had.

A Bittersweet Success

“The decision-making process when the government chooses which company and system for a First Nations community is quite often based on the lowest-cost bid,” Peterson explained. “This is typically the cheapest option possible—cheap parts, cheap processes—and the result is just a mess. The approval of unproven water treatment processes has turned some First Nations communities into guinea pigs for sometimes hare-brained schemes. This has already resulted in non-working water processes that within a few years have had to be replaced, on the federal government’s tab.”

“Quite often, smaller communities are ‘prescribed’ conventional treatment technologies with little or no source water testing or assessment. I don’t understand how this is acceptable practice,” said Cole. “The tests are relatively inexpensive and by gathering simple data, many potential design mistakes can be avoided.”

“We need to talk openly about technical issues, try to address technical issues,” said Peterson. “Unfortunately, staff needs to answer to the politicians—and they want no bad news about water. I think talking about water issues should be the best news ever.”

Source: engineering.com

Media

Taxonomy

- Treatment

- Drinking Water Treatment

- Purification

- Wastewater Treatment

- Industrial Water Treatment

- water treatment

2 Comments

-

Organica Bluehouse may be a solution to be considered.

http://organicawater.com/organica/products-services/organica-bluehouse -

Thanks Hans. A great article. I too find that the complexities of small water supply systems are always underestimated.