The Struggle to Track Ocean Plastic

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Academic

Scientists know that there is a colossal amount of plastic in the oceans. But they don’t know where it all is, what it looks like or what damage it does.

Bottles, fishing nets, ropes, shoes and toothbrushes are among the tons of waste washed up here, thanks to a combination of ocean currents and local eddies.

A study in 2011 reported that the top sand layer could be up to 30% plastic by weight. It has been called the dirtiest beach in the world, and is a startling and visible demonstration of how much plastic detritus humanity has dumped into the world’s oceans.

A study in 2011 reported that the top sand layer could be up to 30% plastic by weight. It has been called the dirtiest beach in the world, and is a startling and visible demonstration of how much plastic detritus humanity has dumped into the world’s oceans.

From Arctic to Antarctic, from surface to sediment, in every marine environment where scientists have looked, they have found plastic.

Other human-generated debris rots or rusts away, but plastics can persist for years, killing animals, polluting the environment and blighting coastlines. By some estimates, plastics comprise 50–80% of the litter in the oceans.

Newspapers tell stories of the ‘Great Pacific garbage patch’, a region of the central Pacific where plastic particles accumulate, and volunteers participate in beach clean-ups across the globe.

Scientists are still struggling to answer the most basic questions: how much plastic is in the oceans, where, in what form and what harm it’s doing. That’s because science at sea is hard, expensive and time-consuming. It is difficult to comprehensively survey vast oceans for small — sometimes microscopic — plastic fragments, and few researchers have made this their line of work.

Where does it come from?

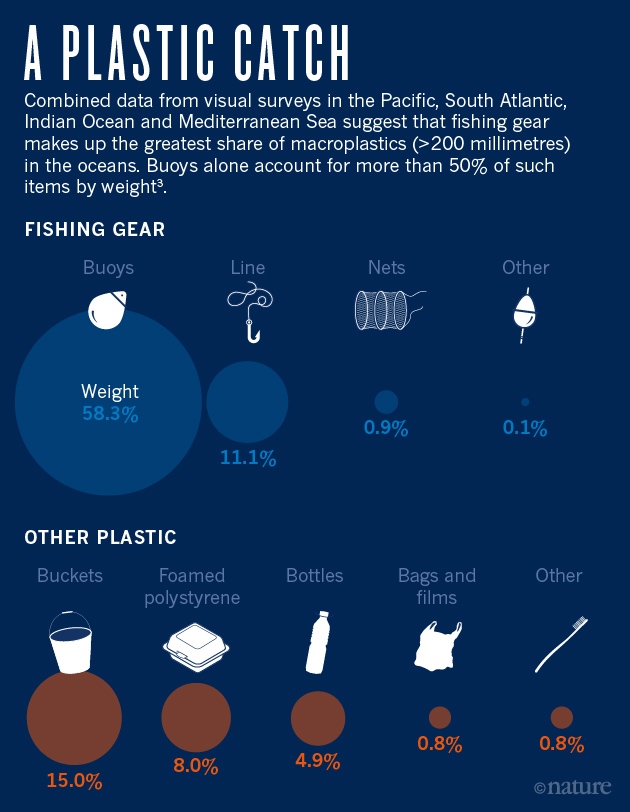

Nets and other fishing equipment that have been lost or discarded at sea are thought to make up a large fraction of marine plastic. An estimate from UNEP suggests that this ‘ghost’ fishing gear makes up 10% of all marine litter, or around 640,000 tonnes.

There is much more than that. Global production of plastics rises every year — it is now up to around 300 million tonnes — and much of it eventually ends up in the ocean. Plastic litter is left on beaches, and plastic bags blow into the sea.

In a 2014 paper, Eriksen and his team analysed data on the items found in a series of expeditions across the world’s oceans and estimated that 87% by weight of floating plastic was greater than 4.75 millimetres in size.

The list included buoys, lines, nets, buckets, bottles and bags (see ‘A sea of plastic’). But when the pieces were counted instead of weighed, large plastics made up just 7% of the total. Many plastic items break down under the onslaught of sunlight and waves until they eventually reach microscopic sizes, and other plastics are small from the start, such as the ‘microbeads’ that are added to face scrubs and other cosmetic products, and that go down the drain.

