A Well-Established Industry: The Evolution of Groundwater Monitoring

Published on by Marcus Miller, Digital Marketing Manager at In-Situ in Technology

A Well-Established Industry: The Evolution of Groundwater Monitoring

Groundwater scientists and engineers face unique obstacles when trying to make data collection safer and more efficient. Groundwater monitoring often requires travel to remote, difficult-to-access locations. Then, equipment needs to be deployed underground, out of reach. And that's just the beginning. Developing technology to solve industry challenges requires ingenuity, precision and innovation. We sat down with Technical Consultant Adam Hobson, In-Situ's resident groundwater expert and chief hydrologist, to discuss how groundwater monitoring transformed from labor-intensive manual measurements to the automated, high-resolution data collection of today.

In-Situ: Take us back to the beginning. What did groundwater monitoring look like when In-Situ was founded?

Adam Hobson: Up until the 1970s and 80s, groundwater was primarily measured with manual measurements using electric tape. People would have to travel out to the well and measure the water level with a tape every time they wanted to know what it was. There were other methods, too, like floats and bubblers, that are still used today. They're still considered accurate methods, but they're not as easy to use as a submersible pressure transducer.

In-Situ: What types of transducers were people using?

Adam Hobson: Most pressure transducers were instruments with a pressure transducer and a temperature sensor, but no battery and no data logging. In-Situ had one called a PXD that many hydrogeologists of that generation are familiar with. The all-in-one package with pressure transducer, data logger and power supply hadn't been developed yet. But if you didn't want to use level tape, submersible pressure transducers were an option. And once that was developed, the digital side of things really took off.

In-Situ: What did that look like at the time?

Adam Hobson: In 1976,Chester McKee started In-Situ in his basement in Laramie, Wyoming, U.S., to provide consulting and product support to the in-situ uranium mining industry. He wanted a way to see multiple wells across a large area all at once and created the HERMIT ( H ydrologic, E nvironmental, R emediation and M onitoring I nstrumen T )in 1984.

The HERMIT was a data logger and battery that sat at the surface and provided a hub to connect to multiple PXDs. McKee was developing the all-in-one unit I mentioned earlier, but he hadn't finished it yet. In the meantime, transducers had to be powered from the surface and all the data had to be stored at the surface. So, you would run cables from a PXD in each well and create this big web across the ground, connecting to the hub (the HERMIT) which would program all your pressure transducers into one data logger.

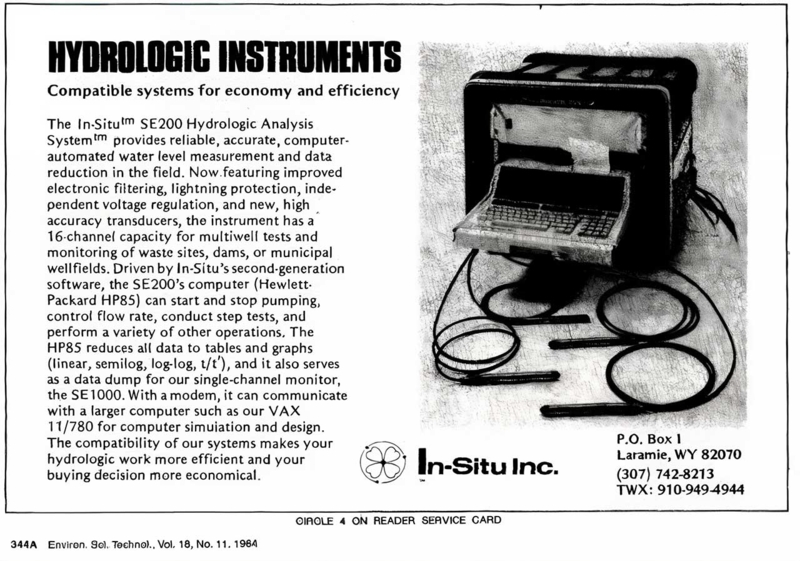

One of In-Situ's first advertisements.

In-Situ: What happened once the HERMIT collected the data?

Adam Hobson: This is where In-Situ started getting into software development because you need an interface to process and analyze your data. We started with Win-Situ. You would connect to the HERMIT via a laptop and you'd have an interface to go in and work with the data on your PC. But again, you had to physically be in the field, with your computer hooked up to the HERMIT. It wasn't a telemetry device that you could access remotely.

In-Situ: What was telemetry like at that time?

Adam Hobson: Telemetry existed, but it wasn't common or affordable. Electronic solutions were cumbersome—massive cabinets and solar panels and big batteries to power the electronics for long periods of time. They were costly to install and maintain and projects often didn't have the space or the resources for that kind of infrastructure. We weren't the first people to create telemetry, but we wanted to make our unit easy to set up and interface with, to expand access to that kind of monitoring.

In-Situ: But we were the first the create the all-in-one datalogger. When did that come along?

Adam Hobson: Yes, McKee introduced the first all-in-one datalogger/pressure transducer/temperature sensor in 1989. It wasn't called a Level TROLL yet—it was the TROLL 4000, but it was essentially the same technology our TROLLs use today. The TROLL 4000 was the first time anyone had fit all those functions in one instrument and made it small enough to deploy in a well.

In-Situ: What inspired Chester McKee to start developing these instruments?

Adam Hobson: A lot of companies design a product and then try to find an application to sell it into—that's not us. Chester McKee was out in the field, doing the work. He saw the challenges hydrogeologists were facing and developed technology to answer those needs. Almost 50 years later, we continue to take that approach.

In-Situ: How did all-in-one loggers change groundwater data collection?

Adam Hobson: Standalone data loggers really revolutionized the industry. Suddenly, you could collect more frequent readings, because you didn't have to send someone to the field every time you wanted to measure water level. Instead of taking a measurement once every three months, I could deploy my logger once, and set it to take a reading every 15 minutes for an entire year without going back out there. It improved our ability to collect baseline data and understand short-term and long-term trends. And you could get better spatial coverage because you're not limited by the length of cables or the proximity of your data logging hub.

So, people could collect more frequent readings and get better spatial coverage while not...

Taxonomy

- Groundwater

- Water Monitoring

- Groundwater Recharge

- Groundwater Assessment

- Groundwater Modeling

- Groundwater Pollution

- Groundwater Prospecting

- Groundwater Mapping

- Surface-Groundwater Interaction

- Groundwater Salinisation

- Groundwater Quality & Quantity

- Water Quality Monitoring

- Groundwater Resource

- Water Quality Monitoring

- Public Water System and Groundwater Issues

- Central Ground Water Board

- Groundwater Surveys and Development

- Groundwater flux

- gaskets, boots for pipe and manhole for groundwater quality

- Groundwater monitoring and assessments

- Groundwater Remediation

- Groundwater Data Scientist