In Conversation with Angus Webb, one of the Editors of Water for the Environment

Published on by Water Network Research, Official research team of The Water Network in Academic

The Water Network team had the pleasure to interview Angus Webb, one of the editors of the book Water for the Environment: From Policy and Science to Implementation and Management.

Angus Webb is a quantitative ecologist in the Environmental Hydrology and Water Resources group within the Department of Infrastructure Engineering, University of Melbourne.

His research focuses on the study of landscape-scale impacts of human-induced disturbances on freshwater systems, and what can be done to restore these systems.

Quantitative ecology is the use of maths and statistics to try to make sense of our natural environment, or to try to make predictions about individuals, populations or ecosystems.

Currently, we spend a lot of money collecting data, but not getting maximal value from this investment. Through more advanced analytical approaches, we can often gain additional insight into these complex environments.

Q1. Thank you for taking the time to talk to us Angus. Would you please start by introducing yourself and telling us about your professional background?

Q1. Thank you for taking the time to talk to us Angus. Would you please start by introducing yourself and telling us about your professional background?

I’m a part of the Environmental Hydrology and Water Resources group within the Department of Infrastructure Engineering at the University of Melbourne.

Three of the editors of the book, Avril Horne, Mike Stewardson and myself, are from this group. We partnered with Brian Richter from the Nature Conservancy in the US, and Mike Acreman from the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology in the UK, to develop the book.

Most of my research should be described as quantitative ecology, which means using mathematical and statistical modelling to make sense of large data sets in river systems. I undertook my PhD in marine ecology, before moving into the study of freshwater systems, and in particular human impacts on them at Monash University, also in Melbourne.

Q2. “Water for the Environment: From Policy and Science to Implementation and Management” is the first book to try to tackle all elements of the environmental water lifecycle. Why did you structure the book that way and what is the importance of integrated water management?

The equitable use of water for human consumption and for the environment is one of society’s ‘wicked problems’ – that means there’s no solution where everyone can be happy.

So providing water for the environment is not just about using science to work out how much water is needed by the organisms in a river; we also need policy experts and lawyers who can provide the legislative frameworks to allow this; we need social researchers who can understand the impacts on human societies of returning water to the environment; we need economists who can understand how the value of water changes through different climate cycles and regulatory frameworks; and finally we need engineers and infrastructure specialists who can actually make the flows happen.

Integrated management is only really possible if you’re considering all these things at once. There were quite a few books around already on environmental water, but they were specialized texts that only tackled one of these areas at a time. We thought that there was a real need for a book that took a high-level approach to all areas within the environmental water management landscape.

Q3. Who is the book meant for and how can it help in applying the multidisciplinary environmental water management from theory to practice?

We think the book will be of most use to river and catchment managers who are attempting to implement environmental flows. We think it will help with multidisciplinary water management because it provides a broad view of all the areas, and enough information for somebody to then go further into the literature if they need to.

We also think that the book will be useful for students in the diverse disciplines that contribute to environmental water management, by providing them with an indication of just how many different disciplines need to come together to implement and manage effective environmental water programs.

Q4. What is the best approach to achieve circular economy in water management? Is holistic approach the solution and how can we best implement it?

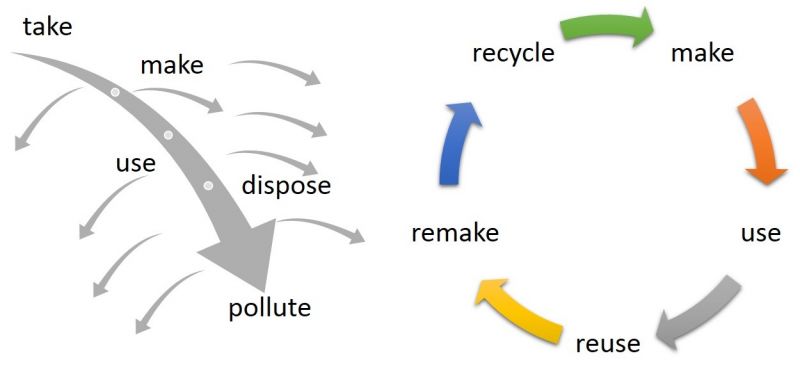

I don’t think that a circular economy model is the best way to think about water. Outside of approaches such as water reclamation and recycling, we’re generally not trying to use water over and over again. Good water management, both for human consumption and the environment, is really about being very efficient with the resource.

