Time for Water Pricing Overhaul

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Government

Americans Got Used to Paying Little for a Whole Lot of Pristine Water

This summer, a 90-year-old water pipe burst under Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, sending a geyser 30 feet into the air and a flood of troubles over the UCLA campus. Raging water and mud trapped five people, swamped 1,000 cars and flooded five university buildings — blasting the doors off elevators and ruining the new wooden floor atop the Bruins' storied basketball court.

As the campus dried out, though, Angelenos seemed less upset about the replaceable floorboards at Pauley Pavilion than they were over another loss: 20 million gallons of freshwater wasted in the middle of the worst drought in California history. L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti took heat for his earlier campaign promise not to raise water rates in a city with a long backlog of repairs for aging water pipes.

Five days after the L.A. pipeline rupture, officials in Toledo, Ohio, declared the tap water for half a million people unsafe to drink, tainted by toxic algae spreading in the warm waters of Lake Erie. As residents of one of the most water-blessed regions in the world waited in lines to buy bottled water, an issue that had held little political urgency rose near the top of Ohio's gubernatorial and legislative races. Former Toledo mayor Mike Bell held back an "I told you so" for council veterans who'd resisted rate increases to pay for upgrades to the city's 73-year-old water-treatment plant.

In Los Angeles and Toledo and across the U.S., historic drought, water-quality threats heightened by warming waters and poorly maintained infrastructure are converging to draw public attention to the value of fresh, clean water to a degree not seen since Congress passed the Clean Water Act in 1972. The problems are also laying bare the flawed way we pay for water — one that practically guarantees pipes will burst, farmers will use as much as they can and automatic sprinklers will whir over desiccated aquifers.

Squeezed by drought, U.S. consumers and western farmers have begun to pay more for water. But the increases do not come close to addressing the fundamental price paradox in a nation that uses more water than any other in the world while generally paying less for it. And some of the largest water users in the East, including agricultural, energy and mining companies, often pay nothing for water at all.

As a result, we're subsidizing our most wasteful water use — while neglecting essentials like keeping our water plants and pipes in good repair. "You can get to sustainability," says David Zetland, a water economist and author of the book Living with Water Scarcity. "But you can't get there without putting a price on water."

Cheap, Abundant Illusion

Water is the most essential utility delivered to us each day, meeting our drinking and sanitation needs and many others, from fire protection to irrigation. Incongruously, it is also the resource we value least. This is true generally for both the way we use water and the price we put on it.

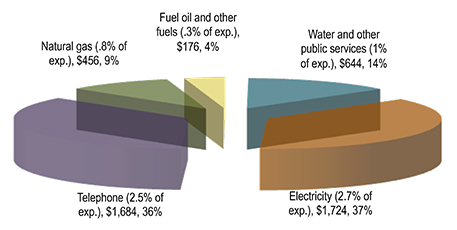

Utility expenditures for a four-person household in 2012. Graphic courtesy of Michigan State University Institute of Public Utilities.

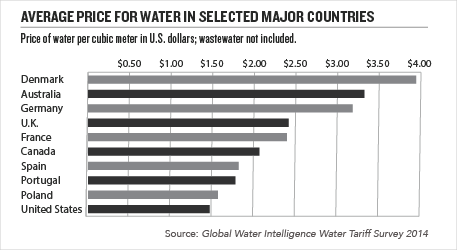

On the global scale, Americans pay considerably less for water than people in most other

developed nations. In the U.S., we pay less for water than for all other utilities. That remains true in these times of increasing water stress, says Janice Beecher, director of the Institute of Public Utilities at Michigan State University, whose data show the average four-person household spends about $50 a month for water, compared with closer to $150 for electricity and telephone services.

Water's historically cheap price has turned the U.S. hydrologic cycle abjectly illogical. Pennies-per-gallon water makes it rational for homeowners to irrigate lawns to shades of Oz even during catastrophic droughts like the one gripping California. On the industrial side, water laws that evolved to protect historic uses rather than the health of rivers and aquifers can give farmers financial incentive to use the most strained water sources for the least sustainable crops. In just one example, farmers near Yuma, Ariz. — the driest spot in the United States, with an average rainfall of 3 inches per year — use Colorado River water to grow thirsty alfalfa; under the law of the river, if they don't use their allotment, they'll lose their rights to it.

For both municipal waterworks and those that carry irrigation water to farms, the illusion of cheap, abundant water arose with the extensive federal subsidies of the mid-20th century. The Bureau of Reclamation built tens of billions of dollars worth of irrigation and supply projects that were supposed to have been reimbursed by beneficiaries; most were not repaid. After passage of the Clean Water Act and the Safe Drinking Water Act in the 1970s, the feds doled out billions more dollars, this time to local communities to help upgrade water plants and pipes. Since ratepayers didn't have to bear the costs, they didn't balk at treating water destined for toilets and lawns to the highest drinking-water standards in the land.

Americans got used to paying wee little for a whole lot of pristine water. At the same time, many utilities delayed the long-term capital investments needed to maintain their pipes and plants. Water boards are often run by local elected officials, making decisions uneasily political. A board member with a three-year term might not vote for a water project that would pay off in year six. Officials who tried to raise rates risked being booted out of office. It was easier to hope federal subsidies would continue to flow. They did not. A Reagan Administration phase-out of water-infrastructure grants began 25 years ago. Over the past decade, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency water infrastructure funding has declined (with the exception of 2009, the year of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act), and policy has shifted from grants to loans.

Unfortunately for water utilities, the timing coincided with the arrival of requirements to scrub dozens of newly regulated contaminants out of drinking water and record numbers of water mains and pipes bursting due to age and extreme temperatures, both hot and cold.

Read More Related Content On This Topic - Click Here

Media

Taxonomy

- Water Management

- Pricing