Hong Kong : ACT Department Report – Race For Water

Published on by Kim van Arkel, Scientific Advisor in Association / NGOs

Hong Kong : ACT Department Report

Unlike on the previous stopovers, this time the team did not visit landfills, or other waste management facilities due to time constraints. However, there were many exchanges with environmental activists, companies acting on the matter and government officials. These meetings made it possible to highlight the problems that industrialised countries are facing today, overwhelmed by huge quantities of plastic waste, which found themselves without sufficient infrastructure when China suddenly decided, at the end of 2017, to no longer treat supposedly recyclable waste from abroad due to the environmental and social consequences generated by this business. Hong Kong was then both a gateway for foreign waste to reach Mainland China but also took advantage of the latter’s attractive outlets for its own waste, particularly plastic waste.

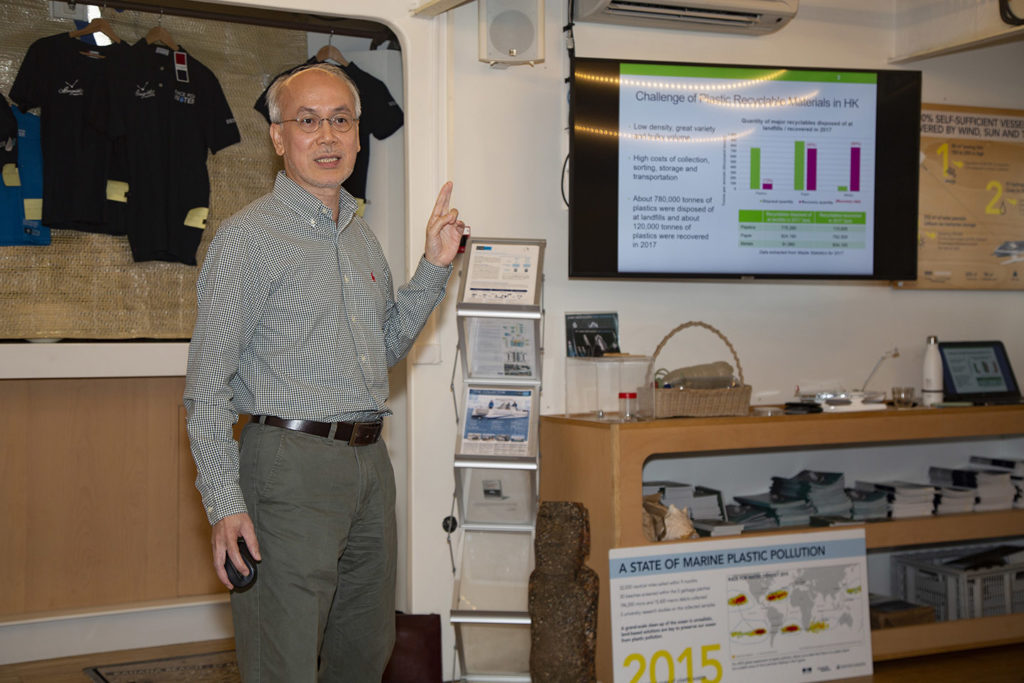

During the traditional “Plastic Waste to Energy” workshop held on board the Race for Water vessel at each stopover – which aims to bring together the public, private and civil society sectors to discuss the problem of plastic – Mr W.Y. Wong, from the Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department, began his presentation with the challenge managing plastic waste. The costs of collecting, separating, cleaning and preparing it for effective recycling are enormous. In 2017, when Mainland China had not yet closed its doors to plastics, of the 900,000 tonnes generated in Hong Kong, only 120,000 tonnes were collected for recycling. 83% then was sent to China, 5% to other Asian countries and only 12% was recycled locally. For the remaining 780,000 tonnes of plastic waste, there is no alternative to landfilling. The Hong Kong megalopolis has three landfills currently in service, all of which have already exceeded their capacities.

The 2018 figures are expected by the end of November. The share of landfill is expected to be even higher for want of market outlets for the waste.

Mr Wong then presented us with the pilot project that the government has just launched for two years on the collection of household plastic waste. Today, only 10,000 tonnes are recovered by the city from households. The low collection rate is apparently mainly due to a lack of public confidence in the recycling system. The objective of this pilot project is therefore to test a free plastic collection at home in three representative districts of the territory (Est, Kwun Tong and Sha Tin). The collected plastic waste would then be transformed locally into raw material or directly into recycled products so that the population could regain confidence throughout the chain.

The pilot project will also cover plastic waste from schools and public agencies and includes the establishment of mobile collection points, as well as educational activities to encourage a wider public to participate in the recycling of plastic waste. The data obtained and the experience gained will then be used to implement the service throughout the country.

The announcement of this pilot project was met with a mixed feelings from the workshop participants, particularly when it came to the budget allocated to the project, which seemed very limited compared to its ambitions. And on the real possibility of recycling all these plastics when we know that a large part of them pose health problems or are not mechanically recyclable.

This is why China has closed its doors. 30 to 40% of the plastics they received from abroad could not be recycled, ended up in the wild or burnt in the open air, causing serious pollution of the air, soil and water, and health problems for the surrounding populations.

