The Roots of Venezuela's Appalling Electricity Crisis

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Government

Venezuela's massive electricity crisis keeps getting worse and worse.

This week, President Nicolás Maduro declared that every Friday for the next two months will be a national holiday, a desperate move to conserve power as water levels at the country's hydroelectric dams fall to perilously low levels. "We'll have long weekends," he said on state television, leaving people to ponder what this would mean for schools and stores.

This came after Maduro had closed the entire country for five days during Easter holidays in March. The latest announcement is part of a new 60-day emergency plan to avoid a shutdown of key hydropower facilities, which would plunge Caracas into darkness. Bloomberg reports that malls and hotels will now have to generate their own power for nine hours a day. Heavy industries will need to cut electricity use by 20 percent. It's a disaster for a country already reeling from recession, high inflation, and food shortages. (The crash in global oil prices hit Venezuela especially hard.)

How did things get so bad? Partly this is a story about drought. More than 60 percent of Venezuela's electricity comes from hydropower, and a lack of rainfall this winter due to El Niño has led to low water levels at its all-important Guri Dam.

But the bigger story here is that Venezuela's socialist government has badly mismanaged the electric grid for years. Since 2000, the country has failed to add enough electric capacity to satisfy soaring demand, making it incredibly vulnerable to disruptions at its existing dams. Venezuela has been enduring periodic blackouts and rationing ever since 2009 — and there's no sign things will improve anytime soon.

How Venezuela mismanaged its electric grid — leading to perennial blackouts

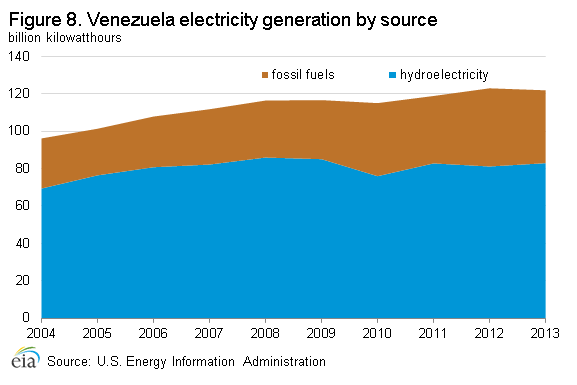

To understand why Venezuela, a country with the world's biggest oil reserves, keeps suffering from energy shortages, we have to look at the country's grid. The vast majority of the country's electricity comes not from fossil fuel generators but from hydroelectric dams:

Most of the time, hydropower is a clean, reliable source of electricity. The trouble occurs when there's a drought and water levels in the reservoir fall too low to spin the dam's turbines. That's what's happening at Venezuela's massive Guri Dam, which provides 75 percent of Caracas' electricity. If water levels fall four more meters, which could happen by the end of April, operators have to shut the turbines off.

Most of the time, hydropower is a clean, reliable source of electricity. The trouble occurs when there's a drought and water levels in the reservoir fall too low to spin the dam's turbines. That's what's happening at Venezuela's massive Guri Dam, which provides 75 percent of Caracas' electricity. If water levels fall four more meters, which could happen by the end of April, operators have to shut the turbines off.

This problem isn't unique to Venezuela: any place that relies on dams faces this risk. California has seen its hydro output plummet in the past few years amid a historic dry spell. The difference is that California has excess electric capacity elsewhere — natural gas turbines, mainly — that it can fire up to compensate.

Venezuela, crucially, doesn't have a good backup plan if its dams fail. And that's where the years of mismanagement come in.

In the 2000s, after Hugo Chávez came into office, investment in new electric capacity in Venezuela dried up, particularly after he nationalized the grid in 2007. But demand for power kept soaring after the government froze electricity rates in 2002 and began subsidizing consumption. More and more people bought air conditioners, TVs, and so on. Today, Venezuela's per capita rate of electricity use is one of the highest in Latin America.

Those two trends put a severe strain on the grid. "Between 2003 and 2012," notes the US Energy Information Administration, "Venezuela’s electricity consumption increased by 49% while installed capacity expanded by only 28%, leaving the Venezuelan power grid stretched." It doesn't help that many households connect to the grid illegally, tapping into existing power lines.

The first big crisis hit in 2009-'10, when an extended drought caused water levels at the Guri Dam to plummet. Rolling blackouts ensued, and the government struggled to cope,forcing companies to take a week-long holiday, fining large electricity users for excessive consumption, and ordering businesses, factories, and mines to reduce output. Chávez's popularity plummeted to the lowest point of his presidency.

In the months after, the government scrambled to fix the situation, spending $1.5 billionto install backup diesel generators throughout the country. It wasn't nearly enough. A year later, experts were warning that only a quarter of those generators were even operational due to a lack of maintenance. And the country's transmission lines remained in shoddy shape, unable to handle major fluctuations. Corruption, incompetence, underfunding — it's all there.

So the electricity crisis never really receded. Further blackouts hit in 2011, in 2012, in 2013, in 2014, in 2015, and now again in 2016. And there's no end in sight.

What would it take to fix Venezuela's grid?

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6207515/GettyImages-453154115.0.jpg)

This is fine. We're okay with the events that are unfolding currently. (Juan Barreto/AFP/Getty Images)

Back in 2011, the Inter-American Dialogue asked a number of the country's energy experts how Venezuela could fix its electricity woes. They all basically said the same thing — "a well-executed investment plan."

Venezuela needs upgrades to its existing dams, reliable sources of backup power during droughts, and a sturdy grid. That all costs money and requires competent oversight.

And that's easier said than done. For instance, experts say one big reason for the lack of investment is that electricity rates were kept artificially low after 2002. Reversing this situation, and hiking people's power bills, is never going to be a popular move. Yet the alternative has been even uglier.

There have been a few minor moves in the direction of reform: In 2014, the governmentdid begin to pare back subsidies for electricity consumption in some regions. But during the latest crisis, Maduro hasn't laid out much of a long-term plan. Instead, he's largely blamed El Niño and mysterious "saboteurs" for the shortages. And the government has mainly focused on short-term rationing and gimmicky holidays, just as it has during previous crises.

"This plan for 60 days, for two months, will allow the country to get through the most difficult period with the most risk," Maduro said on state television Wednesday,according to Bloomberg. "I call on families, on the youth, to join this plan with discipline, with conscience and extreme collaboration to confront this extreme situation."

Source: VOX

Read More Related Content On This Topic - Click Here

Media

Taxonomy

- Energy Consumption

- Energy

- Energy Conservation