The High Cost of Algae Blooms in U.S. Waters: More Than $1 Billion in 10 Years

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Case Studies

The High Cost of Algae Blooms in U.S. Waters: More Than $1 Billion in 10 Years

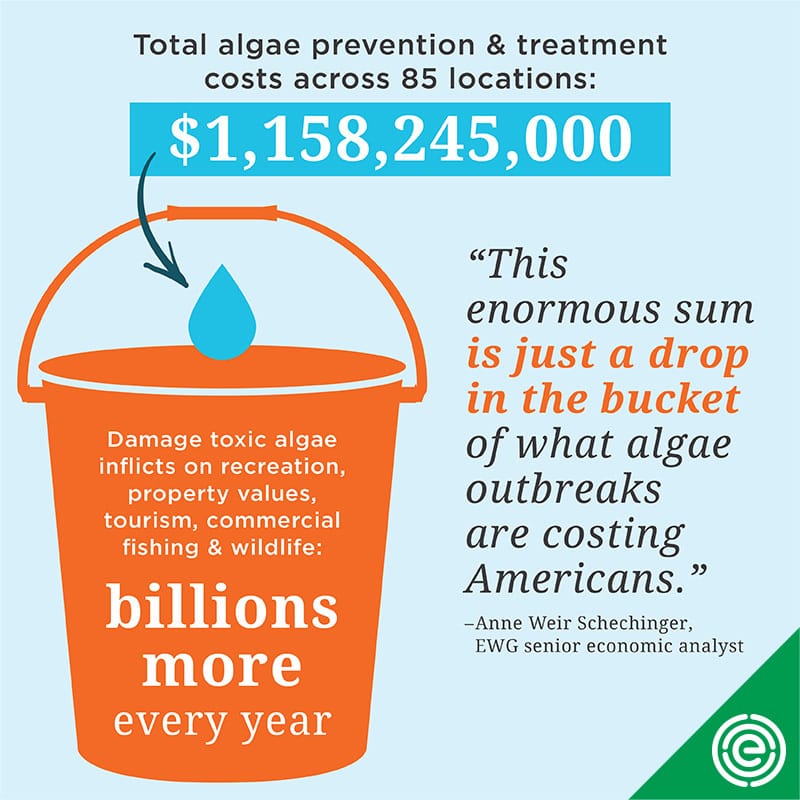

Communities across the United States have spent more than $1 billion since 2010 dealing with outbreaks of potentially toxic algae in lakes, rivers, bays and drinking water supplies, according to an analysis by the Environmental Working Group.

We identified 85 locations, mostly cities and towns, in 22 states that spent money to prevent or treat algae blooms in the past 10 years. The staggering price tag: about $1,158,245,000. This is a first attempt to calculate the cost to communities.

Algae outbreaks can produce toxins that pose serious health hazards to people, pets and aquatic life. Despite a huge surge in reported outbreaks in recent years, the federal government only tracks outbreaks in the largest lakes. Some states do a better job, but they do not always record the cost of dealing with the problem.

To calculate the estimated cost nationwide, EWG searched news databases for reports of algae outbreaks, and what communities have spent to protect or clean up the bodies of water they depend on for household use, recreation and tourism.

Algae Blooms Cost U.S. Communities More Than $1 Billion Since 2010

| State | Total Costs | Locations |

|---|---|---|

| Ohio | $815,184,000 | 11 |

| Oregon | $75,000,000 | 1 |

| Texas | $66,859,627 | 1 |

| California | $52,947,800 | 6 |

| New York | $49,730,000 | 8 |

| Iowa | $40,665,000 | 6 |

| Florida | $19,950,000 | 5 |

| Washington | $16,165,720 | 8 |

| South Carolina | $4,150,000 | 1 |

| New Jersey | $3,326,520 | 8 |

| Minnesota | $3,143,231 | 6 |

| Kansas | $2,943,580 | 4 |

| Wisconsin | $2,570,000 | 3 |

| North Carolina | $1,300,000 | 1 |

| Massachusets | $1,056,012 | 5 |

| Vermont | $1,000,000 | 1 |

| Maine | $745,000 | 3 |

| West Virginia | $700,000 | 1 |

| Missouri | $381,000 | 3 |

| Illinois | $380,000 | 1 |

| Pennsylvania | $37,800 | 1 |

| Michigan | $10,000 | 1 |

| Total | $1,158,245,290 | 85 |

Source: EWG search of news databases, 2010-2020

Here is a list of all locations and what they have spent.

Communities in Ohio – where a 2014 outbreak in Lake Erie made Toledo’s tap water unsafe to drink – spent more than all other states combined: more than $815 million in documented expenses, or 70 percent of the total cost in all locations. Oregon was second, with $75 million, all in the capital city of Salem, where a 2018 outbreak in a nearby lake also forced a do-not-drink warning.

EWG’s ongoing tracking has found more than 1,000 communities with news reports of algae blooms in 49 states since 2010 – an increase of more than 600 percent in the past decade. The locations are plotted on the interactive map below, with links to reported details.

