Unleashing Tehran’s ‘Water Renaissance’

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Government

If the capital of Iran can combine ancient systems of water governance– qanat–with modern information technology, it could drought-proof the capital and protect its citizens from the threats of water insecurity.

By Montgomery Simus

Tehran panorama, Source: Wikimedia

For centuries Tehran, the booming Persian city of 14 million people, has all too often grown by sacrificing its past.

Zealous urban ‘modernisers’ flattened ancient bazaars, widened traditional streets, demolished historic walls, and re-zoned old neighbourhoods into an orderly grid. The water and wastewater company drilled deep wells, blocked rivers, and built huge, new treatment plants.

Yet for all the modern infrastructure, Tehran never outgrew the timeless limit imposed by water.

By embracing its centuries-old heritage, Tehran may set in motion a kind of hydraulic renaissance.

A return to old ways

Mobasherfar has witnessed recent TV ads and billboards throughout Tehran alerting citizens that the city is lacking proper water resources, but feels increased awareness is not enough. Informed middle-class Tehranis care more about saving water, yet the city’s water needs keeps growing.

“The municipality of Tehran is making these educational initiatives one of its highest priorities,” she says. “But people must do more than just talk about the issues if they want to leave something behind for the next generation in their city and neighbourhood.”

So what more can the city do? To move ahead, progressive Tehranis have begun looking back.

Before launching costly new works, some focus on technical maintenance, rehabilitation of wastewater treatment, and repair of outdated water transfer systems.

Others look to the clouds and beyond city limits. They urge investments in roof gardens and green infrastructure. Tehran “should be an extension of our natural environment,” argues Kaveh Samiei, a landscape architect and expert in designing ecological high-rise residential complexes, writing on www.thenatureofcities.com. “Nature has rules by which it operates, and these must be built into urban designs that mesh the organic and inorganic parts of the city.”

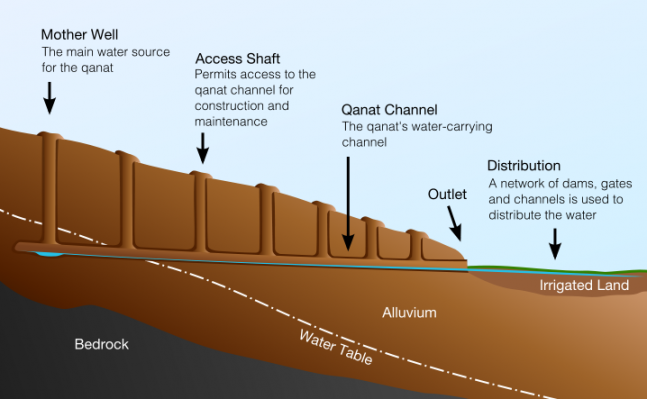

Pushing even further, some suggest repurposing Persia’s ancient indigenous system, qanat.

Qanat – both a technology and form of governance–established Iran’s primacy in self-regulating, allocating, and trading water in ways that maximise its productive, efficient, and politically effective use. By voluntarily exchanging shares of water, those who invest in the system enjoy not only the rights but also the responsibilities to use their water resources wisely, and trade what they save to others.

Qanat established Iran’s primacy in self- regulating, allocating, and trading water, Source: Wikimedia

Tehran is of course no longer the society it was when qanats originally proliferated. People don’t have face-to-face negotiations over transfers in water. But perhaps they don’t need to. Tehranis have cloned Uber. Airbnb is already there.

These online platforms empower people in the sharing economy, and suggest a kind of ‘iQanat’ system can potentially unlock and ‘crowd source’ water from families and firms in a city already dominated by mobile phones, tablets and laptops.

Read full blog: Cities Today

Media

Taxonomy

- Governance

- Water Access

- Technology

- Water Supply

- Integrated Urban Water Management

- Integrated Water Management

- Urban Water

- Water Supply

- Urban Water Infrastructure

- Water Resources Management