There is never enough water to satisfy everybody’s requirements, and so we need to get much better at using it efficiently. There have been some spectacular gains in efficiency in irrigation in the last 10 years of so, with farmers able to produce much more produce per litre of water. This is what we’re also seeking to do with environmental water, by monitoring outcomes and continuously learning how to use water better.

Image: Linear versus Circular Economy

Q5. What are the limits of water conservation?

There must be a limit, but I don’t think we really have much idea what it is yet. For many years, the design of environmental flow programs has been dominated by the idea of the ‘natural flow regime’ – when we deliver environmental water, we try to include the natural variation in flow rates and high and low flow periods. This has been very successful, but more recently we’ve seen the introduction of the newer concept of ‘designer flows’, which means we deliver a specifically engineered flow regime that is designed to do better than natural. In water constrained environments, this type of approach is proving very successful as we learn more and more about how these environments operate.

Q6. How does the history of environmental water management teach us and help us in today’s water management?

We need to remember that environmental water management is still a very young field. The paper on the natural flow regime is 20 years old, and in that time we’ve gone from knowing very little about how to deliver environmental water, to now being in a better state of knowledge where we have a reasonable idea of what will happen.

We need to remember that environmental water management is still a very young field. The paper on the natural flow regime is 20 years old, and in that time we’ve gone from knowing very little about how to deliver environmental water, to now being in a better state of knowledge where we have a reasonable idea of what will happen.

