US Rivers are Becoming Saltier – and it’s Not Just From Treating Roads in Winter

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Academic

In a study published earlier this year, it was found that a cocktail of chemicals from many human activities is making U.S. rivers saltier and more alkaline across the nation.

By Sujay Kaushal, Gene E. Likens, Michael Pace, Ryan Utz

Surprisingly, road salt in winter is not the only source: construction, agriculture, and many other activities also play roles across regions.

These changes pose serious threats to drinking water supplies, urban infrastructure and natural ecosystems. Salt pollution is not currently regulated at the federal level, and state and local controls are inconsistent.

Our research shows that when salts from different sources mix, they can have broader impacts than they would individually. It also shows the importance of supporting water quality monitoring nationwide, so that we can detect and address other pollution problems that have yet to be recognized.

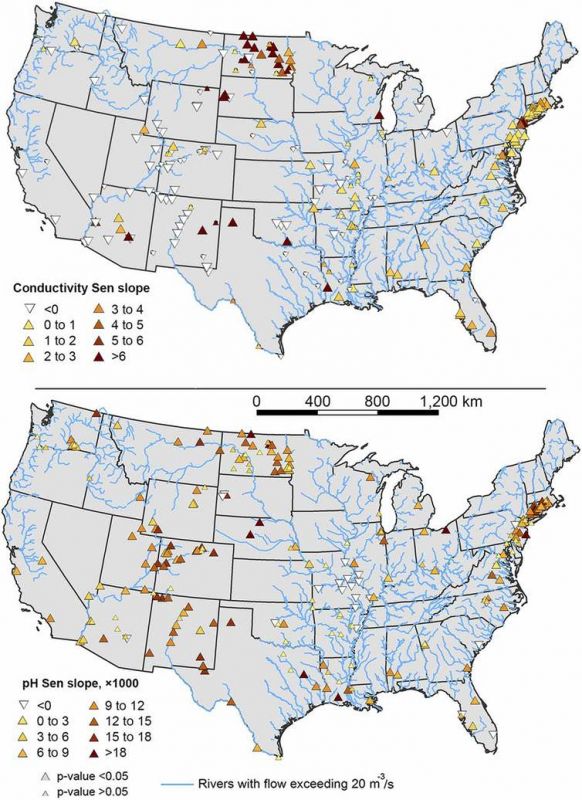

Locations of increasing, decreasing and/or no trends in specific conductance and pH in stream water throughout the continental United States. High-electrical conductivity indicates salinity because salty solutions are full of charged particles that conduct electricity. Kaushal et al., 2018, CC BY-ND, Via: The Conversation

Identifying freshwater salinization syndrome

Our study on human-accelerated weathering showed that along with sodium chloride, other dissolved salts were increasing in fresh water across large regions of the eastern United States. This made us wonder whether there could be a link to our previous work on salinization in these regions.

We started to recognize that in theory, salt pollution and human-accelerated weathering could be sending increasing quantities of salts that were alkaline into rivers throughout the nation, and that this could increase their pH levels. We knew that ocean water, which is naturally salty, has a higher pH than fresh water because it has accumulated high levels of alkaline salts. After much analysis, we proposed that similar interconnected processes could influence salinity and pH in fresh water.

Many sources release alkaline salts into the environment, including weathering of impervious surfaces, fertilizer and lime use in agriculture, mine drainage, irrigation runoff and winter use of road salt. Initially, parts of these alkaline salts bind to soil. But when they come into contact with sodium – for example, excess road salt – chemical reactions occur that release the alkaline salts, which then wash into freshwater ecosystems.

We called this process freshwater salinization syndrome because it was producing multiple effects on salts, alkalinity and pH, which are fundamental chemical properties of water.

Read full article: The Conversation

Media

Taxonomy

- Decontamination

- Resource Management

- Water Resource Management

- Contaminant Removal

- River Studies

- Contaminant Movement Mapping

- River Engineering

- River Restoration