How Switzerland's 100 STEPs Remove Micropollutants

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Technology

Christian Abegglen leads a Swiss Wastewater Association external team dedicated to facilitating a Swiss government programme to equip 100 STEPs (known in French-speaking cantons as 's tations d’épuration des eaux ' , or STEPs) with anti-micropollutant technologies.

By Celia Luterbacher

The goal of the programme, which came into force on January 1 2016, is for each STEP to filter out 80% of all micropollutants.

To achieve this goal at the Werdhölzli STEP, which serves roughly 440,000 people, construction is underway to install a process called ozonation.

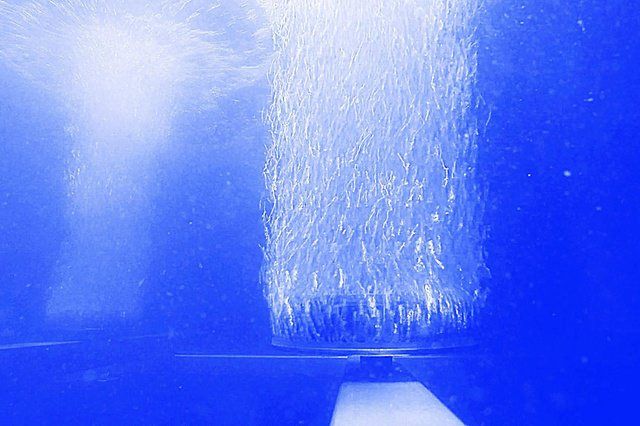

Bubbling ozone gas through wastewater is one way to neutralise micropollutants – a growing environmental threat. (Eawag)

"Ozone is an aggressive gas. We add it to the cleaned wastewater, and it then attacks the micropollutants and actually destroys the molecules. There are some fragments leftover, which are less toxic or non-toxic, and so the negative effects that we see in the wastewater after that are gone,” Abegglen explains.

Ozone gas is generated from oxygen and electricity at the STEP. After being used to treat the wastewater, the gas is completely removed, and only oxygen is expelled at the end of the cycle. It’s a clean and effective process, but there are drawbacks: it is energy-intensive, and can leave behind harmful by-products such as bromate, which must be tightly controlled.

When construction is finished in 2018, the Zurich facility will join two other successfully retrofitted STEPs in Dübendorf, canton Zurich, and Herisau, canton Appenzell Outer-Rhodes.

A drop in the ocean

For Shannon and Roger Erismann, leaders of a volunteer water pollution monitoring project called hammerdirt.chexternal link, there’s a bigger picture to be addressed when it comes to protecting Swiss waterways: the thousands of pieces of trash that are dumped into lakes and rivers daily.

“Micropollutants are hugely important. But if we’re pretending in Switzerland that we can model the human brainexternal link, why can’t we solve the problem of the cigarette butt in the water?” asks Roger.

One problem, the Erismanns explain, is that larger pieces of litter – in addition to acting as pollutants themselves – degrade into tiny particles that accumulate more chemicals over time.

Read full article: Swiss Info

Media

Taxonomy

- Ozonation

- Reclaimed Wastewater

- Micropollutants

- Purification

- Ozone

- Wastewater Treatment