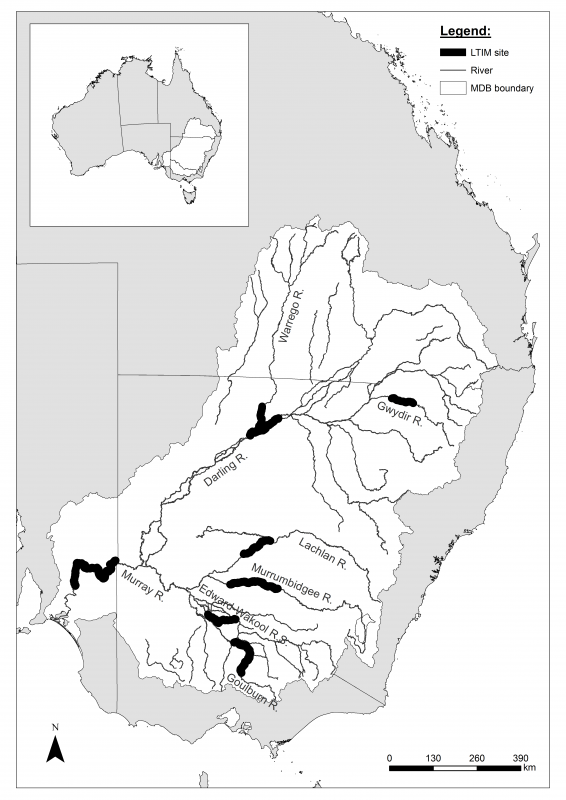

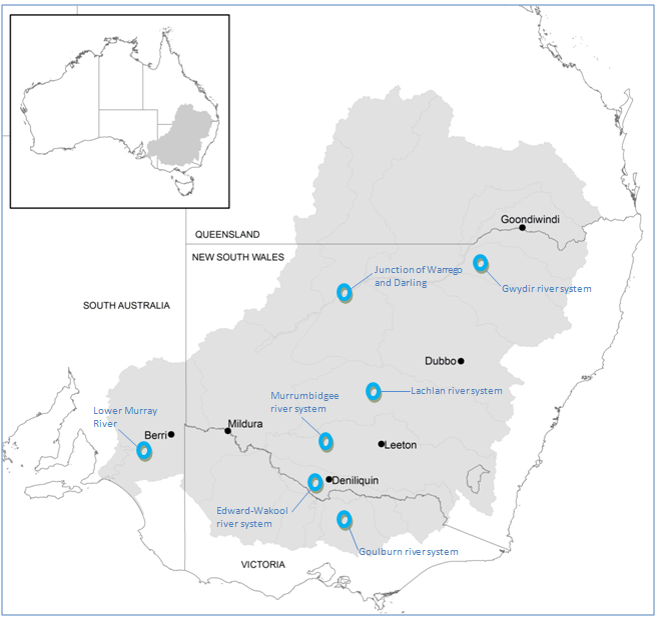

Actual implementation of environmental water programs around the world has lagged a long way behind the science and policy, and these programs are only now starting to become more common. In Australia, the Murray-Darling Basin Plan has the largest environment water program ever attempted. We’re trying to return about 20% of the water that was being used for irrigation back to the environment, and we’re doing that over the scale of the entire Murray-Darling Basin, which is about 15% of the area of Australia.

With the roll-out of programs like the Basin Plan, the rate at which we’re learning how to do environmental water management is increasing rapidly. But everything has built off the early science and smaller-scale programs as well.

Q7. Is technology advanced enough to implement the fully integrated water management? Should the focus be on data collection integration and leadership, rather than technology?

I think it’s about striking the balance – about using tried and true approaches where we know they will work, but also being innovative in the way we monitor responses to environmental water, and indeed design environmental water programs. Much of the monitoring that we do for environmental water is done using approaches, such as fish electrofishing, that have changed very little in decades.

There’s really good potential for using some of the latest approaches, such as remote sensing through drones, to greatly increase the amount of data that we can collect. But developing new methods is a research question, which needs to run alongside monitoring programs.

In some of our research here at Melbourne University, we’re using mathematical optimization to try to help inform release decisions for environmental water. Using this sort of approach we can design flows that get the most bang for buck. But this is still very much a research project, and we’re a few years away from seeing it used in water management. But it’s not all about technology either, participation in environmental water management by local communities, as well as managers and scientists, is essential if they are to be successful long term.

Q8. How can we best overcome the fragmentation of the urban water cycle?

If we were better able to harvest the water that is currently falling on our cities as stormwater, then we’d have a great deal of the supply problem solved. We have huge amounts of infrastructure that currently efficiently channels urban stormwater into streams and away from cities, doing quite a lot of ecological damage in the process.

If a substantial portion of that water can be captured and used for human purposes, not necessarily drinking, but other uses, then this would take the strain off drinking water supplies. This is one of the principles behind Water Sensitive Urban Design, which is being seen to a greater and greater extent in cities in the developed world, especially in new developments.

Q9. Could you please tell us a bit about the water reform process in Australia and what is driving it? What can we learn from it?

Southern Australian experienced a drought from 1997 to 2010 that became known as the Millennium Drought. Although the environmental end economic damage of the drought was huge, we actually got through it better than many would have expected.

When California started to experience drought in recent years, there was a rush to try to find out what had happened in Australia to buffer us against the worst effects of the drought. However, the answer really began several years before the drought started, when the federal government moved to change the way water was owned and could be used, and recognized that a sustainable agricultural sector was only possible if it was occurring within a sustainable environment.

The really major things that happened were that water rights were de-coupled from property rights. That meant a land owner could now sell water to somebody prepared to pay more for it. Second, users began to actually pay for the cost of maintaining the water infrastructure. Prior to that, it was heavily subsidized by the government. This made water more expensive. These two things meant that farmers started using water much more efficiently in agriculture, and we were able to increase production with the same amount of water. It was some time after that that environmental water started to become more prominent, but it faces the same restrictions as agricultural water; it has to be paid for and it has to be managed.

The main lesson that we can take away from this is that it wasn’t rapid actions during the drought that saved Australian agriculture and environments, although these were important too. It was the longer-term decisions, made outside of the panic of the drought, which created the environment within which decision makers could respond.

Q10. How exactly is water sustainability measured?

