Low-Tech, Affordable Solutions to Improve Water Quality

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Technology

Michigan Tech researchers are developing low-tech, affordable solutions to improve water quality in municipal water tanks, and to remove micropollutants from water using renewable materials.

By Kelley Christensen

Mohammad Alizadeh Fard, a doctoral student in Michigan Tech’s Civil and Environmental Engineering Department, and Brian Barkdoll, professor of civil and environmental engineering, are developing low-tech, affordable solutions to improve water quality in municipal water tanks, and to remove micropollutants from water using renewable materials.

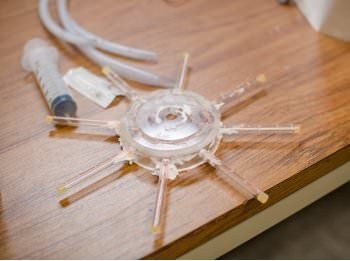

The PVC spraying mechanism that causes the water to circulate constantly within a tank to prevent a stagnant top layer clotted with algae and bacteria. Source: MTU

Their research has been published in three journals—Journal of Hydraulic Engineering (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0001459), Journal of Molecular Liquids (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2017.11.039), and Colloids and Surfaces A(DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2017.08.008)—with a fourth paper pending review. Their work proves that solutions to vexing problems can be elegant in their simplicity.

An Elegant, Low-Tech Solution

In communities around the nation, there are large water-storage tanks for municipal drinking use. Many such tanks have a line in to supply the tank with water, and a line out. However, these lines in and out are frequently at the tank bottom. Though the tanks are refilled daily, the water at the top of the tank is never used and becomes stagnant. Even though many municipal water supplies are treated with chlorine, the top water layer can become a breeding ground for bacteria, algae or waterborne illness, such as giardia and E. coli.

“If the water is not moving, (bacteria and algae) can start growing,” Barkdoll says. “It may not be originally from the water source; it could be from the air. Or the chlorine in the stagnant water could be used up after some time. You want the water to keep moving, especially in hot regions of the country.”

But if there’s a large fire in the community or surrounding countryside, the water tank is drawn down significantly, and people then drink the stagnant water.

“So, when you have a fire, all the stagnant water goes out to everybody’s house,” Barkdoll says. “After a fire, people get sick, that’s a known thing. That’s the problem that we’re trying to fix.”

To remedy the problem, Alizadeh Fard and Barkdoll created shower head-like attachments that can be added to new or existing water tanks for minimal cost. Adding a PVC-pipe sprinkler at the top of the tank, and a reverse sprinkler at the bottom of the tank, injects water into the system and keeps all the water circulating. Alizadeh Fard and Barkdoll published their article on this simple but effective system in the Journal of Hydraulic Engineering March 15. They hope it will be a low-tech solution easy for water quality managers to adopt.

Unseen Menace: Micropollutants

But organic contaminants are not the only source of contaminated water. Few municipal systems are equipped to handle micropollutants—such as pharmaceuticals, hormones, microplastics, nanoparticles in socks and synthetic fleece, and antifungal compounds—even types of industrial waste that are present in very low concentrations. Despite the small amounts—mere micrograms—of these pollutants in water, they still have carcinogenic effects on humans and aquatic creatures. Retrofitting treatment plants to filter for micropollutants is expensive, leading Barkdoll and Alizadeh Fard to explore potential solutions.

“These contaminants have long-term effects on health,” Alizadeh Fard says. “Most of our treatment plants have not been designed to remove them from water, so it’s important to find a reliable solution to address the problem.”

The researchers struck on the idea of adsorbing pollutants from water. Adsorption occurs when molecules essentially stick to a surface. The first method Alizadeh Fard and Barkdoll tested was to use polymer-coated magnetic nanoparticles to adsorb Tonalide (used to mask odors and often found in detergents), Bisphenol-A (better known as BPA, used to make plastics clear and tough), Triclosan (an anti-bacterial and anti-fungal agent used in cleaning products that is now banned), Metolachlor (an herbicide), Ketoprofen (an anti-inflammatory) and Estriol (an estrogen supplement).

The polymer-coated magnetic nanoparticles were most effective at adsorbing Ketoprofen and BPA, removing the pollutants in 15 minutes with 98 and 95 percent effectiveness, respectively, with only 0.1 milligram of the adsorbent.

But what happens once the nanoparticles have done their work? Because the adsorbent is magnetic, the researchers can use magnets to remove the nanoparticles from the water.

Barkdoll and Alizadeh Fard say that one of the key components of their work is that the adsorbents are reusable once rinsed with a restorative methanol solution. In the lab, the polymer-coated nanoparticles were restored and used again five times before seeing decreased effectiveness.

The researchers have also used magnetic carbon nanotubes and activated carbon as absorbents. During the lab trials, the polymer-coated nanoparticles have so far proven to be the most efficient.

Read full article: Michigan Tech

Media

Taxonomy

- Treatment

- Treatment Methods

- Filtration

- Technology

- Filtration Solutions

- Water Treatment Solutions

- Filtration

- water treatment