MIT Students Find a Way to Make Stronger Concrete with Plastic Bottles

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Technology

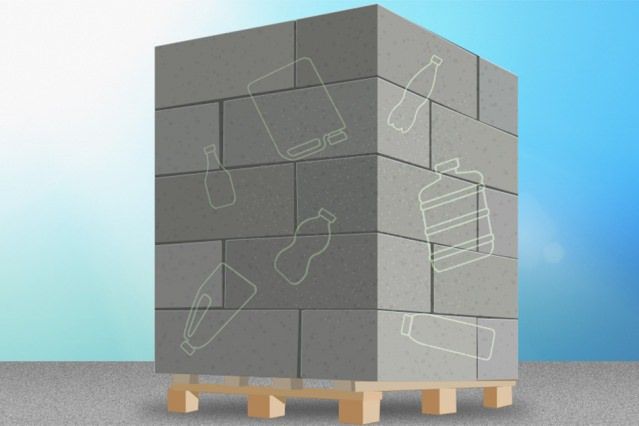

Adding bits of irradiated plastic water bottles could cut cement industry’s carbon emissions.

Discarded plastic bottles could one day be used to build stronger, more flexible concrete structures, from sidewalks and street barriers, to buildings and bridges, according to a new study.

“Our technology takes plastic out of the landfill, locks it up in concrete, and also uses less cement to make the concrete, which makes fewer carbon dioxide emissions,” says assistant professor Michael Short. Image: MIT News

MIT undergraduate students have found that, by exposing plastic flakes to small, harmless doses of gamma radiation, then pulverizing the flakes into a fine powder, they can mix the irradiated plastic with cement paste and fly ash to produce concrete that is up to 15 percent stronger than conventional concrete.

Concrete is, after water, the second most widely used material on the planet. The manufacturing of concrete generates about 4.5 percent of the world’s human-induced carbon dioxide emissions. Replacing even a small portion of concrete with irradiated plastic could thus help reduce the cement industry’s global carbon footprint.

Reusing plastics as concrete additives could also redirect old water and soda bottles, the bulk of which would otherwise end up in a landfill.

“There is a huge amount of plastic that is landfilled every year,” says Michael Short, an assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering. “Our technology takes plastic out of the landfill, locks it up in concrete, and also uses less cement to make the concrete, which makes fewer carbon dioxide emissions. This has the potential to pull plastic landfill waste out of the landfill and into buildings, where it could actually help to make them stronger.”

“This is a part of our dedicated effort in our laboratory for involving undergraduates in outstanding research experiences dealing with innovations in search of new, better concrete materials with a diverse class of additives of different chemistries,” says Büyüköztürk, who is the director of Laboratory for Infrastructure Science and Sustainability. “The findings from this undergraduate student project open a new arena in the search for solutions to sustainable infrastructure.”

After the compression tests, the researchers went one step further, using various imaging techniques to examine the samples for clues as to why irradiated plastic yielded stronger concrete.

The team took their samples to Argonne National Laboratory and the Center for Materials Science and Engineering (CMSE) at MIT, where they analyzed them using X-ray diffraction, backscattered electron microscopy, and X-ray microtomography. The high-resolution images revealed that samples containing irradiated plastic, particularly at high doses, exhibited crystalline structures with more cross-linking, or molecular connections. In these samples, the crystalline structure also seemed to block pores within concrete, making the samples more dense and therefore stronger.

“At a nano-level, this irradiated plastic affects the crystallinity of concrete,” Kupwade-Patil says. “The irradiated plastic has some reactivity, and when it mixes with Portland cement and fly ash, all three together give the magic formula, and you get stronger concrete.”

“We have observed that within the parameters of our test program, the higher the irradiated dose, the higher the strength of concrete, so further research is needed to tailor the mixture and optimize the process with irradiation for the most effective results,” Kupwade-Patil says. “The method has the potential to achieve sustainable solutions with improved performance for both structural and nonstructural applications.”

Read full article: MIT

Media

Taxonomy

- Drinking Water Treatment

- Environmental Policy

- Environment

- Heavy Construction

- Bottled Water

1 Comment

-

This is really exciting to read about th