That’s a tough one. In Australia, we had a lot of very clever people work for a long time to come up with our ‘sustainable diversion limits’, which are estimates of how much water might be removed from different systems without causing irreparable environmental damage. This process employed hydrologists, ecologists and other specialists to try to see when environments would tip into a new and undesirable state. The process employed a lot of data and modelling, but also the accumulated expertise of specialists who had been working in Australian rivers for decades. But we need to remember that these are estimates, and we’re now seeing to what extent those will be proved correct.

Q11. What are some of the best response strategies in water management?

One thing that we’re starting to do quite well is induce native fish reproduction. There is a small number of species that will only spawn with the right flow conditions, and we’re now getting quite good at creating these. In the Goulburn River, in Victoria, where I work, the golden perch is an iconic native species. We’ve been delivering high flow pulses in late spring, once the water gets warm enough. These cause the fish to move downstream in the river and to reproduce there. We can be quite targeted with the flow events. They really only have to go for a few days. The key is making sure that the water is warm enough when the flows are delivered. This is one nice example.

Q12. How does adaptive management of environmental flows change and develop with practice?

I’ve spoken a few times already about learning from practice, and this is the essence of adaptive management. We have to make decisions in these systems; making no decision is not an option. But we’re often making decisions with little knowledge. By conducting good monitoring and evaluation, we can learn about what does and does not work, and use this knowledge to improve management decisions in future.

Again, in my project in the Goulburn River, we have a very close partnership between the researchers and the water managers. This means that what we learn from monitoring gets fed back very quickly into decision making in that system. The example I talked about before, with golden perch spawning, is one where we’ve learned how to do this over the course of several, often frustrating, years. But we now feel that we’ve got that problem pretty well sorted out.

Q13. What are the major challenges for the future of environmental water management?

We actually investigated this as part of the last chapter of the book. We ran a survey and a workshop to do what’s known as a horizon scanning exercise, and came up with several major areas and distinct questions within these areas. The detailed questions are published in a paper that has just come out in Frontiers in Environmental Science, again with Avril Horne as lead author. There are too many things to describe in detail, but one that particularly resonates for me is that, for the most part, environmental flows have been implemented and managed in developed countries. For those systems, it was a case of undoing the damaging of too much water regulation in decades gone by.

The question is how can we implement environmental flows in developing countries, so as hopefully to avoid that type of damage in the first place; to put sustainable water development in place? It’s a considerable challenge because the legislative and regulatory environments aren’t as well developed, and we usually have much less basic knowledge about the hydrology and the ecology of the systems that need to be managed. If we can crack environmental flows in developing countries, then we will have come a very long way.

Q14. What are the most important long-term water policy issues?

I’m probably a bit biased here, because I’ve seen how well it worked in Australia, but creating the legislative frameworks to allow for water markets is very important. As I described earlier, this was one of the important factors for getting us through the millennium drought.

Very few countries have functioning water markets. Water is often still tied to land ownership, and systems like ‘prior appropriation’, which literally means that the person with the oldest water right always gets their water, no matter how little is in the system, really act against improving the efficiency of water use for both human and environmental purposes.

Q15. Where can people get your book?

The book is available on line through major retailers like Amazon and Google books, and also directly from the Elsevier by searching for the title. There’s also an advertisement on the Water Networks products showcase. I’ve set up a shortened URL, which is www.tinyurl.com/WaterForTheEnvironment to take you directly to the book’s page. It’s available in either hard copy or electronic form. If you’ve got a particular interest, then individual chapters are available through Elsevier’s ScienceDirect platform too.

Read More Interviews from the 'In Conversation With' Series

by The Water Network

Attached link

http://www.youtube.com/embed/0RGOZxksPEQMedia

Taxonomy

- Policy

- Resource Management

- Environmental Policy

- Water Resource Management

- Hydrology

- Governance & Policy

- Integrated Water Management

- Environment

- Sustainable Water Resource Management

- Natural Resource Management

- Environment Evaluation

- Hydrology

- Environmental

- environmental management

- Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM)