Upstream Trenches, Downstream Nitrogen

Published on by Naizam (Nai) Jaffer, Municipal Operations Manager (Water, Wastewater, Stormwater, Roads, & Parks) in Academic

Farmers use tile drainage to keep their fields from being waterlogged. Tile pipes keep the fields dry but send large amounts of nitrogen downstream

Water quality scientist Laura Christianson is working on a solution to the “dead zone”—an area with dangerously low levels of oxygen— in the Gulf of Mexico. Christianson lives over a thousand miles north of the Gulf in Illinois. But human activity in the Mississippi River basin, which connects to the Gulf, can lead to major water quality issues downstream.

In many Midwestern states, farmers use tile drainage to keep their fields from being waterlogged. Pipes buried three to four feet below the surface route water into the Mississippi watershed. The tile pipes keep the fields dry, but they also send large amounts of nitrogen downstream. Nitrogen is a naturally occurring nutrient in the soil and a common ingredient in fertilizer. Extra nitrogen, from fertilizing, causes problems for aquatic ecosystems.

In many Midwestern states, farmers use tile drainage to keep their fields from being waterlogged. Pipes buried three to four feet below the surface route water into the Mississippi watershed. The tile pipes keep the fields dry, but they also send large amounts of nitrogen downstream. Nitrogen is a naturally occurring nutrient in the soil and a common ingredient in fertilizer. Extra nitrogen, from fertilizing, causes problems for aquatic ecosystems.

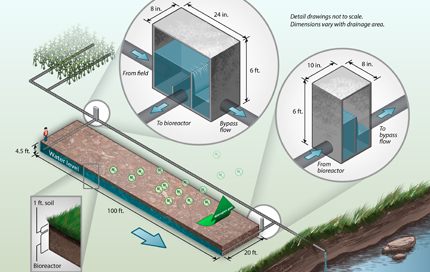

Christianson researches ways to reduce the amount of nitrogen that moves downstream with woodchip-filled trenches. Their job is to intercept the water’s journey from field to rivers and streams. The trenches are called bioreactors.

The trenches themselves aren’t the main heroes. It’s the bacteria that live in them that neutralize the nitrogen threat. “Good bacteria colonize the woodchips, and use them as food,” said Christianson. This concentrated food source gives bacteria extra energy to convert nitrogen into benign gas. Christianson said she was captured by the simplicity of bioreactors. “We’re enhancing a natural process,” she said. “There’s an elegance to it.”

The trenches themselves aren’t the main heroes. It’s the bacteria that live in them that neutralize the nitrogen threat. “Good bacteria colonize the woodchips, and use them as food,” said Christianson. This concentrated food source gives bacteria extra energy to convert nitrogen into benign gas. Christianson said she was captured by the simplicity of bioreactors. “We’re enhancing a natural process,” she said. “There’s an elegance to it.”

Rainfall and irrigation pulls nitrogen from the soil and deposits it in the ocean, where algae feed on it. Eventually the algae outcompete other life forms for sunlight and oxygen. Further, when the algae die, the decomposition process eats up all the dissolved oxygen in the water. The resulting “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico is over 5,000 square miles.

Bioreactors have a simple construction. Although sizes vary, a typical trench is 100 feet long and 20 feet wide, and covered by one foot of top soil. The trench is generally 3.5 feet deep and filled with carbon-rich food sources for bacteria, like woodchips or corn. Tile pipes from the fields are re-routed through the trench before flowing into the stream.

Bioreactors have a simple construction. Although sizes vary, a typical trench is 100 feet long and 20 feet wide, and covered by one foot of top soil. The trench is generally 3.5 feet deep and filled with carbon-rich food sources for bacteria, like woodchips or corn. Tile pipes from the fields are re-routed through the trench before flowing into the stream.

Despite the simple design, there are complex challenges when using bioreactors. “We’re constantly trying to improve the design,” said Christianson. “Much like humans, bacteria don’t do their job as well when they are cold.” The bacteria aren’t as efficient at reducing nitrogen in the Midwestern spring months, when the snow melt starts filtering through. Bioreactors also need to be refilled every ten years or so with woodchips or another source of carbon to keep the bacteria well fed.

Attached link

https://www.agronomy.org/science-news/upstream-trenches-downstream-nitrogenMedia

Taxonomy

- Fertilizers

- Bioreactor

- Stormwater Management

- Stormwater

- Stormwater Runoff