Lessons From Leonardo: What Leonardo da Vinci Can Teach Us About Water

Published on by Jim Lauria, VP Sales & Marketing at Mazzei Injector Company, LLC in Academic

Lessons From Leonardo: What Leonardo da Vinci Can Teach Us About Water

Salvator Mundi sold for nearly half a billion dollars. Walter Isaacson’s latest biography is a breakaway hit. Management guru Michael Gelb’s book accessing the thought techniques of history’s most accomplished Renaissance Man—in every literal and figurative sense of the word—is still a bestseller. Almost 500 years after his death, Leonardo da Vinci is still a superstar.

From his first painting of the bucholic Arno River to his final deluge drawings, most of his paintings featured water. (That included the Mona Lisa , which scholars believe portrays the Trebbia River in the background—a detail almost as mysterious as subject Lisa Gherardini’s famously cryptic smile.)

In addition to his spectacular paintings, his remarkable inventions (from conceptualizations of submarines to SCUBA gear) and his studies as a scientist, anatomist and mechanical genius, Leonardo was also the Nostrodamus of the water industry, a man who saw into the future. Much of what he envisioned could serve us well today. After five centuries, Leonardo da Vinci has plenty of lessons for us on water.

Understand the Science of Water

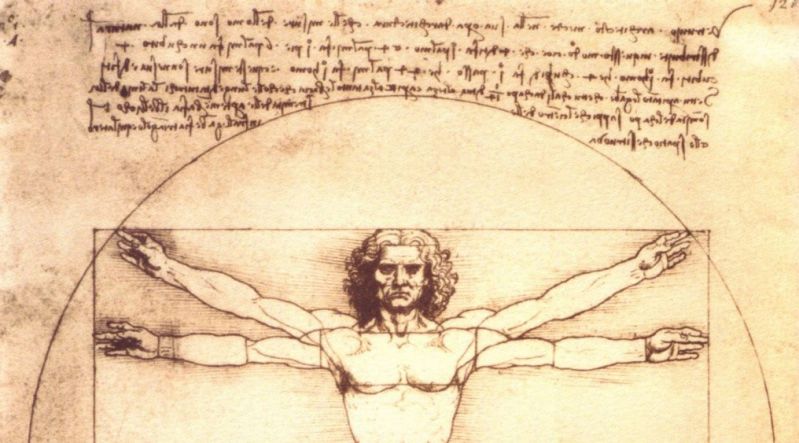

We can take a page from Leonardo’s relentless curiosity to understand the science of water. After all, 72 pages of the Codex Leicsester , a compilation of Leonardo’s writings, focus primarily on the earth and its waters—730 conclusions about water alone. Leonardo was fascinated by water, observing the fact that unlike air, it cannot be compressed, or that flowing water constantly undergoes perfect geometric transformations. He recognized the relationship between flow speed and pressure in water, principles that underlie airplane wings and venturi injectors. (In turn, the inventor of the venturi tube, Giovanni Venturi, turned the world’s attention to Leonardo as a scientist—not just an artist—in 1797.)

Leonardo was fascinated by the properties of water at both the micro and macro level, and accurately described the hydrological cycle—the endless loop of evaporation, condensation and precipitation that binds our global water supply. Five hundred years later, the hydrological cycle helps us understand the impacts of climate change and comprehend a future of deeper droughts, flashier storms and changes in the distribution of the world’s water.

We may never understand what Lisa Gherardini was smiling about when Leonardo painted her in the Mona Lisa , but we really need to understand the hydrological cycle and the science of water.

Take a Systems Approach

The hydrological cycle wasn’t Leonardo’s only big-picture, systemic view of water.

Leonardo famously alternated between sketching human anatomy and mechanical systems. He’d start on musculature, tendons and bones and end up drawing pulleys and levers. His descriptions of cities were downright anatomical, too, with water flowing through arteries and cities breathing and excreting.

That’s a lesson that applies a hundred-fold today, now that we have sensor eyes and ears, computer brains and state-of-the-art filtration systems that act like kidneys and livers.

When we combine the analogy of the human body with the concept of the hydrological cycle, we can begin to see that water can play a wide range of functions, be treated to more than one level, and vary in its value and function. We can start to figure out how to get beyond thinking of water as some monolithic commodity and start to consider how to optimize the use of potable water, brackish water, process water, flowing water, gray water, wastewater…and cycle it all back again.

