Membrane That Can Better Treat Wastewater, Recover Valuable Resources

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Technology

A membrane made up of block polymers has the customizable and uniform pore sizes needed for filtering or recovering particular substances from wastewater, researchers say in a review published in Nature Partner Journals - Clean Water.

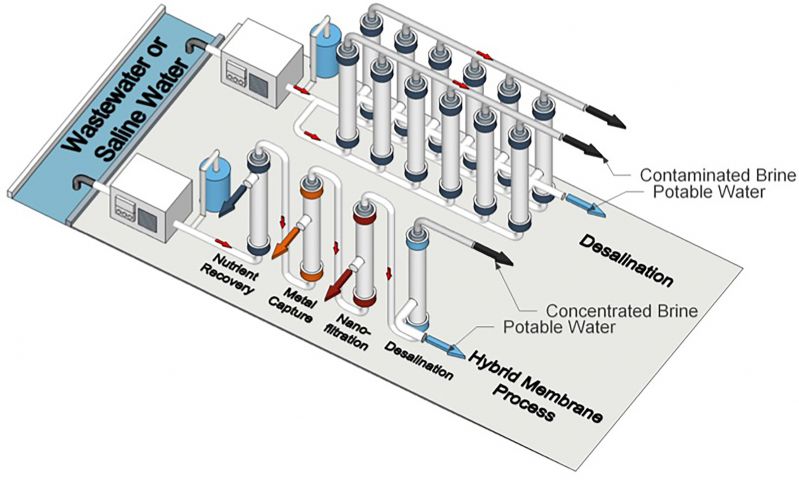

Researchers propose that current desalination processes and future hybrid ones use a block polymer membrane to treat unconventional water sources. (University of Notre Dame image/Yizhou Zhang), Via: Purdue

Some parts of the world have an increasing need to generate drinkable water from wastewater due to excessive chemical discharge into typical water sources or lack of rainfall. Researchers from Purdue University and the University of Notre Dame believe that a block polymer membrane could not only improve desalination and filtration of wastewater, but could also be used in forthcoming hybrid water treatment processes that simultaneously recover substances for other purposes.

“Current nanofiltration membranes used for desalination tend to separate things based on size and electrostatic interactions, but not chemical identity,” said Bryan Boudouris, Purdue’s Robert and Sally Weist Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering. “If we tailor the right membrane to the right application to begin with, then less energy is used.”

One problem with nanofiltration membranes is irregular pore sizes that tend to allow too much of a substance into the filtered water. Due to strong covalent bonds that tie together the blocks of different polymers in a block polymer membrane, nanoscale holes as opposed to macroscale ones form between the polymers. This results in a denser pattern of smaller pores all the same size throughout the membrane, which engineers can adjust in order to prohibit the entry of a variety of particles.

Block polymers also address the fact that different substances respond to membranes differently due to chemical properties. Modifying the third block, which lines the inside of a pore opening, attracts certain molecules over others.

“The third block is something we can control reasonably well and, hopefully, that’s ultimately controlling the rejection or absorption of things in the water or fluid that you want to remove,” said David Corti, Purdue professor of chemical engineering.

The ability to customize pore size and chemistry means that block polymer membranes could more effectively recover valuable resources, such as gold and silver, and heavy metals that should be disposed of in a particular way or collected for other uses, Boudouris said.

In so doing, the membranes would be ideal for eventual hybrid water treatment processes, which desalinate water as well as recover nutrients and capture metals.

“In future hybrid processes, a desalination step may be a final finishing step to produce potable water after several upstream steps are used to recover material or energy from a stream of wastewater,” said William Phillip, University of Notre Dame associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

While block polymer membranes would be slightly more expensive to produce than nanofiltration membranes, their resiliency and ability to reduce chemical demands for membrane cleaning mean less capital investment and environmental impact.

“If the potential of block polymer membranes for desalination applications can be realized, and these membranes are more selective and more resilient than current state-of-the-art desalination membranes, their increased cost could be offset by the ability to reduce the operating and capital costs of desalination,” Phillip said.

The multifunctionality of a block polymer is not limited to water treatment facilities; backpackers could also make use of these membranes during hiking excursions.

“Filters utilized by backpackers are equipped with a variety of different types of size-selective membranes, so block polymer films could be utilized as potential replacements,” Phillip said.

This paper is available open-access at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41545-018-0002-1

Source: Purdue University

Media

Taxonomy

- Reclaimed Wastewater

- Technology

- Membranes

- Wastewater Treatment

- Chemistry

- Membrane Technology

- Membrane Filtration

- Membrane distillation

1 Comment

-

Couldn't agree more....use our innovative product. Goal is 99.9% and includes desalination