Graphene Could Help Make Desalination More Productive

Published on by Naizam (Nai) Jaffer, Municipal Operations Manager (Water, Wastewater, Stormwater, Roads, & Parks) in Technology

Used in filtration membranes, the ultrathin material could help make desalination more productive.

A single sheet of graphene, comprising an atom-thin lattice of carbon, may seem rather fragile.

But engineers at MIT have found that the ultrathin material is exceptionally sturdy, remaining intact under applied pressures of at least 100 bars. That’s equivalent to about 20 times the pressure produced by a typical kitchen faucet.

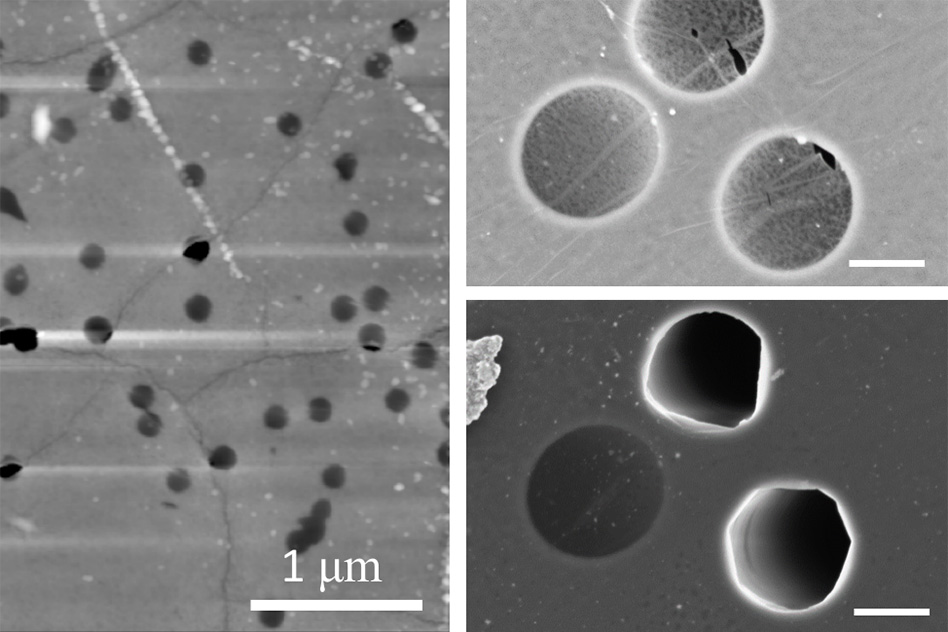

On the left, an atomic-force microscopy image shows a nanoporous graphene membrane after a burst test at 100 bars. The image shows that failed micromembranes (the dark black areas) are aligned with wrinkles in the graphene. On the right, two zoomed-in scanning electron microscopy images of graphene membranes show the before (top) and after of a burst test at pressure difference of 30 bars. The images illustrate that membrane failure is associated with intrinsic defects along wrinkles. Photo: Courtesy of the researchers

The key to withstanding such high pressures, the researchers found, is pairing graphene with a thin underlying support substrate that is pocked with tiny holes, or pores. The smaller the substrate’s pores, the more resilient the graphene is under high pressure.

Rohit Karnik, an associate professor in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, says the team’s results, reported today in the journal Nano Letters serve as a guideline for designing tough, graphene-based membranes, particularly for applications such as desalination, in which filtration membranes must withstand high-pressure flows to efficiently remove salt from seawater.

“We’re showing here that graphene has the potential to push the boundaries of high-pressure membrane separations,” Karnik says. “If graphene-based membranes could be developed to do desalination at high pressure, then it opens up a lot of interesting possibilities for energy-efficient desalination at high salinities.”

Karnik’s co-authors are lead author and MIT postdoc Luda Wang, former undergraduate student Christopher Williams, former graduate student Michael Boutilier, and postdoc Piran Kidambi.

Water stressed

Today’s existing membranes desalinate water via reverse osmosis, a process by which pressure is applied to one side of a membrane containing saltwater, to push pure water across the membrane while salt and other molecules are prevented from filtering through.

Many commercial membranes desalinate water under applied pressures of about 50 to 80 bars, above which they tend to get compacted or otherwise suffer in performance. If membranes were able to withstand higher pressures, of 100 bars or greater, they would enable more effective desalination of seawater by recovering more fresh water. High-pressure membranes might also be able to purify extremely salty water, such as the leftover brine from desalination that is typically too concentrated for membranes to push pure water through.

“It’s pretty clear that the stress on water sources is not going away any time soon, and desalination forms a major source of fresh water,” Karnik says. “Reverse osmosis is among the most efficient methods of desalination in terms of energy. If membranes could operate at higher pressures, this would allow higher water recovery at high energy efficiency.”

Turning the pressure up

Karnik and his colleagues set up experiments to see how far they could push graphene’s pressure tolerance. Previous simulations have predicted that graphene, placed on porous supports, can remain intact under high pressure. However, no direct experimental evidence has supported these predictions until now.

The researchers grew sheets of graphene using a technique called chemical vapor deposition, then placed single layers of graphene on thin sheets of porous polycarbonate. Each sheet was designed with pores of a particular size, ranging from 30 nanometers to 3 microns in diameter.

To gauge graphene’s sturdiness, the researchers concentrated on what they termed “micromembranes” — the areas of graphene that were suspended over the underlying substrate’s pores, similar to fine meshwire lying over Swiss cheese holes.

The team placed the graphene-polycarbonate membranes in the middle of a chamber, into the top half of which they pumped argon gas, using a pressure regulator to control the gas’ pressure and flow rate. The researchers also measured the gas flow rate in the bottom half of the chamber, reasoning that any increase in the bottom half’s flow rate would indicate that parts of the graphene membrane had failed, or “burst,” from the pressure created in the top half of the chamber.

They found that graphene, placed over pores that were 200 nanometers wide or smaller, withstood pressures of 100 bars — nearly twice that of pressures commonly encountered in desalination. As the size of the underlying pores decreased, the researchers observed an increase in the number of micromembranes that remained intact. Karnik says the this pore size is essential to determining graphene’s sturdiness.

“Graphene is like a suspension bridge, and the applied pressure is like people standing on that bridge,” Karnik explains. “If five people can stand on a short bridge, that weight, or pressure, is OK. But if the bridge, made with the same rope, is suspended over a larger distance, it experiences more stress, because a greater number of people are standing on it.”

Read more: MIT

Media

Taxonomy

- Ultrafiltration

- Filtration

- Filtration

- Membrane Technology

- Membrane Filtration

- Filtration

- Graphene