Water Consumption Labelling

Published on by Peter Neill, Director, World Ocean Observatory in Business

Would it not be useful to know a rating of water use—how much is used, where it comes from, and how production waste is disposed of—before we make an educated, mindful purchase?

In my most recent book, THE ONCE AND FUTURE OCEAN: Notes Toward a New Hydraulic Society I argue for greater public understanding of how we consume water, how we price water, and how we manage water as the single most important resource on earth and as the key component in a new paradigm for value, structure, and behavior in the 21st century.

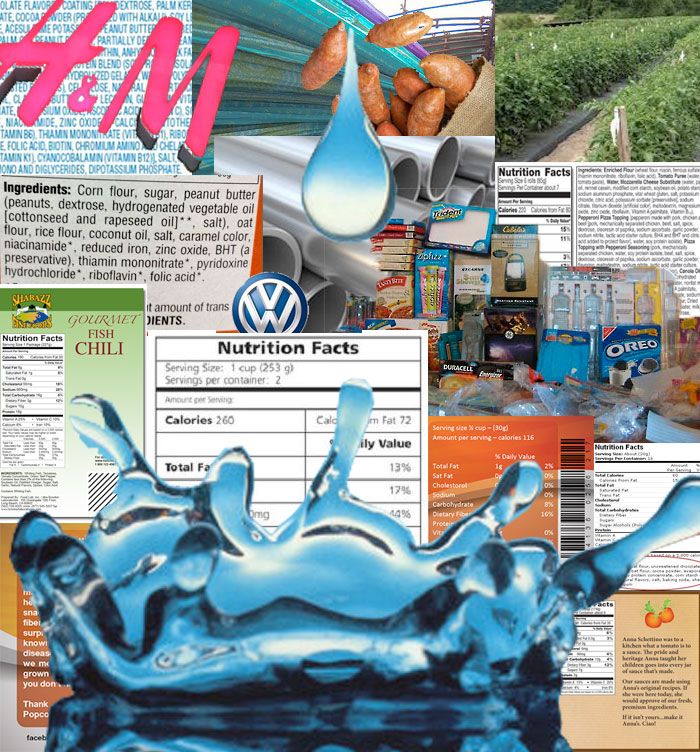

I use as one example the image of walking down a supermarket aisle and hearing a torrent of cascading water in untold volume used for the processing, packaging, and distribution of the products found on the shelves.

Water is a fundamental externality in the financing of production, rarely calculated into the price in that it is often free or heavily subsidized for the manufacturer and incidental to specific accounting for the specific product. Thus, the true cost of the most important resource, not just to the making of one item or another, but to the overall availability of the water consumed to the larger needs of society – drinking water, sanitation, irrigation, and much, much more – is left out of the financial equation.

To provide an example, I recently took from the shelf a paper package of Imagine Natural Creations tomato bisque soup. It was covered with notifications, certifications, nutritional information, labels, and pronouncements.

Indeed, Imagine Natural Creations declares an exhausting awareness and purposeful dedication to the health of its consumers, to the highest quality of the purest ingredients, and to the thoughtful packaging for the future of the world forest ecosystem. And, as added value, the tomato bisque tasted just fine.

But what was missing from all this information? How much water was used in the growing of those tomatoes, pulp, and paste? How much water was used in the processing and the making?

But what was missing from all this information? How much water was used in the growing of those tomatoes, pulp, and paste? How much water was used in the processing and the making?

How was the water waste from production treated and disposed of? Where did the water come from and was its availability subsidized by the costs of public treatment and distribution?

Do any of the certifications cited include water use in the criteria applied? How much water was used in the production of the packaging, the distribution of the product, the continuous progress from raw ingredient to point of sale?

The point here is that the most important component remains hidden, an unarticulated value, positive and negative, that might enter our calculation of its desirability for consumption. Would it not be as useful to know a rating of water use against that of a competitor as much as the use of salt?

If we are concerned about GMO ingredients and demand such labeling from our legislators as a public responsibility, why should we not be equally concerned about water consumption labeling with equal and immediate impact on our individual and public health?

Would it not be a constructive project for one of our water-directed institutes concerned with critical water availability and use around the world to define the principles and criteria for such an evaluation and move for voluntary, even legislative adoption of such information to be listed not just on food products but on every product and its packaging, from smart phones to computers to automobiles, from metal, paper and wood products, iron, steel, and aluminum, from fracking for oil to the cooling of nuclear generators and our houses and offices, from the growing of all things eaten from meat to vegetables and from all beverages imbibed from beer to soda to coffee to, yes, even organic soups? Truth in labelling.

It’s time for us to know and publicly declare how the circles and cycles of water work on our consummate behalf and how we must protect and recycle that essential value as the key ingredient in our future sustenance. Let’s certify water!

Media

Taxonomy

- Water

- Conservation

- Sustainability

- Water Monitoring

- Consumption

- Conservation

- Labeling

3 Comments

-

I totally agree. We have included water footprint calculations based on different food basket calculations in our recently published Urban Water Atlas for Europe at the city level for about 40 cities. Clear: we all have to reduce meat consumption. Here is the linkedin post for your information where the beautiful Atlas can be downloded for free:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/urban-water-atlas-europe-kees-van-leeuwen

-

I totally agree but feel the water label is a good idea...complex...the Chlorine Free Products Association uses third party auditing of pulp and paper mills... measures water and water quality ...as the standards we are using creates a SI (Sustainability Index)...be glad to share more and searching for partners in Asia, India, n Africa

-

It is a great concept but a very complex one. You can account for the water you take under your license or the volumes service provider delivers. But accounting for how much went into what is time consuming, expensive and complex for any industry or individuals.