How much is out there?

How much is out there?

If surveying the ocean for plastic is expensive and difficult at the surface, it’s even harder below it: researchers lack samples from enormous areas of the deep sea that have never been explored.

And even if they could survey all these regions, the concentration is typically so dilute that they would have to test huge volumes of water to get reliable results. Instead, they are forced to estimate and extrapolate.

In a paper published last year, a team led by Jenna Jambeck, who researches waste management at the University of Georgia in Athens, estimated how much waste coastal countries and territories generate, and how much of that could be plastic that ends up in the ocean.

The group reached a figure of 4.8 million to 12.7 million tonnes every year — very roughly equivalent to 500 billion plastic drinks bottles. But her estimate excluded the plastic that gets lost or dumped at sea, and all the plastic that is already there.

Where is it?

The mismatch between the estimated amount of plastic entering the oceans and the amount actually observed has come to be known as the ‘missing plastic’ problem.

Adding to the puzzle, data from some locations do not show a clear increase in plastic concentrations over recent years, even though global production of the materials is soaring.

Public attention has focused on the Great Pacific garbage patch, where plastics collect thanks to an ocean current called a gyre.

The name is something of a misnomer — visitors to the patch would not find piles of seaborne rubbish. A study from 2001 reported 334,271 pieces of plastic per square kilometre in the gyre.

This is the largest tally recorded in the Pacific Ocean, but still works out as roughly one small fragment for every three square metres.

Modelling by van Sebille and his colleagues suggest that concentrations could be several orders of magnitude higher in the Pacific garbage patch, and an equivalent zone in the North Atlantic, than elsewhere.

But the plastic here is accounted for in surveys, whereas the missing plastic is, by definition, missing and therefore somewhere else.

What harm does it do?

What harm does it do?

Researchers know that marine plastic can harm animals. Ghost fishing gear has trapped and killed hundreds of animal species, from turtles to seals to birds.

Many organisms also swallow pieces of plastic, which can accumulate in their digestive system. According to one often-quoted figure, around 90% of seabirds called fulmars washed ashore dead in the North Sea had plastic in their guts.

What’s less clear is whether this pollution has major impacts on populations.

Lab studies have demonstrated the toxicity of microplastics, but these often use concentrations that are much higher than those found in the oceans.

People who say plastics won’t be an issue in the oceans need to take a look at the evidence again.

But some scientists say that at the moment microplastics are probably within safe environmental limits in most places.

What should we do?

Despite the lack of comprehensive data about ocean plastics, there is a broad consensus among researchers that humanity should not wait for more evidence before taking action. Then the question becomes, how?

One controversial project has been devised by The Ocean Cleanup, a non-profit group that by 2020 hopes to deploy a 100-kilometre-long floating barrier in the Great Pacific garbage patch. The group claims that the barrier will remove half of the surface plastic there.

In a paper published earlier this year, van Sebille and his colleague Peter Sherman showed that it would be much more effective to place clean-up equipment near the coasts of China and Indonesia, where much of the plastic pollution originates.

“The closer to the plastic economy loop you intervene the better it is,” van Sebille says. “We’ve got to stop it in the treatment plants, in the landfills. That is the point to intervene.” Eriksen likens the situation to addressing air pollution, where people have long realized that filtering the air is not a long-term solution.

Filtering the oceans seems similarly implausible, he says. “What we’ve seen worldwide is you go to the source.” That means reducing the use of plastic, improving waste management and recycling the materials to stop them from reaching the water at all.

Some types of floating plastic might disappear in just a few years, but plastic will have left its mark, as layers of tiny particles embedded in sediment on the ocean floor.

Source: Nature

Media

Taxonomy

- Environment

- Pollution

- Polymers & Plastics

1 Comment

-

My research is bent with a process, what may solve the problem with all organic wastes includes plastics in oceans. I am looking for the interested partner-investor only to support the implementation of second stage testing, because the process doesn't have scientific explanation. My research was stopped by scientist experts when I presented an independent investment application to government organization to get financial support for second stage tests that to compose the scientific proof for process content and effect. I hope that here a real thinking people who have the resources to support such project that to clean our oceans and coasts.