Infrastructure Matters

Leonardo re-imagined post-plague Milan as a set of ten towns spread along the city’s canals, its residential areas separated from industry and its waste streams, reducing crowding and minimizing the buildup of “fetid smells…pestilence and death.” It’s an elegant model of urban design, and it applies now more than ever in our era of overcrowded cities and intensive use of resources.

Those designs presaged today’s growing awareness of the importance of decentralized water treatment. And in cities that (still) sit atop Roman-era plumbing, Leonardo saw the need to update and upgrade. With our nation’s much newer systems, we’re still facing a desperate need for infrastructure maintenance and improvement. Let’s learn from Leonardo and not wait for a plague or disaster to prompt creative thinking about our infrastructure.

Harness the Power of Water

As an unparalleled engineer (civil, mechanical and hydrological), Leonardo understood the yin-yang relationship of water and energy. It inspired him to propose the application of water power for useful purposes, from water-driven sawmills to forges, flour mills, factories and silk spinning works.

And though he was a peace-loving, vegetarian hippie dude well before his time, he wasn’t averse to putting water to work for military uses. He weaponized water.

With his buddy Niccolo Machiavelli, Leonardo drafted a plan for strangling the rival city-state of Pisa by diverting the Arno River. Leonardo’s diversion canal probably would have worked—not only did he engineer the diversion, but he designed earth-moving equipment and conducted a detailed operations engineering analysis of the job—but the contractor took shortcuts and doomed the effort.

When we look at the world, we need to see water in its strategic sense, the way China does, or our own Department of Defense, which deeply studies water and climate change to spot emerging conflict zones and assess potential locations for operations. (DOD also uses its water processing capabilities as an instrument of peace and diplomacy, which is why the U.S. Navy is often an early responder to natural disasters around the world, its water treatment systems pumping out vital potable water for stricken populations.)

Invest in Study

Leonardo was proud to be a self-taught man. But he wasn’t one of those bright guys we all knew in school who insisted they never studied. Leonardo studied and he studied hard .

Leonardo was the kind of scientist who didn’t just measure every bone in the human body. He did it for horses, too. He wrote a list of 67 words that described moving water. He was a detail guy, a devotee centuries before his time of the dictum that grew from Lord Kelvin’s dogma: “You can’t manage what you don’t measure.” That’s a drive we should all nurture in ourselves.

What’s more, Leonardo studied for the sake of knowledge even at the cost of painting commissions that would have paid him a handsome living. Leonardo appreciated the beauty, fame and paycheck that came from creating masterpieces like The Last Supper or the Mona Lisa —but he also valued the knowledge that came from his explorations, his experiments, his dissections and his reading.

Pass Along Knowledge

Despite the phrase “self-taught,” Leonardo sought out experts and tapped their knowledge. We need to do that, too.

We need to tap into the experience of our colleagues, the tribal knowledge that exists in the water community. We need to learn from the operators who know where every valve and dead leg is. We must connect with the experts who have witnessed—and led—the revolution in today’s water technology.

Leonardo was a prolific recorder of his thoughts and findings, leaving behind dozens of journals that reflect a vital commitment—to share insight. In the water industry, we need to not only gather information, but share it. As professionals, we need to provide perspective to the public on pressing water issues, and share insight among ourselves on the latest science and practices.

Write articles, blog, speak at conferences. Gather knowledge and pass it along.

Pay Heed

There’s something deep and antique in the phrase “pay heed” that makes it perfect for emphasizing the importance of Leonardo’s lessons. We need to pay heed to the messages he has passed down in his journals—the importance of water and the respect for its power. We must pay heed to Leonardo’s model of experiential learning, his hunt for experts who could shed light on the secrets of anatomy or biology, and his relentless curiosity. And we need to pay heed to the example he set to be multi-dimensional thinkers, pulling together the threads that link the world’s systems, whether it’s cities with beating hearts and flowing arteries or water that can be harnessed to spin silk or defeat a rival city.

As much as I love Italian wine, today I raise a glass of pure water to Leonardo, whose favorite image, management guru and Leonardo fan Michael Gelb tells us, was the rippling of water when a stone was dropped in. May his ripples continue to emanate throughout the world.

Media

Taxonomy

- Water

- Technology

- Research

- Infrastructure

- Hydrology