10 critical steps for Ganga revival

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Government

As PM Modi advises states along the river to shift focus from Namami to Arth Ganga, it is clear that the Ganga cannot be restored by only pollution-abatement measures

![]() The Ganga. Photo: Flickr

The Ganga. Photo: Flickr

The Himalayas are the source of three major Indian rivers namely the Indus, the Ganga and the Brahmaputra. Flowing for about 2,525 kilometres (km), the Ganga is the longest river in India. The Ganga basin constitutes 26 per cent of the country’s land mass and supports 43 per cent of India’s population.

The government of India has set up an empowered body consisting of a dedicated team of officers as part of the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) under the Union Ministry of Jal Shakti (earlier called as Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation).

The NMCG has stated its vision in terms of four restoration pillars, namely Aviral Dhara (continuous flow), Nirmal Dhara (clean water), Geologic Entity (protection of geological features) and Ecological Entity (protection of aquatic biodiversity). According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB)'s 2014 estimates, approximately 8,250 million litres per day (MLD) of wastewater is generated from towns in the Ganga basin, while treatment facilities exist only for 3,500 MLD and roughly 2,550 MLD of this wastewater is discharged directly into the Ganga.

Namami Gange has completed 114 projects and about 150 projects are in progress, while about 40 projects are under tendering, of which 51 sewage projects were approved before May 13, 2015 — the day Namami Gange was approved by the Union Cabinet.

Till April 2019, 1,930 MLD of sewerage treatment capacity in 97 Ganga towns has been developed, whereas the sewerage generation in these towns is 2,953 MLD. It is further projected that the sewerage generation would touch 3,700 MLD by 2035.

The industrial pollutants largely originate from tanneries in Kanpur, paper mills, distilleries and sugar mills in the Yamuna, Ramganga, Hindon and Kali river catchments. Then, there is the huge load of municipal sewage which contributes two-thirds of total pollution load.

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) in November 2019 had imposed a penalty of Rs 10 crore on the Uttar Pradesh (UP) government for failing to check sewage discharge containing toxic chromium into the Ganga at Rania and Rakhi Mandi in Kanpur. It also imposed a penalty of Rs 280 crore on 22 tanneries for causing pollution.

The cost of the damage was assessed by the state pollution control board (UPPCB) as compensation for restoration of environment and the public health in the area. Incidentally, the NGT also held UPPCB liable and directed it to pay Rs one crore for ignoring illegal discharge of sewage and other effluents containing toxic chromium directly into the Ganga.

The NGT, in its order dated December 6, 2019, directed local bodies and concerned departments to ensure 100 per cent treatment of sewage entering rivers across the country by March 31, 2020. In the case of non-compliance, the NGT has warned authorities that they will be liable to pay Rs five lakh per month per drain falling in the Ganga and Rs five lakh for default commencement of setting up sewage treatment plants.

Water in India is a state subject and water management is not a truly knowledge-based practice. The management of the Ganga lacked basin-wide integration and is not very cohesive between various riparian states. Further, there is a greater challenge of upgrading the water supply and wastewater treatment infrastructure in the designated smart cities and of providing clean water supply to all rural households by 2024 under the Jal Jeevan Mission.

Given the limited water resources, the task is enormous. For about three decades, the different strategies to clean-up the Ganga were attempted such as the Ganga Action Plan (GAP, Phase I and II) and establishment of the National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA). But no appreciable results were achieved.

Recently, the Ganga Council headed by Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi, in its first meeting held on December 14, 2019, floated a plan to promote sustainable agriculture in the Gangetic plain by promoting organic clusters in a five-km stretch on both sides of the Ganga basin in Uttarakhand, UP, Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal.

It is a good policy move, considering the cumulative use of pesticides has doubled in the last one decade and most of it runs off in our rivers. For the short-term, the five-km stretch is fine, but the government should eventually plan to stretch it to cover more area in the basin. Agriculture along the entire riverbed should be organic.

