Drought in the Bay Delta & Central Valley

Published on by Ashantha Goonetilleke, Professor, Water/Environmental Engineering at Queensland University of Technology in Academic

California's vast reservoir system, fed by annual snow- and rainfall, plays an important part in providing water to the State's human and wildlife population

There are almost 1,300 reservoirs throughout the State, but only approximately 200 of them are considered storage reservoirs, and many of the larger ones are critical components of the Central Valley and State Water Project facilities. Storage reservoirs capture winter precipitation for use in California's dry summer months. In addition to engineered reservoir storage, California also depends on water "stored" in the statewide snowpack to significantly augment the State's water supply as it melts slowly over the course of the summer.

The Central Valley and State Water Projects are a complex system of reserviors, lakes, dams, pumping plants and conveyance structures. Source: California Department of Water Resources

The Role of Storage Reservoirs

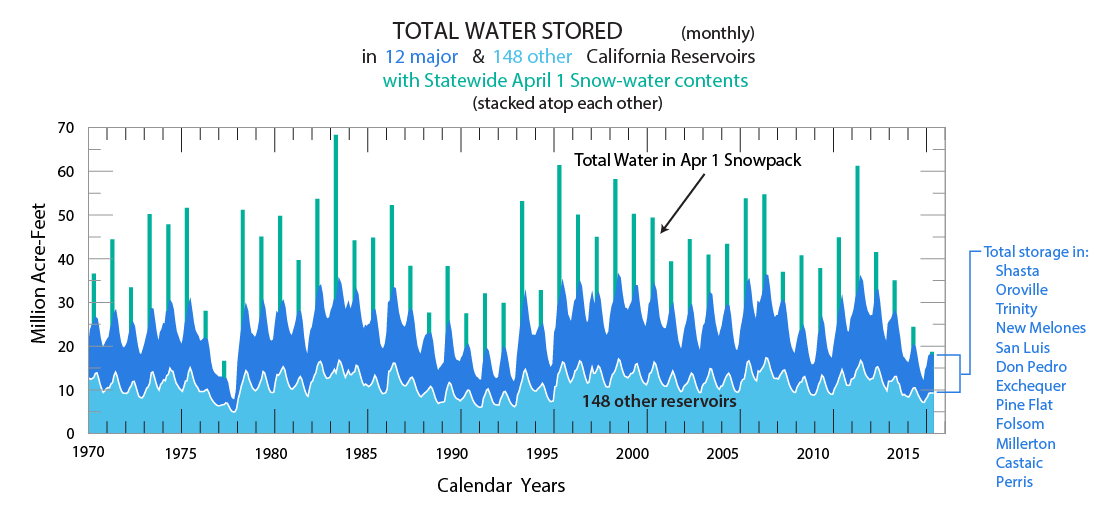

Of the State's almost 200 storage reservoirs, about a dozen major reservoirs hold about half of the water stored in California's reservoirs (Dettinger and Anderson, 2015).

Each of these major reservoirs is multipurpose, and operated to meet environmental mandates, including providing flows and cold water storage for anadromous fish. Nine of these 12 major reservoirs either impound storage in, or provide water supply to, the Sacramento River and San Joaquin River watersheds.

These reservoirs include Shasta, Oroville, Trinity, New Melones, Don Pedro, Exchequer, Pine Flat, Folsom, and Millerton. The other three major reservoirs—San Luis, Castaic, and Perris—are off-stream storage reservoirs built to help optimize the operations of either the Federal Central Valley Project, or the California State Water Project. Many of the smaller reservoirs are operated primarily for hydropower production, and supply millions of megawatts of water-powered electricity to the State's population.

These reservoirs—large and small—all play an important role in keeping the California community thriving. Despite having a cumulative storage capacity of almost45 million cubic acre-feet, these reservoirs currently hold much less than their full capacity for a variety of reasons.

Snow & Reservoirs

Snowpack plays an important role in keeping California's reservoirs full. Winter and spring snowpack typically melt gradually throughout the year, flowing into and refilling reservoirs. Snowpack accounts for the bulk of California's water source and storage, as early spring snowpack "contains about 70% as much water, on average, as the long-term average combination of the major and 'other' reservoirs" (Dettinger and Anderson, 2015).

Recently, Michael Dettinger, a U.S. Geological Survey Research Hydrologist, collaborated with Michael Anderson, California State climatologist, to investigate California's reservoirs' long-term water storage. They looked as far back as 1970 to determine the reservoir's involvement in California's water landscape, specifically studying how annual snowpack has historically impacted the water supply within the 12 major reservoirs and 148 of the smaller reservoirs. They then analyzed the recorded snow water content to determine the total water in the snowpack for every April 1 since 1970. By examining the correlation between these two sets of data, Dettinger and Anderson concluded the 12 major reservoirs have, historically, been operated aggressively to alleviate the impacts of drought and flood. They determined that the inter- and intra-seasonal managed fluctuations of the 148 smaller reservoirs were not as significantly pronounced.

Dettinger and Anderson also used this understanding of the historical relationship between snowpack and reservoir usage to investigate how the current California drought affected reservoir storage. In April 2015, the California Department of Water Resources measured the snow water content as essentially zero. Because the April snow water content helps recharge surface reservoir storage during the spring and summer months, a snow water deficit results in storage reservoirs—depleted throughout the year—to go without crucial refilling. Dettinger and Anderson determined that reservoir replenishment in winter 2015 was only about 9% of normal. Thus in 2015, California's major reservoirs—which are important tools to manage water supply through drought conditions—did not receive the snowpack runoff necessary to refill them after three years of drought. The authors state, "The current challenge to statewide water managers is less the lack of water in the reservoirs and much more the lack of water in snowpack that normally would be expected to melt soon and replenish our reservoirs." Unfortunately, due to the expected consequences of climate change, the lack of snow storage experienced in the current drought could become more the norm than the exception in years to come.

Source: USGS

Media

Taxonomy

- Drought

- Sustainable Water Resource Management

- Water Resource Management

- Water Resources Management