Therefore, many of the people we met deplored the government’s lack of serious interest in environmental issues. The energy production still mainly based on coal and the basic waste management, are clearly the sticking points. However, the territory generates nearly US$ 15 billion profits each year and has the capacity to be exemplary.

We received the visit of Mr. Wong Kam Sing, Minister of the Environment of Hong Kong, together with several representatives of the Environment Bureau and the Environmental Protection Agency. They also invited 15 “coastal cleanliness heroes” selected from local organisations fighting plastic pollution in Hong Kong Bay. Mr. Wong Kam Sing told us that the fight against plastic pollution was one of the major topics discussed by the government and that the following six action points were currently under consideration:

We received the visit of Mr. Wong Kam Sing, Minister of the Environment of Hong Kong, together with several representatives of the Environment Bureau and the Environmental Protection Agency. They also invited 15 “coastal cleanliness heroes” selected from local organisations fighting plastic pollution in Hong Kong Bay. Mr. Wong Kam Sing told us that the fight against plastic pollution was one of the major topics discussed by the government and that the following six action points were currently under consideration:

– the implementation of a system concerning liability of producers of plastic bottles

– an environmental tax regime on plastic bags

– the reduction of plastic packaging in the retail industry

– the elimination of plastic microbeads in cosmetics

– the deployment of smart water fountains and zero plastic education campaigns on school campuses

– a pilot project for plastic-free lunches in elementary and secondary schools

Let us hope that these commitments are not merely empty announcement effects and that these actions will be implemented quickly. Because in terms of local consumption patterns, very few of the 7.5 million inhabitants seem to be aware of the mountains of waste that are accumulating around their city and of the urgent need to reduce these volumes. Starting with the omnipresent overpackaging in shops and the quantity of takeaway meals sold every day, often in polystyrene trays, to feed a hyperactive population that has not a minute to spare.

Doug Woodring , founder of the NGO Ocean Recovery, also spoke during the workshop and gave us some background information. The quantity of plastic bottles consumed each year, for example, can cover the entire Port Victoria area. This represents nearly 5 million bottles consumed per day. Yet water is drinkable in Hong Kong.

However, for Doug, most of the plastic pollution of Hong Kong waters comes from the Pearl River Delta in Mainland China, where 80 million people live, and where poor waste management combined with heavy seasonal rainfall results in an overwhelming amount of waste on the Hong Kong coast at the mouth of the river. This phenomenon is repeated almost every year; yet, nothing is put in place to at least try to recover most of the outflow.

The consequences are visible down in the depths of the oceans, as shown by the quantities of waste discovered by our teams alongside Harry Chan, who led us to a real underwater dump located in a bay on Lamma Island. This 60-year-old retired man is fighting body and soul to preserve the oceans, especially from the ghost nets and plastic waste that are accumulating on the seabed. He regularly organises underwater clean-ups and promotes widespread understanding about these gloomy maritime treasures in order to raise awareness. Especially since the bay in which we dived is also home to fish farms, and welcomes every weekend many tourists who come to swim and taste the seafood specialities…

Harry is not the only one fighting against these destructive models. Many NGOs have been created on the island to raise awareness amongst the communities and push decision-makers for change. There are increasingly more bulk product distributors and influencers are working on the matter of alternative solutions.

Doug Woodring also shares our vision that the greatest power and duty for change lies at the corporate level. But he notes a lack of rules and incentives. This leads to this excessive waste production. “Any retailer and producer can do as they wish today and has no obligation to recover their packaging, and therefore make it totally recyclable, or easy to process. Yet they are the ones who put them on the market. They must therefore find ways to give their packaging a second life.”

Some companies have cottoned on and are getting started. This is the case of the Carrefour Group, whose sustainable development manager for Asia, Romain Zanna-Bellegarde, showed us how the company succeeded in stopping the use of 50 million single-use plastic bags in a single decision. These “polybags” are used extensively to transport and protect products from their production site to distribution sites. Carrefour individually packaged each of these clothing items designed in Asia and sold in Europe. They have simply stopped this practice, which is considered unnecessary and harmful, and now advocate bulk transport. They are also exploring alternatives to plastics, particularly for foodstuffs, such as trays made from waste paddy fibres, which are currently being tested in Europe in some of their supermarkets. They are mainly looking to involve other companies in order increase their influence with their suppliers and encourage them to reduce their use of plastic.

Doug advocates, in this sense, for more financial incentives such as tax cuts, which would be an incentive for more innovation, and more entrepreneurs to invest in infrastructure or new technologies to meet the complex and global challenge of plastic pollution.

So there are many initiatives to fight against plastic pollution, but the challenge is still far from over. Time is running out for Hong Kong (its businesses, government and people) to realise the value of its environment and not jeopardise the health of the population and the richness of local biodiversity.

Camille Rollin , responsable ACT

Source: Race for Water

Media

Taxonomy

- plastic debris

- microplastics

- Plastic Ban

- Single-use plastic

- Beat Plastic Pollution