Media

Taxonomy

- River Studies

- River Engineering

- River Restoration

- River Engineering

3 Comments

-

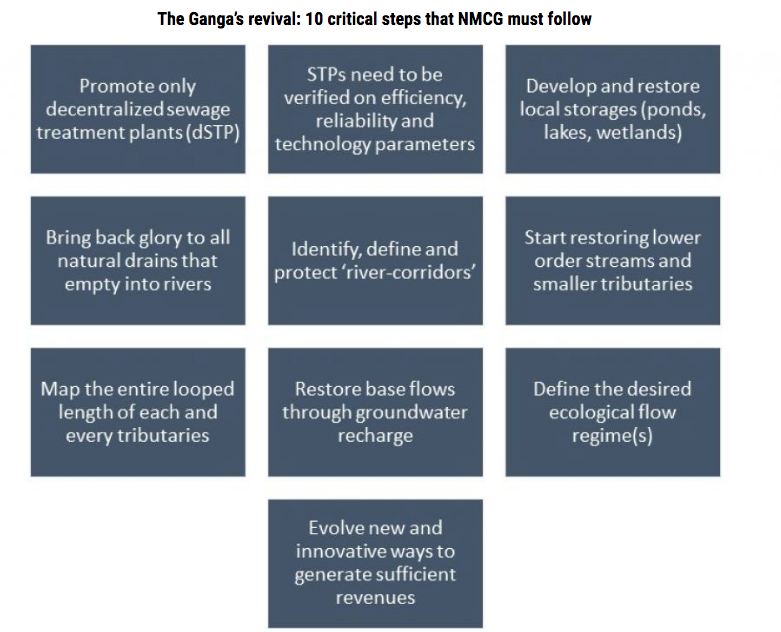

The ten critical steps to be followed by NMCG are commendable. I have a few comments to bring focus to what must not be forgotten or overlooked. These are stated below:

1. The decentralised sewage treatment systems should have the twin objectives of reuse and recycling of treated sewage and community management of the facility. Flushing toilets, landscaping and use for cooling condensers of centralised air-conditioning systems are some important ways to utilise treated sewage.

2. Reliability of sewage treatment plants should include uninterrupted power supply and storage of untreated or partially treated sewage for ensuring that no sewage reaches a water body without adequate treatment.

3. 'Bring back glory to drains' sounds good but does not clearly convey that storm water drains must be dry during dry weather.

4. Attention to lower order streams and small tributaries should be according to cost-effectiveness in improving the health of main river, Ganga.

5. Ecological flow needs to be ensured rather than just defined.

6. All innovative ways to generate revenue must be critically examined for their impact on the river and for the socio-economic aspects with respect to equity.

-

На моей странице есть решение этой проблемы: в статье 3рабсРусс.docx

-

It is very sad to note that even Centre Govt. has failed to address the issues for rejuvenation of the Holy River in last six years and now there seems to be a shift in focus altogether. NMCG had paid attention to foreign entities and did not trust the knowledge and talent available locally and did not attempt a doable action plan when it had no dearth of funding. Even now, India can attempt any ambitious project with or without foreign support but planning has to be much better addressing the critical issues in their totality and whatever powers are with the Legislature should get utilised to enact any laws, create a balance between responsibility and authority of NMCG to plan and execute the project in the planned time. River Rejuvenation project requires Multi-disciplinary specialists fully devoted to the cause, working effectively with the powers vested in them as a team. Even NGT or its nominee and CPCB together with representatives of state PCB can also be made a part of that team and the total work plan to be worked out should be NMCG's responsibility under Ministry of WR &NG and it should have nothing to do with the state till the project is completed and the Ganges as a rejuvenated resource is handed back to the states. Rather than seizing the opportunity, having utilised precious time of last 6 years, it is shifting the responsibility by changing the narration of the problem. Do we assume that politically, GOI has now a diminished interest in even attempting what is required to be done to rejuvenate the holy river. If this be so, even the future of River Interlinking projects seems to be bleak!