Largest Single-site Microbiome Gene Catalog Constructed to Date

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Academic

In a recent report published in Nature Microbiology, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (UHM) Oceanography Professor Ed DeLongand his team report the largest single-site microbiome gene catalog constructed to date.

With this new information, the team discovered nutrient limitation is a central driver in the evolution of ocean microbe genomes.

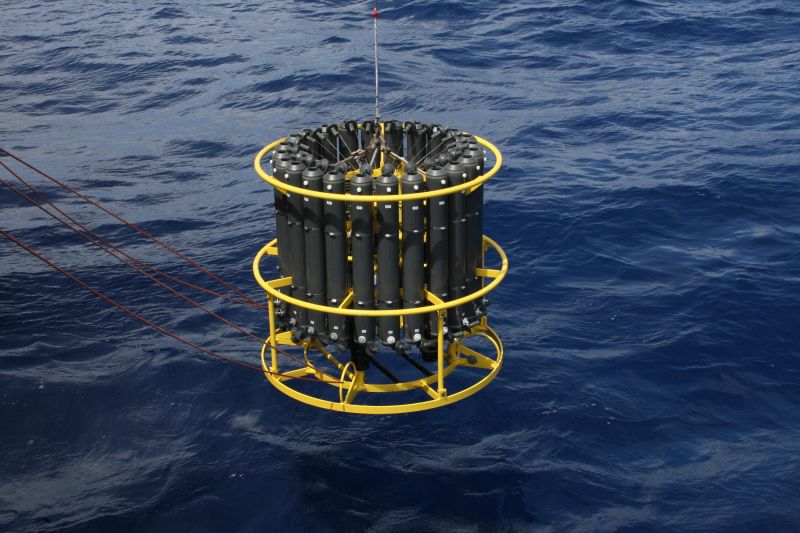

A rosette sampler captures water at specified depths at Station ALOHA. Credit: Tara Clemente, UHM.

As a group, marine microbes are extremely diverse and versatile with respect to their metabolic capabilities. All of this variability is encoded in their genes. Some marine microorganisms have genetic instructions that allow them to use the energy derived from sunlight to turn carbon dioxide into organic matter. Others use organic matter as a carbon and energy source and produce carbon dioxide as a respiration end-product. Other, more exotic pathways have also been discovered.

“But how do we characterize all these diverse traits and functions in virtually invisible organisms, whose numbers approach a million cells per teaspoon of seawater?” asked DeLong, senior author on the paper. “This newly constructed, comprehensive gene catalog of microbes inhabiting the ocean waters north of the Hawaiian Islands addresses this challenge.”

Water samples were collected over two years, and modern genome sequencing technologies were used to decode the genes and genomes of the most abundant microbial species in the upper 3,000 feet of water at the Hawai‘i Ocean Time-series (HOT) Program open ocean field site, Station ALOHA.

Just below the depth of sunlit layer, the team observed a sharp transition in the microbial communities present. They reported that the fundamental building blocks of microbes, their genomes and proteins, changed drastically between depths of about 250-650 feet.

“In surface waters, microbial genomes are much smaller, and their proteins contain less nitrogen—a logical adaptation in this nitrogen-starved environment,” said Daniel Mende, post-doctoral researcher at the UHM School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) and lead author on the paper. “In deeper waters, between 400-650 feet, microbial genomes become much larger, and their proteins contain more nitrogen, in tandem with increasing nitrogen availability with depth.”

Read full article: University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

Media

Taxonomy

- Ecosystem Management

- Microbiology

- Ecosystem Management

- Marine

- Oceanographic Survey

- Ocean engineering