Our estimate does not include losses to recreation, tourism, commercial fishing, wildlife or other economic fallout from algae outbreaks, which could collectively cost communities billions more every year.

Slimy, Smelly and Dangerous

Blooms of blue-green algae – which are technically not algae, but tiny, one-celled organisms – are triggered by chemical nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus when they get into bodies of water. Heat and sunlight make the problem worse: As water heats up throughout the summer, algae blooms get bigger and occur more often. In farming areas, runoff from crop fields treated with commercial fertilizer or manure are the main sources of nutrients that feed these blooms. In some urban areas, nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater and stormwater also contribute to outbreaks.

Algae blooms can spread a smelly blanket of slime across the water. The blooms contain bacteria that can produce dangerous cyanotoxins, which cause nausea, vomiting and longer-term effects, such as liver failure and cancer, when people are exposed through recreational contact or consume the toxins through drinking water. Simple activites we all enjoy in the summer – swimming, boating, sitting on a beach or even walking near a body of water – can make people and animals sick if the water is infected. Every year, dogs die from exposure to toxic algae.

Not all algae outbreaks are toxic, but even trained experts can’t tell the difference without testing. Most of the algae cleanup expenses documented in the news stories EWG tracks are likely related to toxic algae, but it is impossible to know for sure, since the articles do not always identify whether a bloom is toxic.

Treatment and Prevention

As our research shows, treating an algae outbreak once it has infested a lake or contaminated a water supply can be extraordinarily expensive.

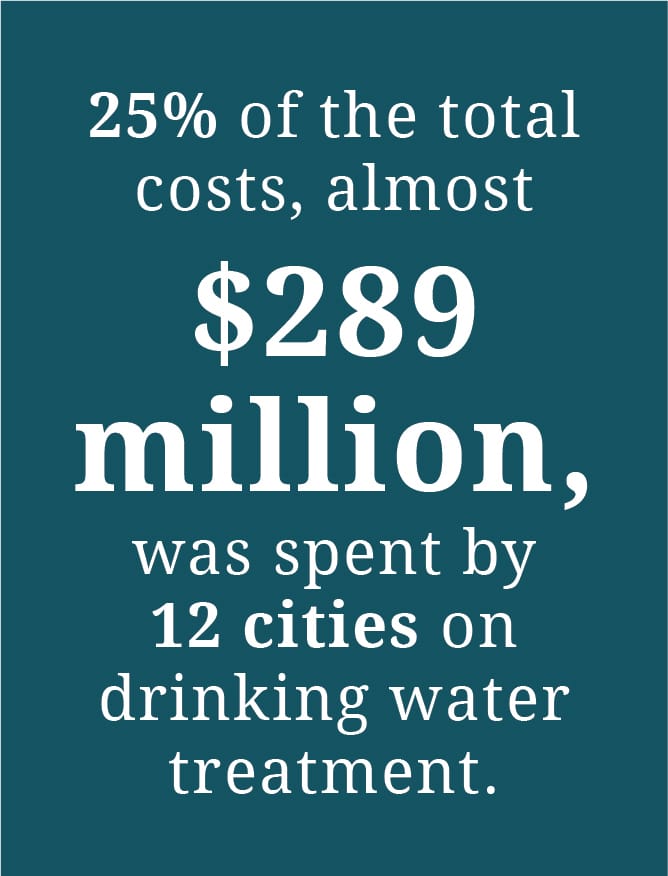

Communities whose drinking water comes from a source contaminated by an algae outbreak can install technology to remove bacteria and toxins. Granular activated carbon or powdered activated carbon are the most common. EWG found that 12 cities spent almost $289 million – 25 percent of the total costs we documented – on drinking water treatment. That includes the money communities like Toledo have invested in wholesale improvements to their drinking water systems.

On smaller lakes, many communities treat algae outbreaks in the water instead of focusing on prevention. A common practice is to spray aluminum sulfate, or alum, onto the bloom, which causes the algae and phosphorus to sink to the bottom of the lake, although the phosphorus could be stirred up again by heavy rainfall from a big storm. Out of the 85 locations we examined, 18 used alum to treat an outbreak, at a total cost of about $9.4 million.

What makes more sense than expensive, after-the-fact treatment is prevention – keeping phosphorus and nitrogen from polluting water in the first place. But that’s not always so simple.

Under federal law, farm fields are considered non-point sources of pollution, meaning it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact provenance of farm runoff. As a result, individual farmers are not held accountable for what flows off their fields and into nearby waters.

On the other hand, wastewater treatment plants are considered point sources of pollution, with discharges that can be traced back to their origins. It’s often easier to reduce pollution from point sources, even though agriculture may be the bigger problem in a particular area.

Consider this conundrum in Ohio.

Experts agree that agriculture contributes more nutrients to Lake Erie than cities and towns do, especially given the explosive growth in animal feeding operations in the Maumee River watershed. Yet Toledo and Akron together have spent $637 million on stormwater and wastewater infrastructure improvements since 2014, when Toledo issued a do-not-drink order to more than 400,000 residents for several days because of high levels of cyanotoxins entering the water supply from Lake Erie.

Taxonomy

- Algal Blooms