Water Reuse At Oil Drilling Sites May Reduce Fracking-Induced Earthquakes

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Academic

A University of Texas at Austin study has found that reusing the large amounts of water rising to the surface at oil exploration sites is not only efficient, but a way to potentially reduce the chances of inducing earthquakes from horizontal drilling activity.

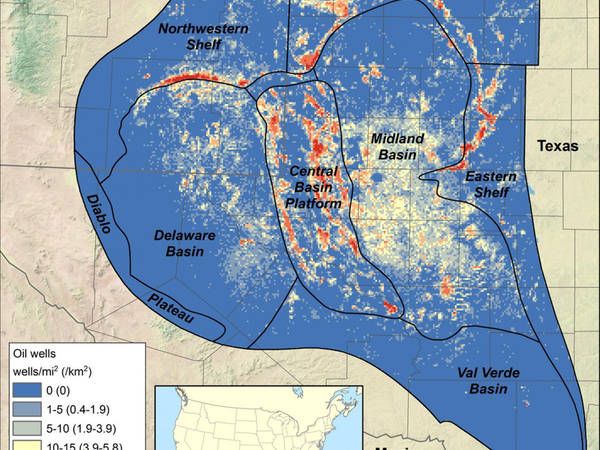

The university's study centered on the Permian Basin, an expansive oil field sprawled over large swaths of land in Texas and New Mexico. The focus also was on hydraulic fracturing—a practice more commonly known as "fracking"—that involves drilling down to search for oil but then proceeding in a horizontal fashion beneath the earth's surface, cracking through rock and sediment to get to oil pockets in crevices otherwise not able to be extracted via conventional drilling techniques.

But at fracking becomes more widely practiced, the incidence of man-made earthquakes heightens. The UT Bureau of Economic Geology led the study highlighting key differences in water use between conventional drill sites and sites that use hydraulic fracturing rapidly expanding in use in the Permian Basin.

The study was published in Environmental Science & Technology with results indicating that recycling water produced during operations at other hydraulic fracturing sites could help reduce potential problems associated with the technology, university officials said. Among the drawbacks studies were the need for large upfront water use and potentially induced seismicity or earthquakes, triggered by injecting the water produced during operations back into the ground.

To give an idea of the horizontal drilling success: The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that the Permian’s Wolfcamp Shale alone could hold 20 billion barrels of oil, the largest unconventional resource ever evaluated by the agency.

As part of the UT-Austin study on the amounts of water at the drilling site, a decade's worth of water data from 2005 to 2015 was examined. The researchers tracked how much water was produced and how it was managed from conventional and unconventional wells, comparing those volumes with water use for hydraulic fracturing.

Not surprisingly, hydraulic drilling was found to use exponentially more water than conventional vertical drilling. The average volume of water needed per well, the study found, has increased by about 10 times during the past decade, with a median value of 250,000 barrels or 10 million gallons of water used per well in the Midland Basin in 2015. Yet unconventional wells produce much less water than conventional wells do, averaging about three barrels of water per barrel of oil versus 13 barrels of water per barrel of oil from conventional wells.

In conventional operations, produced water is disposed of by injecting it into depleted conventional reservoirs, a process that maintains pressure in the reservoir and can help bring up additional oil through enhanced oil recovery, officials noted. Unconventional wells generate only about a tenth of the water produced by conventional wells, but this “produced water” can't be injected into the shale formations given the low permeability of the shales, the study found.

Further findings showed that the produced water from unconventional wells is largely injected into non-oil-producing geologic formations—a practice that can increase pressure and could potentially result in drilling-induced earthquakes.

To mitigate such seismicity, UT-Austin scientists pointed out that rather than injecting the produced water into these formations, operators could potentially reuse the water from unconventional wells to hydraulically fracture the next set of wells. Enough water is produced in the Midland and Delaware basins in the Permian to support hydraulic fracturing water use, and the water needs only minimal treatment (clean brine) to make it suitable for reuse, scientists found.

Source: Downtown Austin Patch

Media

Taxonomy

- Oil & Gas

- Research

- Groundwater

- Reuse

- Brackish Water

- Fracking

- Produced Water From Oil & Gas Industry

- Hydraulic Engineering