How Irrigation Development Modifies Local Climate

Published on by Berend van der Zwaan, Hydrologist at Eelerwoude in Academic

With approximately 70% of all freshwater consumption worldwide used for agriculture, the reliance on large-scale irrigation development continues to spread in many regions.

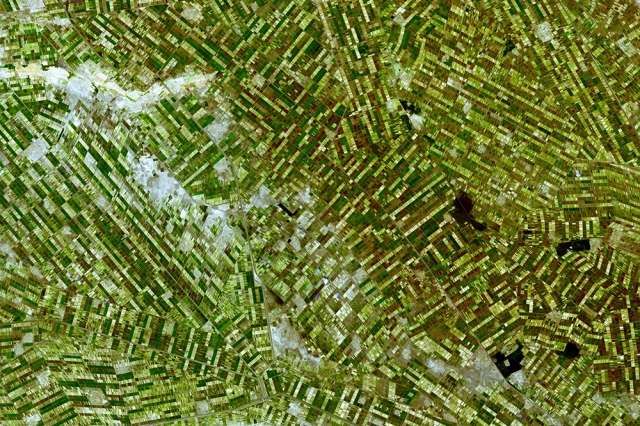

A satellite image shows irrigated fields (green and brown), irrigation canals (gray lines between fields), and villages (grey-white patches) within the Gezira Scheme in Sudan. Credit: NASA

But the ongoing expansion of cropland irrigation, just as with any human-made land-cover change, holds potential for unintended consequences. The consequences of such human activity should be well understood before being implemented.

In a paper, an MIT team in the department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE) investigates the impacts of large-scale cropland irrigation on rainfall patterns in the East African Sahel around the Gezira Irrigation Scheme, now considered one of the largest irrigation projects in the world.

The researchers piloted their exploration by combining theoretical modeling analyses with observational evidence gathered over several decades since 1930—an unprecedented approach in previous studies.

The CEE team studied 60 years' worth of data of rainfall, temperature, and river flow to empirically deduce the atmospheric impacts of irrigation development.

"Large-scale development of irrigation systems is a good example of human activity that has changed land cover and the environment significantly in many regions of the world," says co-author Professor Elfatih Eltahir, associate department head of CEE. "In all development projects, we need to better understand the potential impacts of our actions on the environment before we mindlessly develop."

According to the theory developed by the researchers based on their investigation, when a large area is irrigated, surface air temperature is cooled and surface pressure increased. This reaction was conjectured to reduce rainfall over the irrigated land while generating a clockwise circulation that interacts with the prevailing regional wind.

Depending on that interaction, the theory predicts that specific areas of convergence would be created, which would boost the rainfall in some of the surrounding areas.

After the researchers concluded their deep analysis of regional climate data, they concurred that large-scale irrigation development in the East African Sahel has consistently enhanced rainfall in areas to the east of the irrigated lands, while reducing rainfall directly over them.

Spatially and over time, the changes in rainfall and temperature matched up in a way that exceeded the group's expectations and almost perfectly aligned with the original theory, says co-first author of the paper and CEE postdoc Ross Alter.

"You don't often achieve that type of clear-cut match when attributing regional climate change from both theory and observations," Alter says.

The team's findings, says Eltahir, are indicative of the need for further consideration of potential agricultural, hydrological, and economic repercussions from irrigation expansion.

Read more at: Phys.org

Media

Taxonomy

- Agriculture

- Irrigation

- Freshwater

- Consumption

- Irrigation Management

- Irrigation Scheduling

- Agriculture

- Environmental Impact

- Farms

2 Comments

-

The hypothesis of the Paris Agreement on the emission of carbon dioxide leads to disaster because it distracts the world from the real threat of all life on the planet. The main root of climate change is the change in evaporation. Vapors - the main link in the chain of water cycle between the atmosphere and soil. In the pre-industrial era, organic evaporation from biota prevailed. Now, with the acceleration, artificial evaporation of water, devoid of its natural functions, is fueled by feeding flora and fauna.

Adaptation to climate change means humility of mankind with natural disasters and an approaching catastrophe. The person will adapt to the conditions today, and tomorrow the conditions will worsen even further and a moment will come when no trillions will suffice for survival. First, the poorest layers, and then the whole of humanity. -

would there be any difference between and irrigated forest with healthy top soil and open irrigated crop area's. I guess evapo-transpiration and sub-soil water balance will be very different. In other words; would a comparison with a forest and an irrigated open agricultural area be interesting to compare? has this been done?

1 Comment reply

-

I think the differences between forest and agricultural area will be very large. Some forests are known to create their own micro-climate, living (partly) on their own transpiration. Also take into account that agricultural area is harvested every year or even more frequent, so that the soil is bare for a couple of months. I would have to dive into my study material to find out what the effects will be, but I think it is very interesting to find out!

A recent study in Canada showed that when forest is cut (or in the case of the study, killed by beetles) the groundwater replenishment decreased due to more evaporation, caused by more sunlight, higher temperatures and more wind.

-